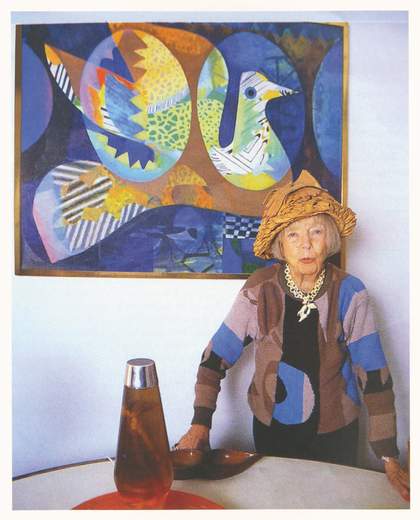

Eileen Agar wearing her Glove Hat 1936 and standing by her painting The Bird’s Nest 1969 at her home in London, 1989

© The estate of Eileen Agar. All Rights Reserved 2020 / Bridgeman Images. Photo: John Glynn

Eileen first properly entered my life when she was widowed. She was then in her late 70s; I was in my early teens. Fiercely independent, and with a wide-ranging collection of friends, she conceded that Sunday lunch with her remaining family might be amusing. In complete contrast to my beloved grandmother, who had neatly permed hair and grey, tweedy outfits, Eileen would appear at the door in a relative dazzle of colour, pattern, stripes and polka dots, with her Cleopatra bob and electric-blue eye shadow. In she would step, with her retractable walking stick wielded like a magician’s wand. I thought she was marvellous.

She would tell tales of her extraordinary life, holidaying in the South of France with Picasso, rescuing Dalí from asphyxiating himself when he was trying to give a speech in a metal diving suit at the opening of the International Surrealist Exhibition in London in 1936, and dismissing Evelyn Waugh’s attempt to seduce her. I particularly remember her relaying with great glee, in that slow, drawly way she had of speaking, the time that Herbert Read and Roland Penrose turned up at her studio.They were scouting out new artworks for the International Surrealist Exhibition and they said, ‘Oh, but you’re a surrealist!’ As she reached the punchline her eyebrows would shoot up and, with a mischievous grin, she would repeat her reply from those 40-something years ago: ‘Am I?’

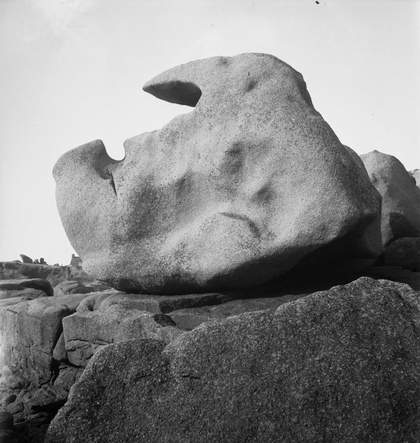

Her flat was like an eclectic gallery space, brimming with colour and texture. Its high, white walls were covered from floor to ceiling with hundreds of her paintings, as well as some by her contemporaries – Henry Moore, Paul Nash, Lee Miller. There were intriguing objects too – some harvested from her beachcombing days and used to create surprising sea sculptures, embracing shell couples, painted stone and bone creatures. There was even a curlicue of iron railing, recovered from her blitzed London house, whose shape reappeared, rippling into one of her brightly coloured paintings.

Each time I went, everything would have moved, like musical chairs, rearranged and changed with other objects from her storage room. It was like a game, working out what had been replaced, and she relished discussing her reinventions. But it was her sense of colour, her mischievous humour and her joyful patterning that excited me the most. Although she claimed to ‘love all colours’, I loved the persistent sky-water malachite/blue that flowed through so much of her work, as if a memory of her long sea voyages to and from Argentina, where she spent her childhood.

Eileen was tiny. I recall her in her 80s, sitting in her studio like a fragile bird of paradise, dressed in brightly patterned clothes – frequently designed by herself – and engulfed in a huge red-andwhite-striped armchair. In front of her was a table on which were piled magazines and journals, and all sorts of bric-à-brac, which, Matisse like, she used to cut up and, with an enviable selection of coloured pens, pencils and felt tips, use to make her collages.

I used to ask about her collages – which she continued to make right up into her 90s – and her replies were always enigmatic. For her, the process was always intuitive, as if the pieces had formed themselves.

Like Eileen, I too left home to live and paint abroad in my early 20s. She was very supportive of my move to India as I, following in her pioneering footsteps, was stepping into the unknown to let chance and the unexpected lead my life. I would like to think that she’s left a lasting influence, as I too am obsessed with colour, patterning and shapes from nature. Eileen had no children of her own, but she left an enduring impression on me as someone who transformed the greyness of the world around her into something brightly coloured, startling and mysterious. As she frequently used to say: ‘Room must always be made for joy in this world.’

Nineteen sculptures by Eileen Agar are held in Tate Archive. A selection of these are on loan to Whitechapel Gallery, London for Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy, coming soon.

Olivia Fraser is an artist based in London and Delhi.