Auguste Rodin

The Tragic Muse, small model 1890

Plaster 31.5 × 68 × 37.7 cm

© Musée Rodin – photo Christian Baraja

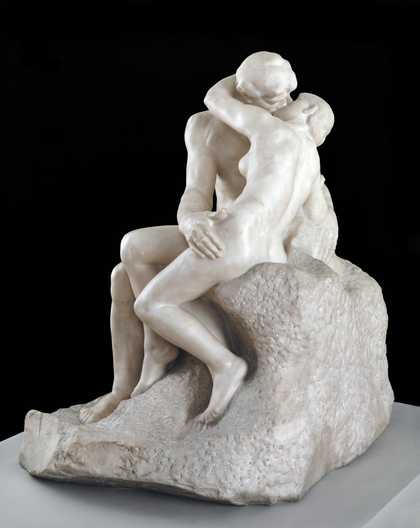

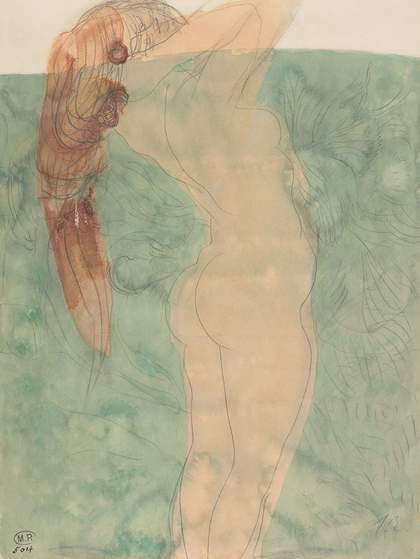

To many, Auguste Rodin’s works appeared direct and expressive, with dramatic gouges, marks, and finger impressions littering his surfaces. His preference was for sculpting nude bodies, often freed from any identifying story or mythology. Viewers could marvel at the traces of making he left on his works, and the sculptor’s touch in the clay was often taken for the lover’s touching of the nude – despite the missing limbs, contortions, or imprints of fingers and hands on Rodin’s sculptural bodies. Under his hand, sculpture was understood to have become more sensual, and the evidence of his manipulations of matter reinforced the frankness that viewers saw in the unclothed bodies writhing in passion, shame, or heartbreak. The popularity of Rodin’s work rested on this elision of the sexual and the material; and his contribution to modern sculpture was to make it more physical, more palpable, and a closer record of the frenzied scene of creation – or at least that is what his supporters would have us believe.

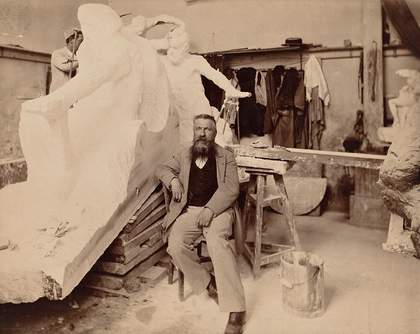

Rodin placing the plaster Clenched Hand with Imploring Figure on a pedestal, in the Pavillon de l’Alma, Meudon, 1906

© Musée Rodin

These marks, however, are by no means direct or unmediated. We need to recall that most basic of conditions for the interpretation of nineteenth-century sculpture: the initial object created (the clay sculpture) is often lost. The sculpted clay is used to create the mould into which bronze or plaster will be poured; bronze sculptures are the result of the transposition of the form from a clay sculpture to the negative space of the mould, and then to the bronze. This is a specialised procedure involving a foundry and its specialists – in other words, a bronze sculpture is the product of many hands. While still once removed from the sculpted clay, plaster was privileged by Rodin in this process, as it allowed opportunities for him to replicate and recombine his sculptures into new compositions and configurations. Other sculptors considered plaster merely an intermediary material on the way to bronze or marble, but Rodin chose to defiantly exhibit his plasters in 1900 as exemplary of his sculptural practice and the central role of his hand in it.

Auguste Rodin Assemblage: Female nude standing combing her hair with Head of the Sphinx and seated Female nude holding her left foot c.1900–10

Plaster and plaster slip 28 × 17.5 × 18 cm

© Agence photographique du Musée Rodin – Pauline Hisbacq

Rodin’s reputation, however, was based on bronze casts, and many associate him with this material. Despite what appears to be evidence of personal handling by Rodin, the objects we call his are – like most nineteenth-century sculptures – rarely the direct product of his hands, even though the enduring image of Rodin is physically present, touching each object in a way that is visible and recoverable on the surface of the sculpture. Roger Marx, for instance, spoke of Rodin’s caress of the modelling clay, even though the art critic and his readers would only ever have seen bronze, marble, or plaster: ‘under [Rodin’s] fingers the clay quivers with feverish throbs, and trembles with every spasm of suffering and anguish.’ This focus on Rodin’s hands and evidence of his touch was made central by Rainer Maria Rilke, who began his book on Rodin by discussing them: ‘Instinctively one looks for the two hands from which this world has come forth.’

Auguste Rodin Assemblage: Female torso with the head of Woman with a Bun and head of Pierre de Wissant, reduction after 1895

Plaster 24.2 × 17.6 × 13.5 cm

© Musée Rodin – photo Christian Baraja

Decades later, John Berger remarked in his perceptive essay that, in all Rodin’s figures, ‘one feels that the figure is still the malleable creature, unemancipated, of the sculptor’s moulding hand. This hand fascinated Rodin.’ What interests me here is the discrepancy between this perception of Rodin’s hands metaphorically hovering near the works – that is, his simulated presence – and the deferred materiality of the medium of nineteenth-century sculpture.

‘Expressiveness and not finish is [Rodin’s] ideal’, wrote the painter Louis Weinberg in an essay written just after the sculptor’s death. Indeed, Rodin’s handling and sculptural style were intended to produce a set of specific effects. Instead of the even, often glassy surfaces of much previous nineteenth-century sculpture, Rodin kept the rough with the smooth, leaving areas seemingly unfinished, with the marks of the chisel or the thumb still in them. Unworked areas of clay remained on the works, standing in for bodily surfaces.

Rodin with the plaster Monument to Victor Hugo in the studio of the Dépôt des Marbres, Paris, c.1898, photographed by Paul Marsan, known as Dornac

© Musée Rodin

Such strategies were not unique in the history of sculpture. Michelangelo, for one, had been a catalyst for Rodin’s development of his own version of the non-finito. However, for Rodin it was not just an arrested realisation of the sculpture but a tactical stylistic choice, repeated across the various modes and materials of his sculpture. In addition, he exaggerated the occasional use of approximated details and sketchy surfaces that other nineteenth-century sculptors would sometimes use. For Rodin’s immediate predecessors and peers, however, these tactics were largely limited to works that were either selfconsciously preparatory sketches or modellos, or (as in the case of painter and sculptor Honoré Daumier) as an equivalent to the hyperbolic drawing style used in caricature. Rodin drew upon such precedents but pushed their tactics further. He incorporated them into finished works intended to be cast or carved, and he realised that the approximated and abbreviated details could be read as more active and less fixed than seamless verisimilitude.

He built into his process and exhibition practices the appearance of unfinish, of spontaneity, of his touch, as a means of bringing his works the vitality that he viewed as lacking in the academic style. Increasingly, most of his mature sculptures by the late 1880s begin to look as if they are somehow in process – as if they bear fresh evidence of his physical acts of art-making.

Again, this was not a casual or careless move on Rodin’s part; it was strategic. He staged these traces of his touch as more emphatic and deliberate so that they would survive the translation from clay to other materials. It is common for many viewers and critics to think of the marks of process on these works as if they were self-evidently indexical of Rodin’s presence. As the French journalist Gustave Geffroy put it, ‘The sculptor’s intention, moreover, is visible in every creation of his hand’ with ‘the mingled passion and gentleness that informs his modelling, the caressing tenderness that tempers his virile strength.’ Although these marks appear to be traces of Rodin’s actual, physical manipulation of the material, they simulate his direct and unmediated touch in defiance of the actual material history of the sculptural object as the product of teams of makers and multiple materials. This is an obvious point that is nevertheless often forgotten or overlooked when viewers and critics encounter a sculpture such as Rodin’s. But by recognising their anxious relation to the multi-staged practice of sculpture, it becomes clear that Rodin’s practice as a whole relies upon a different, and more infectious, function for these marks – as performative, rather than just constative or descriptive, of Rodin’s presence.

Auguste Rodin Ugolino and His Children (for The Gates of Hell) 1882

Plaster 41.5 × 41.5 × 62.5 cm

© Musée Rodin – photo Adam Rzepka

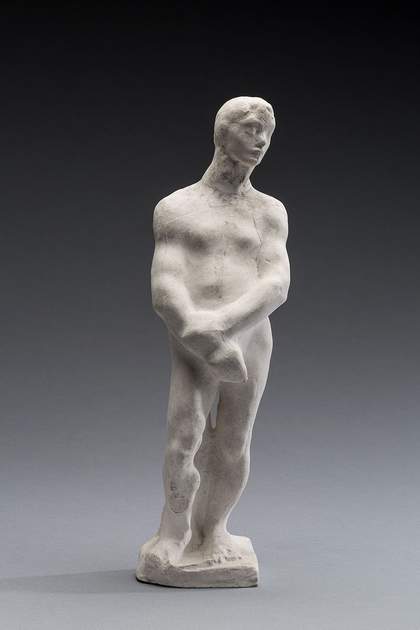

In making this claim, I am contending that Rodin’s over-dramatic facture was more than just a performance of bravura handling in defiance of naturalism – it was akin to a performative utterance that declared Rodin’s appearance as the primary meaning of the work. Rodin’s marks are transformative. His activated surface traces relied upon the deployment and propagation of replicable and transmissible signs that, once recognised as such, transform the condition of the sculptural figure to foreground both its objectness and Rodin’s share in the formation of that object. When the viewer’s experience of the statue becomes interrupted by these marks that are recognised as not having to do with the sculptural image – be it a representation of a woman, a man, a couple, a thinker – they shift emphasis to the sculptural thing itself as the product and registration of Rodin.

All sculptures operate between image and object, between representation and materiality, but Rodin’s intervention into the discourse of nineteenth-century sculptural praxis was to sacrifice verisimilitude, representational consistency, and the coherence of the figure itself in order to let his acts of making overtake the object, even after the form had undergone material transcriptions and been the product of other hands. While the plasters are closer to the clay in this chain of sculptural transmutation, we should remember that the plasters are reproductions of the lost clay objects with their fossilised fingerprints and marks of process.

Auguste Rodin Assemblage of reduced heads of Jean d’Aire and Jean de Fiennes and hands, topped by a winged figure after 1899

Plaster 24 × 28 × 23.5 cm

© Agence photographique du Musée Rodin – Pauline Hisbacq

Rodin deployed signs of his presence that would survive the translations of a sculpture across materials but always point back to the fact that the object was made by him and that this scene of creation was the object’s primary source of significance for the viewer. Whereas paintings, for instance, might exhibit facture or display materiality, sculpture under Rodin’s hands mobilised facture so that it would subvert the multi-staged material vicissitudes of the sculptural form, allowing each (and every) sculpture to appear to have arisen directly from his touch. He developed an equivalent mode of production to the heightened facture that had become an increasingly attractive option in painting at the end of the nineteenth century but did so within a medium that relied strongly upon lost ‘originals’ and their multiple reproductions. In short, his effective transmuting of the sculptural object produced by other hands is different from the facture we associate with Rodin’s painter-contemporaries’ staging of directness in their unique hand-made art objects.

Auguste Rodin Female nude in profile with loose hair c.1895–1910

Graphite and watercolour on paper 32.2 × 24 cm

© Musée Rodin – photo Jean de Calan

The literature on Rodin, from the late nineteenth century onwards, has largely accepted as an open secret the factitious status of Rodin’s performative marks (especially in his bronzes). His friends and later advocates and historians all wrote with awareness of this issue. The goal is not to expose the open secret but rather to argue that the uncritical acceptance of it obscures the more fundamental art-theoretical move made by Rodin’s performative marks and transmuting effects. The significance of these marks is not that they are mediated but rather that they capitalise on their own mediation and allow Rodin to overtake depiction and subject matter in making his art and, on the level of technique and making, to point back to his (mythical) acts of making the objects that bear these traces.

Ultimately, what I am arguing is that Rodin’s contribution to modern sculpture was not just the seeds of abstraction, which is how his fragmentation of the body and fractured surfaces have often been interpreted. Subsequent sculptors did interpret this as a stylistic attitude toward verisimilitude, but Rodin’s strategy was more complex. It involved redirecting the viewer’s attention from image to object as the site at which his hand would be most visible. The point is not that the marks are mediated or ‘fake’ but, rather, that their emphatic overlay on the sculptural object – across its material transcriptions – creates a shift in what we look for in the sculptures.

Auguste Rodin Male Nude Standing with the Head of Slavic Woman before 1906

Plaster 29.5 × 9.2 × 7 cm

© Agence photographique du Musée Rodin – Jérome Manoukian

This is the basis of Rodin’s ‘liberation’ of sculpture and what has been called the demise of the tradition of the statue. Simply put, after Rodin, we increasingly have sculptures, not statues – that is, objects, not images. Rodin’s performative marks strategically masquerade as direct traces in order to convince the viewer that this untouched object has been touched by him. The false immediacy of these marks does not mitigate the fascination they inspire in viewers. This is because they effect the more insidious result of keeping the artist near; Rodin’s presence becomes semantically fused with these objects because of the ways in which they short-circuit the distinction between sculptural representation and materiality – between object and image – that nineteenth-century sculpture had relied upon. This shift from sculptural image to sculptural object is, on the one hand, a fundamental contribution to twentieth-century discourses of modernism, and, on the other, the precondition for Rodin turning his own acts of making into the denominator of meaning. The performative mark not only says that ‘Rodin was here’ but also declares that the sculptural object is important primarily because of that claim.

The EY Exhibition: The Making of Rodin is presented in the Eyal Ofer Galleries, Tate Modern, 18 May – 21 November. Curated by Nabila Abdel Nabi, Curator International Art, Tate Modern, Chloé Ariot, Curator for Sculpture, Musée Rodin, Paris, Achim Borchardt-Hume, Director of Exhibitions and Programmes and Helen O’Malley, Assistant Curator, Tate Modern. The exhibition is part of The EY Tate Arts Partnership. With additional support from the Rodin Exhibition Supporters Circle and Tate Patrons. Organised by Tate Modern and Musée Rodin, Paris.

David J. Getsy is the Goldabelle McComb Finn Distinguished Professor of Art History at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His books include Abstract Bodies: Sixties Sculpture in the Expanded Field of Gender (2015) and Queer Behavior: Scott Burton and Performance Art (forthcoming, 2022). This article is based on a chapter in his book Rodin: Sex and the Making of Modern Sculpture (Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2010).