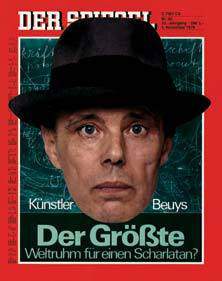

Joseph Beuys plants the first tree for his artwork 7000 Oaks in front of the Fridericianum Museum, Kassel, Germany, 1982

© DACS 2021. Photo © Günter Beer, Barcelona / beerfoto.com

Beuys planted an oak tree alongside a column of volcanic basalt rock in Kassel, Germany. It was the first of 7,000 treeand- stone couplings introduced to the city over five years under the auspices of the art exhibition Documenta 7, seeding a self-perpetuating cycle of trees growing and dropping acorns. Beuys had coined the term ‘social sculpture’ – art that related to people’s everyday lives and activities to transform society. At the time, the climate crisis loomed on the horizon and Beuys declared that planting trees was ‘necessary not only in biospheric terms’ but also for its role in raising ‘ecological consciousness … in the course of years to come, because we shall never stop planting.’

For Beuys, art possessed a transformative capacity, acting on materials and people’s thoughts and actions. 7000 Oaks was the manifestation of his desire to reforest all cities, an early instance of the rewilding now common in metropolises around the globe. Although the biodiverse work comprised some 16 different tree species, it was the oak that had the most potent symbolism, representing ancestral knowledge and mythology; the tree revered by druids as a site for rituals and gathering mistletoe. The slow growth of oaks chimed with the ancient basalt columns with which they were paired, inviting awareness of deep, geological time, in stark contrast to the span of a human life.

Since the early 1980s, 7000 Oaks has engendered an ecology of wildlife and meaning stretching through Kassel and beyond. In 2007, British artists Ackroyd & Harvey collected around 600 acorns from Beuys’s trees, planting them in pots. While their project is based in the UK, the saplings have since toured around France, coinciding with the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) in Paris. Today, there is a micro-forest of around 150 second-generation trees, 100 of which will be stationed this spring outside Tate Modern to celebrate the centenary of Beuys’s birth, while Beuys’s installation of 31 basalt rocks The End of the Twentieth Century 1983–5 will be displayed in the Tanks. Since the early 1990s, Ackroyd & Harvey’s works have initiated cycles of organic growth and decay as a way to broach issues of climate change and renewal. In 2019 they co-founded Culture Declares Emergency, a pressure group campaigning for climate awareness and ecological action with over 1,500 individual and institutional signatories, including Tate.

Shuvinai Ashoona Composition (People, Animals, and the World Holding Hands) 2007–8 Ink and coloured pencil on paper 66 × 102 cm

Courtesy the artist and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid

Beuys, who co-founded the German Green Party, understood that culture and climate are inextricably linked to politics. He believed that marrying ancient knowledge and tradition with radical political action could pave the way to a sustainable future. The full title of his work, 7000 Oaks: City Forestation Instead of City Administration, alludes to a dichotomy that underpins our climate emergency: between nature as a sacred space of growth and a rationalised commodity to be administered. Today, the conflict between these two worldviews plays out most urgently in parts of the planet inhabited by indigenous peoples.

At a recent British Museum event for the exhibition Arctic: Culture and Climate, Maatalii Okalik, an Inuk from Nunavut, in the Canadian Arctic, and President of the National Inuit Youth Council, made the point succinctly: ‘indigenous people are the human barometers of climate change’. Their lands also have the greatest biodiversity, indicating that their ways of life may offer solutions to a sustainable relationship between humans and the planet. These time-honoured attitudes, which include acting as custodians for future generations under the watchful eyes of ancestors and embracing kinship with plants and animals, are strikingly up to date. As Okalik stressed, ‘traditional Inuit actions are climate actions. We are raised to think how our actions impact the generations to come.’ Yet indigenous knowledge is in peril, from centuries of oppression, erasure and genocide. Indigenous peoples are systematically excluded from national and international decision-making: they will attend this year’s UN COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, but as observers, not as parties.

Beuys’s trees endure from one generation to the next, because the genetic blueprint for each mature oak is encoded within a tiny acorn. In a similar way, the keys to the survival of our species, which depends on our response to the climate crisis, exist in the wisdom and practices of indigenous cultures. Art can help us recognise the assets and solutions we humans hold, and to envision ways forward. Unfortunately, art alone cannot enact the global transformation we now need to protect indigenous peoples, lands and knowledge, and to ensure the survival of our species. As Beuys knew, in order to achieve this, art must be coupled with radical political will and action.

Ackroyd & Harvey’s Beuys’ Acorns is currently on display on the South Terrace at Tate Modern. Joseph Beuys’s The End of the Twentieth Century is on display in the East Tank at Tate Modern until October.

Ellen Mara De Wachter is a writer and yoga teacher living in London. Her book Co-Art: Artists on Creative Collaboration is published by Phaidon.