Sophie Taeuber-Arp in costume for a housewarming party organised by artist Walter Helbig, Ascona, Switzerland, August 1925

Fondation Arp, Clamart, France

On 20 March 1917, an unknown photographer took a portrait of a 27-year-old woman. Her face is hidden by a large, rectangular mask comprised of huge cubist eyes, a nose like an alp and a ferocious mouth, topped with a crown as jagged as a saw. Her arms, raised as if to fend off blows, are encased in robot-like tubes; her gyrating body, which appears to jerk like a giant marionette, is draped in a patterned fabric that looks at once ancient and futuristic. Although more than a century old, the image crackles with energy. Inside the costume is its creator, the Swiss artist, designer, dancer, puppeteer and architect, Sophie Taeuber; she is performing a series of ‘abstract dances’ to the dadaist Hugo Ball’s cycle of phonetic poems at the opening of the Galerie Dada at Bahnhofstrasse 19 in Zurich. Ball described the spectacle in his diary:

A poetic sequence of sounds was enough to make each of the individual word particles produce the strangest visible effect on the hundred-jointed body of the dancer. From Song of the Flying Fish and the Sea Horses there came a dance full of flashes and edges, full of dazzling light and penetrating intensity.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp performing to the sound poem by Hugo Ball in costume and mask probably by Jean (Hans) Arp on the occasion of the opening of the Galerie Dada, Zurich, March 1917

Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin

Taeuber and the Alsatian artist Hans (later known as Jean) Arp – who probably designed her mask and was to become her husband in 1922 – were part of a like-minded young group of artists, writers, poets and performers from across Europe who sought refuge from the First World War in Switzerland. When, in 1916, the poet and puppeteer Emmy Hennings and the artist, poet and musician Hugo Ball rented a small room in a wine bar and called it Cabaret Voltaire, the headquarters of dada came into being: a theatre of absurdist protest at the government-sanctioned carnage that had been raging across the continent since 1914, resulting in the deaths of around 38 million people. At a time of mass murder, the dadaists celebrated individuality: they weren’t interested in an idealised version of life and espoused an artform in which no single medium dominated. They believed that convention – a mindset that had given the world permission to go to hell – was something that not only art but everyday life should be purged of. Restless, despairing, provocative and yet often wildly funny, their improvised art, poems and performances reflected human experience in all of its messy, irrational glory. This portrait of Sophie Taeuber – who was to become one of the most important European artists of the first half of the 20th century – is only one of three surviving photographs taken of the irreverent soirées that rocked the quiet Swiss city to its foundations, and which, in so doing, changed the course of modern art: it leapt from the canvas and onto the stage.

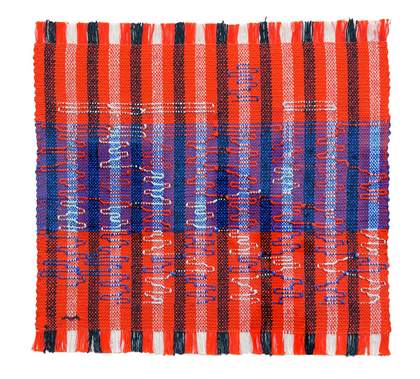

Sophie Taeuber-Arp Cushion Panel 1916

Wool on canvas 53 × 52 cm

Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin. Photo: Alex Delfanne

Sophie Taueber’s journey from bourgeois respectability to the Galerie Dada was swift. Born on 19 January 1889 in Davos to a middle-class family, her father died when she was two. Her mother, an amateur artist, encouraged her daughter’s creativity. Between 1911 and 1913, Taeuber was enrolled in an experimental art workshop in Munich; she later moved to Zurich to study textile design and modern dance. (Hugo Ball described her as ‘a bird, a young lark … lifting the sky as it took flight.’) By 1916, she had a routine: by day, she made and occasionally exhibited her paintings and drawings; taught embroidery, weaving and textile design at the School of Applied Arts; and studied at Rudolf von Laban’s international school of dance. She also attended some of the earliest meetings of the Zurich Psychology Club. By night, she performed in dada extravaganzas under a pseudonym. Arp described how:

She danced a goldfish losing all its gold and swimming poor and miserable away.

She danced darkness, evil growing bored with itself and wanting to turn into its opposite but unable to decide whether it should become a child or an angel.

She danced questions, too.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp Geometric Forms (necklace) c.1918

Glass beads, metal beads, thread and cord 33.5 cm long

Museum für Gestaltung, Zürcher. Hochschule der Künste, Private collection Zurich. Decorative Arts Collection

She also painted geometric compositions – a melding of vertical and horizontal lines, rectangles and triangles in colours that sang – designed necklaces, bags, clothes, lamps, textiles, costumes and marionettes, and created sculptural portraits (including one of Hans) from turned wooden hat stands she titled Dada Heads.

In 1915, she had met Hans at a group exhibition, Modern Wall Hangings. Embroidery. Paintings. Drawings, in which his work was included, at Tanner Gallery in Zurich: they soon became entwined, emotionally and artistically. Recalling their life together between 1916 and 1918, when they collaborated on works such as the ‘Duo-Collages’, Hans wrote that:

The clear tranquillity of Sophie Taeuber’s vertical and horizontal compositions influenced the diagonal, baroque dynamics of my abstract creations … Sophie Taeuber and I resolved never to use oil colours again. We wanted to discard any reminder of oil painting, which seemed to us to belong to an arrogant, pretentious world. During the years that we abstained from oil painting, we used in our works exclusively paper, cloth, embroidery, as spiritual exercises, as a discipline that allowed us to recapture painting in its original purity.

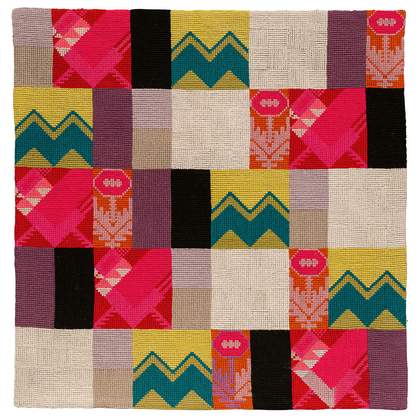

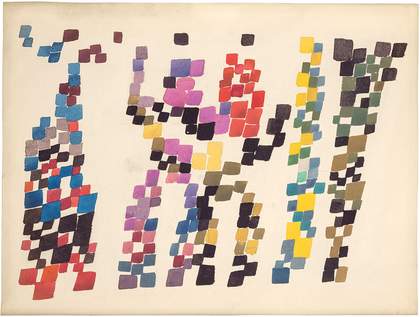

Sophie Taeuber-Arp Quadrangular Strokes Evoking Group of Figures 1920

Gouache and graphite on paper 26.5 × 35 cm

Seroussi Collection, Paris

Despite the trauma of two world wars, Taeuber- Arp’s approach to art-making was essentially joyful: she took inspiration where she could and then explored its creative possibilities, indifferent to traditional hierarchies of art and craft. Her paintings throb with rhythm, her dancing echoed sculptures, a collage might become a rug or a watercolour inspire a bedspread. Although a pioneer of abstraction, her use of geometry is never rigid: straight lines waver and bright primary colours jostle for attention. Inspired by nature, much of her work, even at its most abstract, alludes to the expanse of the sky, the swell of the sea and the curve of the earth. ‘In a flower,’ she wrote, ‘in a beetle, every line, every form, every colour has arisen from a deep necessity.’

Sophie Taeuber-Arp Equilibrium 1932

Oil paint on canvas 41.7 × 33.5 cm

Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin. Photo: Alex Delfanne

Throughout her too-short life, Taeuber-Arp lived, breathed and inhabited art: it was a source of solace, a symbol of possibility, a space of improvisation. A description of her teaching method by one of her students, Elsi Giauque, is revealing. She explained:

Her lessons were all about strange materials and impractical stuff. We would have to make something from these by the following morning. There was no apparent programme, no real clue as to what she was expecting or hoping for – we were left to fend for ourselves. Independently, we were supposed to discover, invent and create something that no one else had ever come up with before.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp in the planning office for the Aubette, Strasbourg, France, 1927

Fondation Arp, Clamart, France

In 1926, the architect Paul Horn and his brother André commissioned Taeuber-Arp, who had been working on various interior design projects, to decorate and furnish the east wing of the Aubette, a cultural centre in the main square of Strasbourg. She invited her husband and the Dutch De Stijl artist Theo van Doesburg to join her. Taeuber-Arp took on the Five O’Clock tearoom, two bars and the billiard room. The result was one of the first public interiors to integrate modernist ideas of art and function. The dadaist Emmy Hennings described the experience of visiting the Aubette:

The walls, covered with paintings, give the illusion of almost endlessly vast rooms. Here painting makes the visitor dream, it awakens the depths in us. The house may become a treasure box, a reliquary, and one can always look at it with new eyes … It is like owning the lamp with which Aladdin lighted the marvellous cave.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp Relief 1936

Oil paint on wood and plywood 55 × 65 × 16.2 cm

Emanuel Hoffmann Foundation, on permanent loan to the Öffentliche Kunst Sammlung Basel. Photo: Kunstmuseum Basel / Hanz Hinz

The proceeds from the Aubette helped the Arps move to Meudon on the outskirts of Paris, where Sophie designed their modernist stone home, studio and furniture. Their lives were rich with experimentation, exhibitions and friendship with artists including Sonia and Robert Delaunay, Marcel Duchamp, Wassily Kandinsky and Joan Miró. Taeuber-Arp’s versatility was evident in the international exhibitions her work was included in: both those dedicated to abstract or concrete art as well as surrealism. But alongside her painting and designs, in 1937, Taeuber-Arp founded and edited the trilingual art magazine Plastique: its first issue was dedicated to the Russian suprematist Kazimir Malevich. (It lasted only five issues: the Second World War put an end to it.) Taeuber-Arp also became a member of the abstract artist groups Cercle et Carré (Circle and Square), Allianz – a union of Swiss painters – and Abstraction-Création. But this glorious period of community and artistic experimentation was threatened – alongside everything else – by the rise of Nazism. In 1935, at the party conference in Nuremberg, Adolf Hitler had railed against ‘the Dadaist-Cubist and Futurist gasbags of life and objectivity’ and their ‘cultural stuttering’.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp Construction of a Black Circle and Burgundy, Red and Blue Segments 1942

Ink, gouache and graphite on paper 35.2 × 27.2 cm

Arp Museum Bahnhof Rolandseck, Remagen. Photo: Mick Vincenz

With the advent of the Second World War and the German occupation of Paris, in 1940 the Arps fled from Paris via Peggy Guggenheim’s villa overlooking Lake Annecy to Grasse, where they stayed with the artist Alberto Magnelli and his wife Susi Gerson; they then rented a house of their own and Sonia Delaunay came to stay after the death of her husband Robert Delaunay. For Taeuber-Arp, it was a time of prolific art-making: she made more than 100 drawings over the next two years. The horror of a new global conflict brought about a sombre shift in her approach: her high-key palette was replaced by more monochromatic, even earthy tones. The circle had become her favoured shape: a metaphor that alludes to unity, infinity, the cosmos. Whereas her earlier work had been titled along purely descriptive lines, now, paintings such as 1942’s Lost Lines on Chaotic Background expressed her anxiety. Arp remembered:

We lived between a well, a graveyard, an echo and a bell … From her purity she drew the courage and confidence to endure the immense misfortune of France. From the depths of the most intense suffering, blossoming spheres shoot forth. Lost and impassioned, she drew lines, long curves, spirals, circles, roads that twist through dream and reality.

In 1942, Hans and Sophie came back to Zurich. In 1943, Sophie died of accidental carbon monoxide poisoning at the home of their friend, the artist Max Bill. She was 53. Hans was inconsolable. Remembering their early years together, he wrote that: ‘We humbly tried to approach the pure radiance of reality. I would like to call these works the art of silence … We wanted to simplify and transmute the world and make it beautiful’.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Tate Modern, 15 July – 17 October. Curated by Natalia Sidlina, Curator, International Art, Tate Modern, Anne Umland, The Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller Senior Curator of Painting and Sculpture, The Museum of Modern Art, Walburga Krupp, Independent Curator, and Eva Reifert, Curator, Kunstmuseum Basel with Sarah Allen and Amy Emmerson Martin, Assistant Curators, Tate Modern. Supported by John J. Studzinski CBE, with additional support from the Sophie Taeuber-Arp Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate Patrons and Tate Members. Organised by Tate Modern, The Museum of Modern Art, New York and Kunstmuseum Basel.

Jennifer Higgie is Editor-at-Large of Frieze magazine. Her book on historic women’s self-portraits, The Mirror and the Palette, is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson.