Paula Rego in her studio in London, 2019

Photo by Linda Brownlee / Contour by Getty Images

In The Heroine’s Journey (1990), Maureen Murdock writes that if the central image of Western religion were that of a woman giving birth, rather than a man dying on the cross, then the impetus in our culture would rest on life and the love of life, rather than death and the fear of death. Over email, during the third London lockdown, I ask Paula Rego if she agrees with this statement? ‘That’s interesting,’ she replies. ‘In Portugal many of us pray to the Virgin Mary. I’m not trying to express a love of life or a fear of death – those things may come through because they are in me. I hope the pictures have life.’

Paula Rego

The Family 1988

Acrylic paint on paper on canvas

213.4 × 213.4 cm

Rego, now 86, is preparing for her major retrospective at Tate Britain in the summer. Her narrative works in paint and pastel, drawn from models and props in her Camden studio, often show women in scenes of murderous compliance. The Policeman’s Daughter 1987, for example, is a large-scale acrylic painting of a girl with her fist thrust deep into her father’s black boot as she polishes it for him. The Family 1988 is another large-scale acrylic painting which shows daughters possibly dressing or undressing their ailing father in a way that violates him. There is comedy in the violation, which is particular to Rego. Her style is dreamily realist, even illustrative, but her subject matter is that of a psyche made dark by censorship. She has the gift of transforming the oppressive circumstances in which she finds herself into the material for her art. In other words, she creates escape routes out of the fact of being cornered.

Paula Rego

The Raft 1985

Acrylic paint on canvas

242 × 192 cm

© Paula Rego. Marlborough International Fine Art. Photo: Pedrini Photography, Zurich

Born in 1935 in Lisbon to a liberal family, Rego grew up under the fascist dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar, who presided over the people like an ‘austere parent’ in the words of the British writer Barry Hatton in The Portuguese: A Modern History (2011). Portugal was a ‘stopped wheel’ for four decades, forced into a state of stagnation. According to the American writer Mary McCarthy, who visited Portugal in the 1950s, the elite lived in exile in their own country. Rego was a member of that elite. In the wonderful documentary about her life, Paula Rego: Secrets and Stories (2017), directed by her son Nick Willing, she says that upperclass women under fascism were admired for doing nothing at all. And yet, I write to her, you have done so much, and created so much. Did you cultivate a kind of double life – outwardly obedient and inwardly free? ‘It’s the best way for me,’ she replies.

Paula Rego

Dog Woman 1952

Graphite on paper

15.5 × 21.5 cm

© Paula Rego. Private collection

The Catholic Church was entwined with the regime, yet it seems Rego never lost her tenderness for the Virgin Mary. While the latter is typically shown in art with a chubby baby Christ on her lap, or weeping at the foot of his cross, or cradling his dead and wounded body in a Pietà, Rego shows the Virgin as a teenage mother, in labour. This is accurate: most biblical scholars estimate the Virgin’s age to be between 12 and 16 at the time of Christ’s birth. Nativity 2002, a small-scale pastel work, hangs in the chapel of the Portuguese presidential palace. Rego says in the documentary that ‘birth is a general feeling of sexuality and pain joined up together.’ I ask her if sex and pain are similarly joined in the creation of a work of art? ‘Birth is what happens automatically at the end of a pregnancy,’ she replies. ‘There is nothing automatic about making pictures. You’re never sure what will come out.’

Paula Rego

Dog Woman 1994

Pastel on canvas

120 x 160 cm

© Paula Rego. Private collection

At the moment, Rego is only interested in making religious images. ‘Nothing else is grabbing me,’ she writes. ‘Lila gave me the most wonderful stuffed lamb for Christmas. I’m using it in a picture.’ Lila Nunes is her long-term Portuguese assistant and model for such works as Dog Woman 1994, a large-scale pastel portrait of a woman on her haunches howling for her lost master. The image has a 40-year genesis: Rego made a small-scale black graphite work of the same name in 1952, when she was a student at the Slade in London. The first dog woman howls too, on all fours; hers is an alarming rage. ‘The dog women display raw emotions,’ Rego writes to me. ‘They were about my relationship with Vic.’

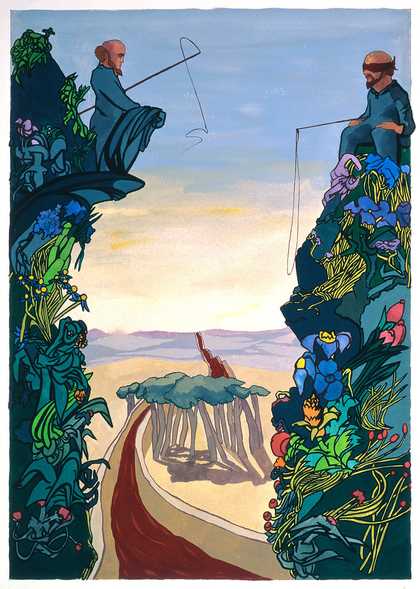

Paula Rego

The Two Neighbours Separated by a River of Blood 1975

Gouache on paper

70 × 50.2 cm

© Paula Rego. Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon – Modern Art Center, photo: Mário de Oliveira

Rego fell in love with the British artist Victor Willing when they were both students. They married in 1959 and raised their three children between London and Ericeira, Portugal, under the regime. Her early oil paintings are testament to her huge political courage. Salazar Vomiting the Homeland 1960 and When We Had a House in the Country [...] 1961 evoke a world in which men are reduced to semi-abstraction by their own cruelty. I ask Rego why she was not persecuted by the secret police? ‘I don’t know why not,’ she replies. ‘I think they didn’t understand my paintings. I had to change the titles because everything had to be checked by the censor. The full title of When We Had a House in the Country […] was When We Had a House in the Country We’d Throw Marvellous Parties and Then We’d Go Out and Shoot Black People. This was from a story overheard at a private club. The man was bragging about his time in the Angola war.’*

Paula Rego

When We Had a House in the Country We’d Throw Marvellous Parties and Then We’d Go Out and Shoot Black People 1961

Oil paint, graphite and paper on canvas

49.5 × 144.5 cm

© Paula Rego. Ostrich Arts Limited

In 2015, more than 40 years after the end of the Salazar regime, the Museum of Aljube opened in Lisbon in the former prison where dissidents were tortured. The horrors of fascism at home and colonialism abroad are now documented there. To date, no such museum about Franco exists in Spain, while Germany is renowned for addressing its own past. Indeed, I write to Rego, in Germany, Grimm fairy tales are sometimes viewed with suspicion as they appear to offer insight into the perversity and violence of the national psyche in a way that foreshadows Nazism. ‘You’re kidding,’ she replies. ‘I didn’t know that. That’s ridiculous. The stories are in all of us.’

The idea of a shared fund of stories is Jungian; it is the collective unconscious. Rego began Jungian analysis in 1966, and then eventually settled in London in 1972, where she still lives. She was inspired to make art based on Portuguese fairy tales, which was a turning point in her career. Far from whimsical, works in gouache such as The Two Neighbours Separated by a River of Blood 1975 had political overtones: in 1974, the Carnation Revolution ended the dictatorship in Portugal. Much of the power of Rego’s work is due to the fact that she has managed to carry over the urgency of the dissident artist into more democratic times and places.

Paula Rego

The Dance (1988)

Tate

Is there a relationship between Portuguese fairy tales and Portuguese fascism? I ask her. ‘Fascist propaganda is full of happy peasants and mothers raising babies at home,’ she replies. ‘All of them knowing their place in the fatherland. The Portuguese streak of perversity often came out in humour. Jokes were difficult to control. They were a form of rebellion.’

Recognition came late for Rego; in 1988, her exhibition at the Serpentine was celebrated and she was able to stop worrying about money. She was 53. Her husband had died of MS only months before and she was alone, like the solo female figure in her largescale acrylic painting The Dance 1988, who appears more powerful than all the couples swaying together under the full moon by the sea.

I send Rego a quote by Jung, which I love. ‘One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light,’ he writes in The Philosophical Tree (1945), ‘but by making the darkness conscious.’ ‘Well, quite,’ she replies. Much of your work appears to make the darkness conscious, both on a personal and a political level, I write to her. Do you feel this is the task of the artist? ‘I don’t feel I have a task,’ she replies. ‘I make work because it is all I can do. I find out what it’s about by doing it. Unexpected things come up. The trick is not to censor them.’

* Editor’s Note: In her essay in the catalogue for this exhibition, Giulia Smith writes about Rego’s anti-racist message in this painting, which ’explicitly targeted the colonial elite’. Its title’s jarring reference to abhorrent acts of violence comes from a real conversation her husband overheard in a club in Portugal. Smith states: ’In a mere twenty words, Rego managed to relay the perversity of a decadent and lawless system that trivialised the killing of people of colour to the point of treating it like a sport.’

Paula Rego, Tate Britain, 7 July – 24 October. Curated by Elena Crippa, Curator, Modern and Contemporary British Art with Zuzana Flašková, Assistant Curator, Modern and Contemporary British Art. Supported by the Paula Rego Exhibition Supporters Circle and Tate Patrons. Organised by Tate Britain in collaboration with Kunstmuseum Den Haag.

Zoe Pilger is a novelist and art critic. She is currently working on a series of four novels on women and art. She has won the Frieze Writers Prize, the Somerset Maugham Award and the Betty Trask Award, and she was shortlisted for the Anthony Burgess / Observer Award for arts journalism.