Cornelia Parker

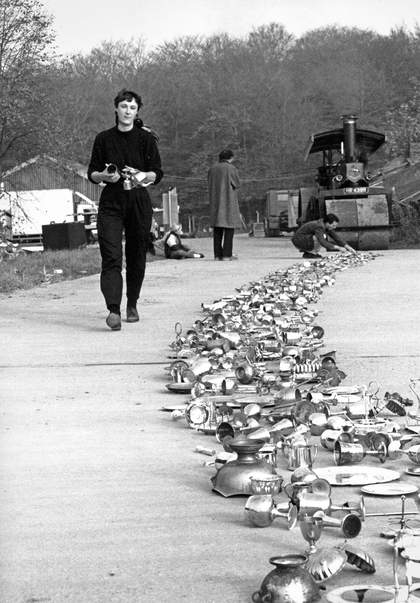

Thirty Pieces of Silver 1988 (work in progress)

© Cornelia Parker. Photo © Edward Woodman. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2022

Cornelia Parker was born in a world where much was certain, and much was blurred. Her father and grandfather were born on a smallholding in Cheshire, part of a long line of farm workers. But her mother was German and had been a nurse in the Luftwaffe during the war. She met Cornelia’s father when working as an au pair in a grand house nearby. Cornelia was the middle daughter of three girls. Since her father needed someone to work with him, she was brought up almost as a boy, learning how to dig and weed, and to milk cows by hand. Instead of dolls for Christmas, she got new wellies or tools.

She was 15 when she went with her art teachers to London to visit museums and galleries. She had never been in a city before. The first venue was Tate and she remembers thinking that one day she would like to exhibit there. In 1974, when she was 18, Parker did a drawing of a lapwing – just the head, dominated by a beak and an eye, with some feathers flowing back. It managed to be both precise and unsettling. But when she studied painting at Wolverhampton Polytechnic, she tussled with the idea of representation. She found it frustrating trying to depict light coming in through a window, for example. It made her retreat to a derelict house near the art school to work on visual analogies for light, including ones in three dimensions. She began to study sculpture, but rather than working with metal as the men did, she became as concerned with the space around things as with the things themselves.

She spent time in Reading, New York and then London, where she lived in a squat. Around her was a community of artists inhabiting houses due to be knocked down to make space for a motorway. The only thing she took back with her from New York was a small replica of the Empire State Building, which she began to make further replicas of in lead. She then suspended these upside down from the ceiling on metal wires. The more she reproduced objects, such as a souvenir Big Ben, the more they lost definition, becoming almost abstract. In 1986, at the Air Gallery in London, in a show called New British Sculpture, she had her work shown for the first time.

Cornelia Parker’s drawing of a lapwing she made aged 18

© Cornelia Parker. Courtesy of the artist

The previous year she had made one of her most astonishing early pieces, showing her mind, or her imagination, as brazenly and exquisitely original. She made lead casts of souvenirs of famous buildings and she put these in a gutter which she then flooded with bathwater. So, it looks like a flood disaster in a city with just the tops of the high building peering above the water. She made further lead casts of souvenir cathedrals and encrusted them onto a lifebelt that she floated near London Bridge. She made leaves in lead and attached them to dead trees.

Then she became interested in silver. It was, she saw, the most reflective of metals but with the potential to tarnish to black. Silver plate interested her more with its thin veneer over base metal. Every year her German godparents sent her pieces of silver cutlery, but they were never used since they required regular polishing. How many christenings, birthdays, weddings were marked by gifts of silver plate! How they represented an urge towards grandeur! And then how useless, underused they became, put in spaces for leftover things!

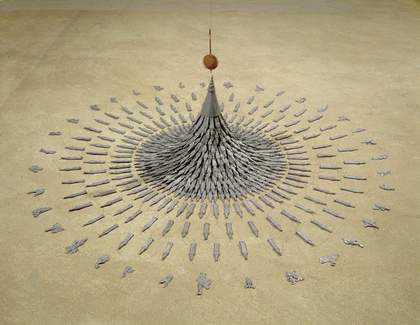

In 1988, Parker produced a work called Thirty Pieces of Silver. On a concrete drive, she placed various cheaply bought objects in silver plate, then had a steamroller flatten them. These were divided into 30 sections and suspended from a gallery ceiling. Obviously, the idea itself was thrilling, every child’s dream, but the installation itself was utterly beguiling and mysterious.

Fleeting Monument 1985 is made from lead casts of the handle of an ornamental bell, shaped like Big Ben which Parker found in a tourist shop in central London. She created hundreds of casts from one mould, during which process the clock tower gradually lost its definition. She has described her interest in these objects: ‘Souvenirs are bought as relics of something extraordinary. Through miniaturisation and reproduction, [they] become a crude abstraction, a useless ruin of the original.’

© Cornelia Parker. Photo © Arts Council Collection / Bridgeman Images

Parker is not looking to create a dreamworld, although the fears that dreams feed on can matter to her. Nor does she want to deface or dematerialise the known world as a result of some idea, even though she is interested in destruction. But it is never merely a single interest that animates her. She is also, for example, attracted by construction, creation, explosion: what will happen if you do something to an object, such as blow it up with Semtex (as she did with a garden shed in Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View 1991), or flatten it? What will emerge then? What emerges is pure excitement. And that too

interests her. Once she had blown up the garden shed, she hung the fragments from the gallery ceiling, lit from the centre so that they created intriguing shadows. Parker’s focus is not on spectacle so much as its aftermath, not on chaos so much as the arrangement of light around objects that have been transformed, or taken apart, or placed in a whole new context.

But, the mind of the maker, her own mind, also interests her and becomes part of the process. And it is perhaps the process itself, rather than its result, that fascinates her most. Her way of looking is dynamic. If she sees a relic from history or something from nature, her first instinct is to intervene, to do something, almost as a poet might wish to move a word or a phrase towards metaphor, or create a startling simile that will make the reader see an object in a totally new way.

Parker’s mother, who lived through the war in Germany, suffered from recurring bouts of mental illness throughout her life. An awareness of this history may help us to see some of her daughter’s work more clearly: Parker’s interest, for example, in derelict buildings, leftover things, explosions, fragments, transformations, instability. In 1994 Parker went to Germany and worked in the Ruhr Valley with a metal detector. She was emphatically not looking for treasure but for whatever was down there, useless things. What she would find was from a past that belonged not only to her mother but to her too, as someone who had had many conversations with German friends about their country’s history and philosophy. She suspended the objects she had dug up, and hung them so they hovered at a height corresponding to the approximate depth at which they were discovered.

To make Thirty Pieces of Silver 1988, Parker hired a steamroller to ceremoniously flatten more than 1,000 silver objects, including plates, cutlery, candlesticks, trophies and teapots. She then arranged the flattened objects into 30 groups and hung them about a foot from the gallery floor. ‘Silver is commemorative, the objects are landmarks in people’s lives’, Parker has said. ‘I wanted to change their meaning, their visibility, their worth. That is why I flattened them.’

© Cornelia Parker. Photo © Tate

In America, Parker became interested in guns, and, with her ingenuity, originality and sense of daring on full display, arranged for pearls and coins to be shot into a suit and a dress, thus creating holes. She shot a dictionary with a dime and then another with dice. Later, in 2007, she made bullet drawings, having had the lead from bullets melted down then drawn into very thin wire that she could arrange to resemble marks made by a pencil on paper.

In London, Parker began to look at ways she could transform and empower objects found in museums, such as a blanket and pillow from Freud’s analytical couch or a stocking that had belonged to Queen Victoria, spurs that had belonged to John Wesley or hats once owned by Henry Morton Stanley and David Livingstone. Or Napoleon’s rosary beads. Or Dr Crippen’s medicines.

In 1996, she purchased a meteorite, which she ground up and put into fireworks that were later exploded over the Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen. Thus, the crowd could see the fragments of the meteorite in a shower of sparks, the iron now appearing as light. In Texas the following year, she collected what was left of a Baptist church that had been struck by lightning and suspended the pieces from the ceiling.

Obviously, it helps each time for viewers to know the context of a piece, how it was made and what it was in its earlier state. If the inspiration for Parker’s work comes from dreaming, it seems that she confines her dreaming to first imagining what to do with the objects she finds, and then to dismantling them or defamiliarising them. Once that is done – once she has the flattened silver or the charred remnants of the church – Parker then puts her mind to recreating them in a very deliberate way. There is no dreaming now; it is all thought through, all planned out. Parker, thus, works as both a conceptual artist and an old-fashioned sculptor. The way she arranged the burned and charred fragments, for example, is startling, arresting. Even if you didn’t know the context, you would stop to study it.

If you were to ask ‘What is Cornelia Parker saying?’, the answer would be that this is not a good question. Parker is not making statements. She is seeing where something might take her, some what-if, some far-fetched way of transforming things, or enacting transformation. She is not making easy connections but imagining what solid things, if arranged or rearranged, might look like in light. Or what that light might look like with these new objects hanging as though freely from the ceiling. Thus, her impulse is visual rather than intellectual. She seeks to see things differently, to rearrange. It is almost as simple as that. But nothing in her array of ambiguities is ever really simple. She wants to make something that is both abstract and representational at the same time.

In Texas, she saw Davy Crockett’s cut-throat razor in the Alamo Museum. Part of her job as an artist was to work out a way of getting permission to take it and make cuts in paper to produce a drawing that resembled the work of Lucio Fontana. When she saw a sword that had been owned by Henry VIII at the Tower of London, she sought permission to pierce a pillow with it. It might be easy for us to feel that this is all tremendous fun, a jamboree of zaniness created to amuse us or distract us. Dark laughter; dark wonder. But that would be to miss the point. Parker does not take a cut-throat razor or a sword lightly. In fact, she seeks a way of making them haunt us more intensely.

And there is other work that Parker has done that is even more grave, more disturbing. What are we to do with objects that are still in existence, relics of pure evil, that make us shudder? The fact that Hitler loved classical music is bad enough, but what should we do with Hitler’s own record of the Nutcracker Suite? What a pity it was not destroyed!

One of the four photographs Parker took of the sky over the Imperial War Museum in London with a camera that belonged to Rudolf Höss, commandant of Auschwitz concentration camp, for her series Avoided Objects 1999

© Cornelia Parker. Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London / Photograph Cornelia Parker

In 1996, Parker took a photograph of the surface of the record through a microscope. It was all grooves and marks, so that it looked like an aerial photograph of ploughed fields. Three years later, she discovered that the Imperial War Museum owned the camera that Rudolf Höss, the commandant of Auschwitz, had used to take photographs of his family. There was, she thought, something chilling about the idea, once more, of the Nazis posing as ordinary people, and the awkward objects that they have left us. She got permission to put film in Höss’s camera and take it outside the museum. But what to photograph? Her aim here was not ironic or humorous. She did not seek to dilute what was chilling and disturbing, but to work with the idea that these objects, so innocent looking and so ordinary, were infused with an evil that would never leave them. The film she used was infrared. She took photographs of clouds in the sky.

Does the fact that the clouds were photographed by this very camera, change the clouds? It is not as though Parker was making some banal point here about the banality of evil. She was not making any point at all. No one looking at these images will be sure what to make of them. These photographs of the sky and of the surface of Hitler’s record have implications that will not settle or go away.

This, then, has been Cornelia Parker’s project: to work towards some shivering level of ambiguity in a world still haunted by relics, leftover objects, things that cry out to be transformed. Her genius consists not just in her intellectual restlessness but also in her interest in revisualising the world, creating images that disturb and startle, that fill the air around them with what has been newly imagined.

Colm Tóibín is a novelist. His latest book The Magician won the 2022 Rathbones Folio Prize.

Cornelia Parker, Tate Britain, 19 May – 16 October. Curated by Andrea Schlieker, Director of Exhibitions and Displays, Tate Britain, with Nathan Ladd, Assistant Curator, Contemporary British Art, Tate Britain. Supported by the Cornelia Parker Exhibition Supporters Circle, with additional support from Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons and Tate Members.