Digital media and computer-generated images have transformed our visual culture and made previous technologies such as video and film seem old-fashioned and technically limited. The dramatic expansion of visual media in the late twentieth century and at the beginning of the twenty-first has created renewed interest in earlier moments in the history of the visual arts when new technologies appeared, challenging existing media and transforming the cultural landscape. Recently, art and film historians have looked again at the formative years of cinema, when films were first projected to large audiences in music halls and fairgrounds at the end of the 1890s, and have begun to examine how film engaged with already established popular media such as lantern slide projection, and with the traditional arts of painting and sculpture.

There is a group of films, made in these early years, that take as their subject the artist’s studio and tell us a great deal about how film - the new kid on the block - regarded fine art - the elder statesman – in this critical period of cultural transformation. They are short, usually little more than a couple of minutes, and use a range of camera techniques, such as stop-motion effects, multiple exposure and dissolves, to create magical effects of appearance and disappearance, substitution and replication, animation and petrifaction. The artist’s studio is the setting for the new medium to perform its astonishing visual tricks; a magical space in which paintings are made in the blink of an eye and pictures come to life and taunt the bemused painter. Devils appear from thin air and wreak artistic havoc, and artists are invariably made to look like fools. Although fine art had much greater cultural value and status in the 1890s than cinema, these works can be seen as the way in which the first film-makers asserted their technological superiority and illusionistic skills. Thus if a painting could imitate reality, then film could go one better and actually animate the picture and transform it into a living form. The artist’s studio became a battleground for a fascinating and frequently comic cultural struggle between art and film.

The number of trick films in the late 1890s and early 1900s featuring the enchanted painting is very striking indeed. Thomas Edison’s An Artist’s Dream (1900) opens in a studio, with the painter asleep in a chair and two elaborately framed full-length female figures in the background. A Mephisto character suddenly appears and brings the paintings to life, and there follows a breathtaking sequence of magical transformations that tease and harass the artist, until Mephisto finally returns the women to their frames and disappears into thin air. The puzzled artist is left looking at the framed pictures and having a stiff drink. This is a short, but action-packed rough comedy with the viewer’s attention being drawn rapidly from one filmic trick to another. In the British filmmaker Robert Paul’s The Devil in the Studio (1901), the artist is again subjected to a series of humiliating transformations when Mephisto materialises from a tube of paint as he is painting a model. Paul’s trade catalogue describes the ensuing play with visual images:

The painter is astonished to see work done without effort, and shakes his head dubiously at his own portrait filling the canvas… The canvas is once more blank, and, as the artist stands… he perceives, to his great amazement, that the model is slowly fading from her platform, and at the same time is gradually appearing on the canvas like a developing photograph… the artist, in a transport of delight at the production of a painting in a few minutes, rushes from the studio and quickly returns with a dealer… Just as they turn to look at the picture, it immediately changes to a comic caricature making fun of them.

Driven wild with frustration at the demon’s tricks, the painter finally wrecks his own canvas and smashes up the studio.

Artists in these films are a pretty sorry bunch. Either sleeping, or in a state of waking amazement, they are rarely at work and are always outdone by the magic effects or their demonic personification. It can often seem, in enchanted painting films, that their central purpose is to undermine the long-established mythology of artistic creativity. Trick effects are used to flaunt the ease with which film can simulate the making and unmaking of art and impart life to the lifeless image – often leaving the artist in a state of helpless rage, or resigned sleep.

Thomas Edison’s The Artist’s Dilemma (1901) begins with the familiar scene of the artist asleep in his studio. The door of a carved grandfather clock opens and out steps a female figure in a dancer’s costume. She wakes him and he takes her to a raised platform and indicates that he wishes to paint her portrait. He takes up his palette, brushes and mahl stick and is just about to start working on his canvas when another person emerges from the clock. Half clown, half demon, this is the genius technologi, the spirit of film, who will unravel all the painter’s attempts to produce a likeness of the model.

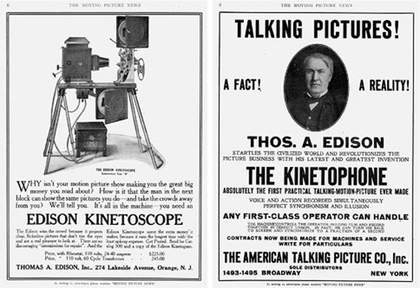

Moving Picture News, 18 January 1913 and 29 March 1913

Magazine pages

Courtesy Library of Congress, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division

The clown gestures that he can do a better job and reaches into the clock to grab a large bucket of paint and a huge brush. With a few strokes he covers the canvas and, to the distress and amazement of the artist, creates a perfect portrayal of the model. This section of the film was achieved by reverse motion, producing the illusion that the picture is completed in a few rapid strokes. But there is more. The clown then goes over to his painting and brings the woman to life; together they taunt and ridicule the artist, who is finally left alone with a blank canvas. Through the figure of the demon/clown, film usurps all the illusionistic functions of art. It can make and unmake painting in a moment, and it can animate the lifeless image. The artist is the dupe; turned upon by both his model and his living image. There can be no artistic genius or masterpiece in this bizarre world, just the defeated painter and the agonising blankness of the empty canvas. No discussion of enchanted pictures in early film would be complete without special reference to the oeuvre of Georges Méliès. In so many of his works, there is a shifting between the states of lifeless image and living form. Almost every type of visual image is animated: statues, paintings, advertising posters and playing cards are all magically brought to life, only to confound the human world in which they find themselves. The number and inventiveness of Méliès’s films on this theme suggest that it held a special fascination for him and that he was drawn to its symbolic significance as a metaphor for the animating power of film and to its focus on the relation between still and moving images.

Perhaps more than any other individual figure in this period, Méliès embodied in his life and in his work the relationship between magic, art and technology. As a boy in Paris he had wanted to train as a fine artist, but had been refused by his parents. In 1884 he was sent to live in London, and it was during this stay that he came into contact with the spectacular stage effects that characterised pantomime and magic theatre in the 1880s. Méliès became hooked on magic; he studied the great illusionists and practised and honed his own prestidigitatorial skills. On his return to Paris he began giving performances, and when his father died in 1888 he sold his share of the family business and set up his own magic theatre on the Boulevard des Italiens, a few minutes’ walk from the Grand Café, where the Lumière Cinematographe was given its first public performance. Méliès clearly realised the commercial possibilities of film; he got hold of a projector, bought films from Edison and Paul and introduced them into the programmes at his theatre. He quickly moved into film production, developing his own camera, purchasing film stock and erecting a studio in his back garden.

Georges Méliès

A Trip to the Moon c.1902

Film set

© Courtesy Rue-des-Archives

The question remains why so many of Méliès’s special effects were performed on the still image. He might have attended the École des Beaux Arts and become a fine artist, and it is clear that his pictorial imagination continued to work in terms of still images throughout his film-making career. Art was the foundation of his creative life and it is as though he continually returned to it as he developed the range of his film style.

These issues are explored in his extraordinary trick film The Mysterious Portrait, made in 1899. The focus is on a large, ornately carved, but empty picture frame. Méliès enters and, drawing on gestures and devices from the magic theatre, he demonstrates to the audience that the frame is, indeed, empty and that the apparatus is not rigged. He takes a canvas depicting a rural landscape, places it inside the gilt frame and then sits beside the picture. He gestures to his own face and makes a magical sweep of the canvas; the picture slowly darkens and gradually the blurred photographic image of Méliès – dressed identically to the man himself – begins to appear. When the transformation is complete, Méliès’s double sits inside the frame in a formal, seated pose. Slowly, the portrait turns to its creator; they greet each other and begin a sequence of echoed gestures and actions. The magician then makes an expansive motion with his hand and the figure gradually disappears until only a dark rectangle remains inside the frame.

Méliès achieved the illusion by using a matte shot. The part of the camera lens where the portrait would be was masked and the rest of the scene shot; the film was then rewound and the living portrait filmed while everything else was blocked out. The Mysterious Portrait extends the genre of the enchanted painting by having the animated portrait holding a dialogue with its living, film counterpart, and, just at the point at which it seems that the portrait must break free of the frame, Méliès magics it away. The picture lives and moves, but only within its gilded confines.

In the first decade of the twentieth century there were major changes in the business of filmmaking. The medium was a success and the issues of organisation and profits, standardisation and control became the most pressing debates at the first Congrès International des Editeurs du Film that took place in Paris in 1909. Méliès was elected president of the association, but nevertheless found himself accused by the French film company Pathé of being only “an artist” and of not understanding business. He replied: “I am only an artist, so be it… I say the cinema is an art, for it is the product of all the arts.”

The relationship between art and film continues to be a contested one, and the exhilarating images of early cinema show us the first moments of this ongoing cultural debate. The enchanted painting was a metaphor for the new medium and its representational powers. The young upstart surpassed the illusionistic capacities of the traditional arts and flaunted its special effects to ridicule the artist. In the trick films of the great pioneers such as Edison, Paul and Méliès the art image and the film image can be said to be in an aesthetic dialogue, jockeying for position and influence in the new world of twentieth century visual media.