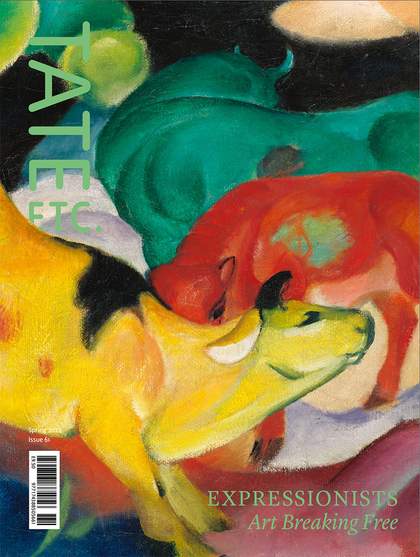

Franz Marc

In the Rain 1912

© Lenbachhaus Munich / Bernhard and Elly Koehler Foundation

The highest values of art are not identical with mere national characteristics. It is a characteristic of all great art that it projects into the sphere of general humanity.

Heinrich Wölfflin, 1912

We were only a group of friends who shared a common passion for painting as a form of self-expression. Each of us was interested in the work of the other ... in the health and happiness of the others ... I don’t think we were ever as programmatic in our theories, as competitive or as self-assertive, as some of the modern schools.

Gabriele Münter, interviewed by Edouard Roditi in 1958

What comes to mind when we hear the term ‘expressionists’? On the one hand: instantly recognisable bold, pure colours, dramatic forms and gestures, the expressive distortion of forms, atonal music, free verse, the angst of the early silent cinema, decadent tastes, the medieval striving for the symbiosis of artistic forms. On the other: an artistic reaction to the human, political and societal conditions of a period of imperialist ambition and colonial expansion, ethnic intolerance, class struggle, and crisis surrounding the fate of the early 20th century.

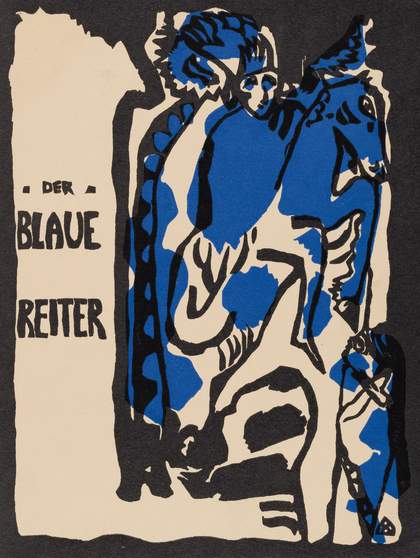

Against this backdrop emerged a unique transnational community of creatives united by the values outlined in their programmatic publication The Blaue Reiter Almanac (1912). The collective was the first to proclaim the values of transculturality as key to their creative project. As the draft preface to the Almanac stated: ‘In our case the principle of internationalism is the only one possible ... The whole work, called art, knows no borders or nations, only humanity.’

The Blue Rider’s historiography presents it as a Munich-based group founded in 1911 by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, who in 1911–12 organised the First and Second Exhibition of the ‘Blue Rider’ Editorial Board and published an illustrated volume of collected texts by artists and musicians juxtaposing modernist art and contemporary trends with tradition. Their subscription prospectus boasted:

Blaue Reiter ... will be the call that summons all artists of the new era and rouses the laymen to hear ... The first volume ... includes the latest movements in French, German and Russian painting. It reveals the subtle connections with Gothic and primitive art, with America and the vast Orient, with the highly expressive, spontaneous folk and children’s art, and especially with the most recent musical movements in Europe and the new ideas for the theatre of our time.

Erma Bossi

Circus 1909

© Lenbachhaus Munich / Permanent loan from the Gabriele Münter and Johannes Eichner Foundation, Munich

As this suggests, the intention was for the publication to become a periodical. Plans for a second volume were discussed and drafted, only for the project to be abandoned with the outbreak of the First World War, when co-editors and contributors found themselves citizens and subjects of enemy states.

Traditionally, three factors of the Blue Rider enterprise are highlighted as key in discussions of its history: the intense period of experimentation in the rural Bavarian town of Murnau; the activities of the collective’s predecessor, the Munich-based New Artists’ Association (Neue Künstlervereinigung München, or NKVM); and the much-mythologised meeting of the co-editors Kandinsky and Marc in January 1911. It is certainly the case that in the 1900s Munich provided a (relatively) liberal and progressive environment to forge artistic experimentation, attracting misfits and marginalised artistic individuals from even less tolerant societies: artists with Jewish ancestry from Eastern Europe and America (Albert Bloch, Elisabeth Epstein), creatives from the melting pot of the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires (Alexander Sacharoff, Erma Bossi), those who couldn’t fit socially within their own middle-class privileged social milieux (Wassily Kandinsky, Maria Franck-Marc) or those in pursuit of unconventional partnerships (Marianne Werefkin, Alexej Jawlensky). The city enjoyed prosperity, a culturally sophisticated ruling family and a conservative but well-established middle class capable of supporting and sustaining diverse artistic experimentation in the field of visual arts, architecture, literature, music and performing arts. A thriving academic and scientific community provided intellectual stimuli, while the neighbourhood of Schwabing, which housed the Academy of Fine Arts and the University, offered a progressive community.

Franz Marc was the only Blue Rider artist to be born and raised in Bavaria. Kandinsky, Jawlensky, Werefkin, Epstein, Sacharoff, brothers David and Wladimir Burljuk and Sonia Delaunay originated from the vast lands of the Russian Empire. Münter, Franck-Mark, and August and Elisabeth Macke joined from other German lands; Paul Klee was Swiss-German, Arnold Schönberg and Bossi hailed from Austro-Hungary and Robert Delaunay from France, while Bloch and Lyonel Feininger started and finished their lives and careers in the US. A gap of 27 years separated the oldest from the youngest ‘riders’, and artistically they were at different stages in their careers. Yet all were linked by Munich, a place imbued with possibilities, and which had different significance to each artist.

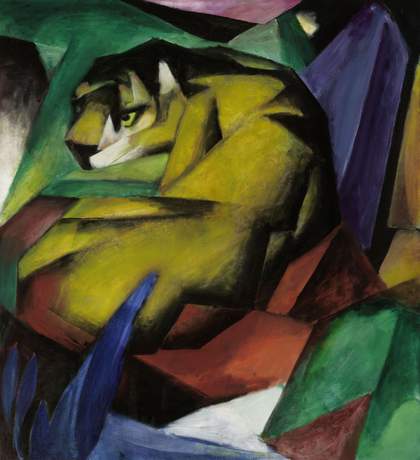

Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, Der Blaue Reiter, published by R. Piper & Co., Munich, 1912

© Tate, 2024 / Larina Annora Fernande

Poster for the First Exhibition of the New Munich Artists’ Association, with a colour lithograph by Wassily Kandinsky, 1909

© Lenbachhaus Munich

Werefkin and Jawlensky, who met in 1892, moved to Munich to advance their painterly experimentations and pursue their unorthodox relationship. Their presence drew into the circle of Werefkin’s intellectual salon Kandinsky, Epstein, Sacharoff and others who had come to Bavaria to study. Kandinsky met Münter and Bossi in 1902 when he was teaching at the Phalanx school, while others connected through the exhibitions and activities of the NKVM. Robert Delaunay made acquaintance with his future wife Sonia Terk in Paris in 1907, and befriended Feininger who moved between Paris, Berlin and Weimar. Marc and Macke met in 1910 and developed a lifelong creative bond that ignited their innovative styles and brought them within the sphere of influence of Kandinsky and Münter. The solitary figures of Klee, Marc and Robert Delaunay were given impetus towards creative experimentation through intellectual discussions with other members of the circle from 1911 – the year the idea for the Blue Rider was conceived. Various degrees of separation connect those and many other artists, forming concentric circles of friendship, intimacy, collaboration, spiritual kinship and comradery, with Kandinsky and Münter at their centre.

The Blue Rider’s appearance on Munich’s art scene was an act of rebellion against its predecessor, the NKVM, and followed the summer of 1908 that Kandinsky, Münter, Werefkin and Jawlensky spent working en plein air in Murnau. This town – and the house Münter bought there in 1909 – became a hub for the two couples as well as such key contributing members of the Blue Rider as Marc and his partner Franck-Marc, August and Elisabeth Macke, Bossi and Heinrich Campendonk, as well as the composers Thomas von Hartmann and Schönberg. Both Murnau and the surrounding sub-Alpine landscape played an important role in the artists’ experimentations with colour, composition and non-figuration, and in their artistic development.

During this time, fuelled by the rejections of their experimental work by the jury of the Munich Secession, Jawlensky, Alexander Kanoldt, Kandinsky, Münter, and Werefkin formed an avant-garde association: the NKVM. As Münter recalled in a diary entry from 1908, they were striving to create an art in which to ‘feel the content of things’. Officially founded in January 1909, the NKVM was one of the first such associations to offer equal membership rights to women. It drew an increasingly international circle of creatives that included Wladimir Bechtejeff, Alfred Kubin and Henri Le Fauconnier, as well as performers such as Sacharoff and musicians such as von Hartmann.

Gabriele Münter

Village Street in Winter 1911

© Lenbachhaus Munich / Donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957

The NKVM was structured as an association with membership, chairmanship, an exhibition programme and a selection committee, but it was also open to ideas of diversity, which attracted Marc to join in January 1911. The intense discussions between Kandinsky, Münter, Marc and, later, Macke on the mode of reconciliation of the ‘material’ with the ‘spiritual’ in their art led to the idea of a periodical publication which would provide a platform for the discourse and connect with likeminded creatives drawn from the NKVM’s ever-growing international network. By June 1911, the ideas for a yearbook were put to paper, and in October of that year content meetings were held in Murnau that would lead to the publication of The Blaue Reiter Almanac in May 1912. The work of its two credited co-editors was ably supported by research, networking activities, correspondence and negotiations by Münter, Franck-Marc and Elisabeth Macke, who remained uncredited.

The mission set forth by Kandinsky and Marc in their conception of the Almanac centred around the ‘inner’ motivation of the artist. Importantly, however, their aims reached beyond art, aspiring to a renewal on a grander scale. In Marc’s words, ‘art was concerned with the most profound matters, that renewal must not be merely formal but a rebirth of thinking’. Within months, the ambitions of this loose confederation had outgrown the increasingly moderate frame of the NKVM, and, under the pretext of protesting against the exclusion of Kandinsky’s abstract painting from the NKVM’s third exhibition of December 1911, Kandinsky, Marc and Münter resigned from the association. Instead of founding a new faction, they acted decisively and radically by curating their own parallel show, staged at the same gallery just two weeks after the breakup.

The First Exhibition of the ‘Blue Rider’ Editorial Board (Erste Ausstellung der Redaktion Der Blaue Reiter) opened on 18 December 1911 and included the three rebels as well as friends who were already associated with the work on the forthcoming yearbook: Henri Rousseau, Bloch, the Burljuks, Campendonk, Robert Delaunay, Epstein and Schönberg, among others. The catalogue’s preface stated: ‘Through this small exhibition we do not wish to propagate a single precise and specific form; rather we intend to demonstrate through the diversity of the represented forms how the inner desire of artists manifests itself multifariously’. The ‘pop up’ exhibition attracted another wave of young experimental artists including Hans Arp and Klee.

Wassily Kandinsky

Bedroom in Ainmillerstrasse 1909

© Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957

The second exhibition was staged just seven weeks later under the title Black and White (Schwarz-Weiß) and showcased works on paper and prints. Opening on 12 February 1912 at the Galerie Neue Kunst – Hans Goltz, it presented even more heterogeneous content than its precursor, with 315 works by 31 artists including Klee, Kubin, Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso, and Brücke artists Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. In addition, Kandinsky included popular prints from his folk art collection. Münter, Epstein and Goncharova (Gontscharowa in the catalogue) were the only women artists who contributed. In the meantime, the first show went on tour, amid preparation for the launch of the Almanac in the spring of 1912.

That yearbook – celebrated for its experimental content, avant-garde editorial work and non-hierarchical approach to representing works by both Western and non-Western artists – was as contradictory as its times. The publication brought together artists and musicians from across Western and Eastern Europe and America, while its diverse content promoted a new synthesis of the arts as well as principles of ‘total abstraction’ and ‘total realism’ of a fundamentally ‘spiritual’ nature, answering the editors’ call for ‘inner necessity’ in arts. All text contributions, however, were by male artists (although Emmy Worringer, co-founder of Cologne’s Gereonsklub, was considered), while only Münter and Goncharova’s works were featured among the illustrations. Although art historians still ponder the controversial use and juxtaposition of imagery of spiritual significance and the ruthless editing of images, as well as the frequent recourse to colonialist terminology, the publication provided an innovative approach and fostered closer collaborations between the visual arts and music, theatre, vernacular art forms, children’s art, global traditions and transhistorical aesthetics.

The ensuing dialogue between form and content in the work of the Blue Rider artists is such that it invites new readings and interpretations with every successive generation, the present exhibition at Tate Modern being just one step along a well-travelled road. While the wealth of research, publications and resources available on these artists signals the impossibility of comprehensively summing up the Blue Rider project in a single exhibition, it allowed us to adopt a number of narrative lenses, all guided by a set of key questions: ‘Who are the people behind the Blue Rider creative project, and how did each of their individual biographical trajectories contribute to the common task?’, ‘How did the Blue Rider – so often contextualised within the German expressionist movement’s history and aesthetics – become the first transnational circle of artists of the Western modernist period?’ and ‘How can a horizontal way of considering their individual and collective practices help us to reconsider the modernist canon?’

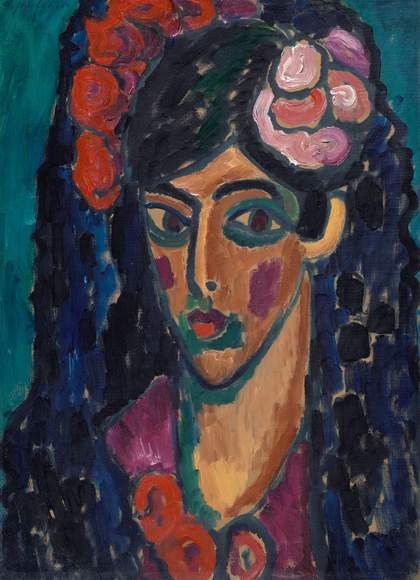

Alexej Jawlensky

Spanish Woman 1913

© Lenbachhaus Munich

The Blue Rider circle of artists was a broad church, in which varying degrees of separation generated overlapping spheres of interpersonal relations. In the Expressionists exhibition, we have concentrated on just a few of these artists and their circle of influence, endeavouring to sketch the ecliptic plane of symmetries and disjunctions, contradictions and assertions that determined their approach to form, medium, sound and movement as equally valid means of cultural manifestation.

Academics and scholars still struggle with the classification, chronology and genealogy of a movement that hailed the dramatic shift between tradition and modernity. Yet, it was expressionist artists’ ideas, modus operandi, propensity towards crossing the boundaries and questioning of distinctions between art and non-art that gave licence to the generation of artists who emerged in the 1950s and 1960s to affirm experimental art forms such as performance, happenings, eco-activism, installation, time-based media and sound art.

We remain conscious of the fact that these artists were involved in – indeed, largely instrumental in setting up – the structures of a canon of modern art that, as art historian Dorothy Price has put it, ‘was to remain mute for many decades about the inherent violence on which its very modernism was premised’. As scholars and museum curators grapple with the legacies of modernism as reflected in postcolonial discourse and understood in the context of culture transfer, new approaches developed in the past 15 years reveal the importance of emancipative ideals forged within the circle and highlight the Blue Rider’s legacy for contemporary aesthetic practices. In his preface to the second edition of the Almanac, released just before the outbreak of the First World War, Marc revealed that the ambitious project of the Blue Rider would require a radical societal change ‘when the cult of modernity has stopped trying to industrialise the virgin forests of new ideas’ – a notion that would strongly resonate with our creative community of today.

Wassily Kandinsky

Impression III (Concert) 1911

© Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957

Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and The Blue Rider, Tate Modern, 25 April – 20 October. Presented in the Eyal Ofer Galleries. Supported by the Huo Family Foundation with additional support from Tate Patrons and Tate Members. The media partner is The Times and The Sunday Times. Organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with Lenbachhaus Munich. Curated by Natalia Sidlina, Curator International Art, Tate Modern and Genevieve Barton, Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate Modern.

Natalia Sidlina is Curator, International Art at Tate Modern. Full versions of this article and chronology are included in the exhibition book Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and The Blue Rider, published by Tate Publishing.