Roshini Kempadoo

Impressions Passing 1992

© Roshini Kempadoo

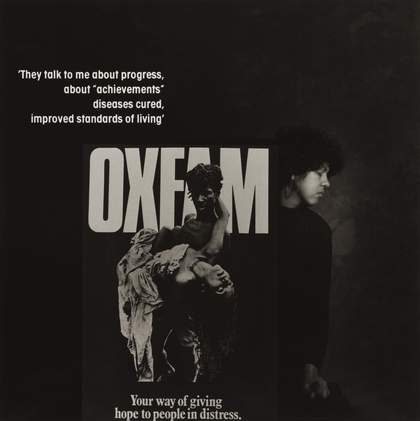

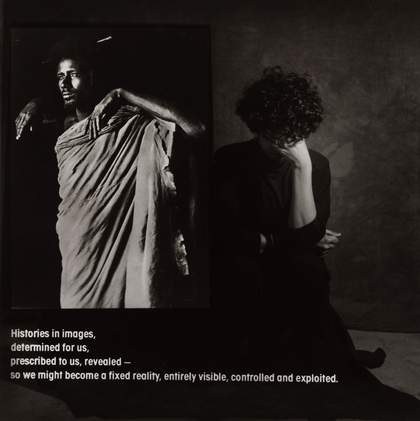

There are times when you have to create. When it becomes urgent to make something in response to what you are seeing, feeling, witnessing. Something builds up inside of you – a feeling of being overwhelmed by the anger, sadness and tragedy, the injustice of it all. Making Impressions Passing 1992 was a way of ‘saying it like it is’, a straight talking of sorts. To speak it, visualise it, then release it, is good for the soul. It shares the burden and allows a recovery to begin. It was one of those times. As it is now:

‘… a rightwing wave sweeping

across the globe like a demonic

cloud of hate’

– Skin (Skunk Anansie),

Guardian, 25 January 2025

In 1991, I interned with the National Museum of African Art at the Smithsonian in Washington DC. I was tasked with cataloguing slides from the Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, in particular a collection of travel photographs taken in Leopold II of Belgium’s privately owned country, the Congo Free State, which existed between 1885 and 1908, and covered much of the modern Democratic Republic of the Congo. To me, these images evoked the brutality and horror of colonialism in its extreme. On my return to the UK, I felt the need to respond to the images I had seen.

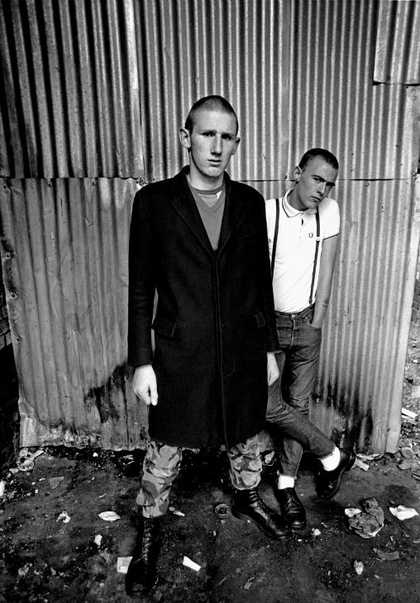

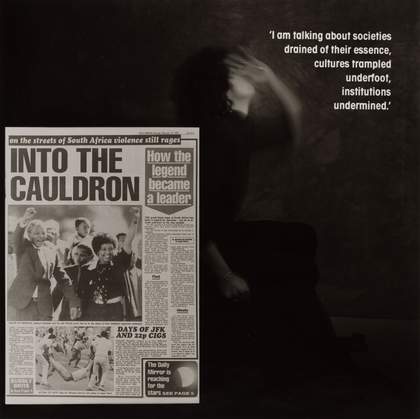

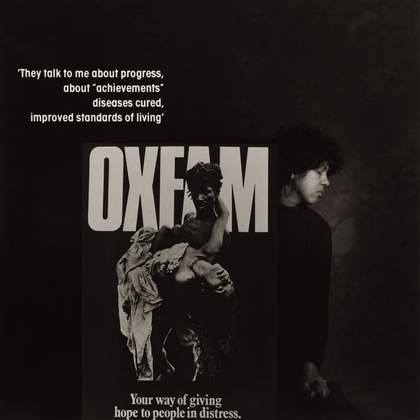

The result was Impressions Passing, a series of eight black and white photographs created in my studio and darkroom in Leicester. I took to creating assemblages of texts I had either written or been influenced by, set alongside adverts, magazine covers and historical ethnographic images, which I had been collecting obsessively (and still do). I saw these images as the colonial afterlife: visual traces found everywhere in the popular media and in our everyday circulation of images, embedding racist attitudes that continue to haunt and torture us. In the end, the darkroom, which had once been a space of contemplation and calm, increasingly became a place of isolation overwhelmed with spectres of the colonial past.

Roshini Kempadoo

Impressions Passing 1992

© Roshini Kempadoo

Roshini Kempadoo

Impressions Passing 1992

© Roshini Kempadoo

I superimposed these documents of the incorrigible and visceral force of racism and dehumanisation onto an unexposed space in a series of self-portraits taken with a medium-format camera. Self-portraiture allowed me to rehearse and document the Black body in protest. I continue to rehearse and perform acts of resistance to this day, to hone in on a capacity for the body to stage resistance. Sometimes I look for it in other women’s bodies. I ask the question: What does the Black woman’s body look like in defence of herself, in various forms of resistance or in defiance?

Some 30 years on, I remember Impressions Passing as being the time of what I describe as a ‘creative conjuncture’ – a concurrence of events that instigated change in my work. The series was a tipping point in my use of historical and stereotypical visual tropes. I questioned how visible these kinds of persistent images needed to be. It also marked the move I made from the darkroom and black and white photography to a digital form of image making. I felt I could contribute to visualising injustices in other ways, making use of the screen, post-production software and image sequencing.

My practice continues to morph alongside my commitment to social change and climate change. I continue to make images of Black women’s bodies in defiance, drawing on images from anti-racist movements and climate activism. In this way, I am developing radical ideas and new modes of creating work. Making transparent colonial legacies, Black life and planetary precarity, here and now, necessarily requires more – so much more – in the way of imaginative experiments and visual responses to current political and ecological crises.

Six works from Impressions Passing are included in The 80s: Photographing Britain, Tate Britain, until 5 May.

Roshini Kempadoo is a photographer, media artist and scholar who lives and works in London.