Mona Hatoum in the living room of her family home in Beirut, c.1955

Photo courtesy of Mona Hatoum

I grew up in Beirut, Lebanon, in a home that was loving but also strict in many ways. Like many Palestinians who had lost all their worldly possessions, my parents were inclined to focus on giving us three sisters the best education possible – something no one could take away from us. My father put pressure on us to get the best grades at school, but, unlike my eldest sister, who was a straight-A student, I was happy just to pass my exams and be left alone.

I was the creative one, often caught drawing in the margins of my notebooks in lessons. As the youngest, I was also rebellious, though I was not allowed to distract my sisters from their studies. I had to keep quiet in my corner, where I would play with empty tins and jars, or draw. I had this idea that artists were permitted the freedom to make their own rules, so becoming one felt like a way to go against the social conventions around me.

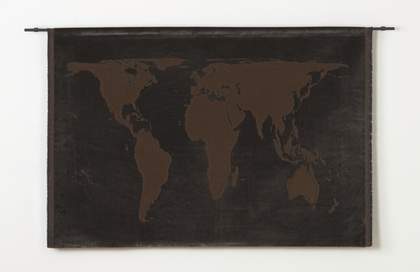

I would lie on the balcony and spy on people with binoculars, imagining that, with my magic binoculars, I could see through clothing and skin, right to the bone. This was the curiosity of a child about what lies beneath the surface, the questioning of taboos and social norms. It is funny, then, that in the first series of performances I created in the early 1980s, I used a live video camera to scrutinise members of the audience as a way of pointing to issues of surveillance and the invasion of boundaries.

We had limited resources growing up, so my parents were practical. Every Christmas I was given the same pair of red boots in a bigger size. No toys, nothing frivolous. One year an uncle gave me a Meccano set – an unusual gift for a girl. I loved it! I spent endless hours bolting together the red and green metal strips to make various structures. Metal grids have since been central to my work, turning into cages to reference control and surveillance, and, ultimately becoming the architecture of a prison.

I remember my mother looking over my shoulder with words of encouragement at my creative endeavours, and my father must have appreciated my drawings too, because after he died, I was surprised to find that he had kept all my illustrated notebooks since kindergarten. However, when I expressed interest in going to art school, he opposed it. He wanted me to specialise in something that would guarantee a job. As a compromise, I enrolled on a graphic design course and worked in the field for a few years before I felt I could go it alone.

In 1975, I finally quit my job and planned to return to Beirut University College to study for a BA in Fine Art. Before I started, I decided to visit London – my first trip to Europe. However, while I was there, the Lebanese Civil War broke out, and I couldn’t return home. I had to support myself in London through scholarships and by working evenings and weekends. That short stay turned into a lifetime as London became, and still is, my main base.

Looking back, I see that my mother’s greatest frustration was that she was not allowed to continue her education beyond primary school. In those days, women were supposed to be primed for marriage and children, and she experienced domesticity as confining and limiting her freedom. The caged-in, domestic environments that I have been creating since the late 1990s are probably an expression of how she felt about her domestic existence. I feel that I have ended up with the life she wanted but could not have.

Mona Hatoum’s installation Current Disturbance 1996 was presented as part of the D.Daskalopoulos Collection Gift in 2023 and is on display in Modern and Contemporary British Art at Tate Britain until 21 June 2026.

Mona Hatoum is an artist who lives in London. This piece was adapted from an interview in Dream On Baby: Artists and Their Childhood Memories by Gesine Borcherdt, published by Hatje Cantz.