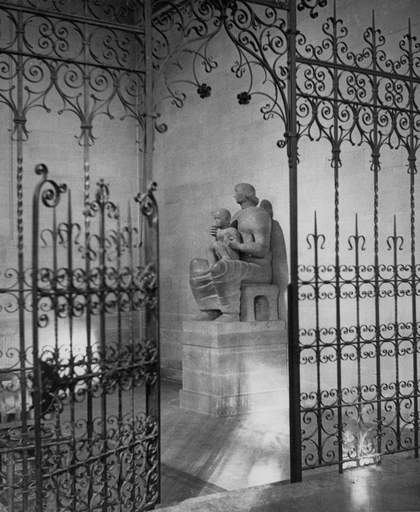

Louise Bourgeois

Maman 1999

© The Easton Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2025

I associate Louise Bourgeois's monumental spider sculptures with her largest, the steel Maman 1999, which was outside Tate Modern when I lived in London. It was first installed inside the Turbine Hall for the opening of Tate Modern in 2000, again in 2004, and then outside in 2007 to coincide with Bourgeois’s solo exhibition. That was when I encountered her series Cells 1986–2008, which would be the catalyst for my writing Book of Mutter (2017), a text on my mother. I know this because there is a photograph of a young me, arms crossed, in front of the spider.

I think of the 10-metre-high Maman nestled within the chilly architecture of London and the alienation and apartness I felt living there as a young, married person who desired art and writing but felt outside of it. Perhaps this is kindred to how Bourgeois felt on moving to New York, her mathematical fascination with, and alienation from, the grid of this city, the skyscrapers that informed her early sculptures, and the lines of rowhouses and tenements in packed blocks.

Though I no longer live in London, I can close my eyes and see Maman as I am back walking over the Millenium Bridge to Tate Modern – its central chimney, the immensity of the structure. To picture Maman inside the Turbine Hall again for Tate Modern’s 25th anniversary is a little scary, like encountering a spider indoors. A spider is often an unwelcome guest, even if we know they are also protective. Bourgeois’s works are largely about spatial relations: the body becoming the house, and the reverse of this; they are about both expansion and containment.

It wasn’t until the mid 1990s, that Bourgeois returned to the image of the spider and began making these massive sculptures. This has been interpreted as a turn to her mother, almost a changed spatial relation to her childhood, when so much of her earlier work was thinking through the violence of, and her identification with, her father. Although I’ve never previously made this connection, Bourgeois’s mother died when the artist was in her early twenties, as was I. It was just a year after my mother’s death when I moved to London and first encountered Maman. I say ‘the artist’, but it was only when her mother died that Bourgeois, like me, began to think about making art – almost as if that death had freed her, in a way, or done the opposite: become an obsession, a web that enclosed her.

There is a productive tension between anger and repair in the work of Louise Bourgeois. Anger is seen as destructive, violent, aggressive, and this is a mode through which she worked. Repair is seen as maternal, protective, a practice of care – to fix the damage.

‘Maman’ is a term a child would use: Mommy. The spider weaves, and when the web is destroyed, the artist has said, it doesn’t get angry; it just repairs the web. Bourgeois’s mother was also a weaver – a restorer of antique tapestries and manager of the family workshop. In Bourgeois’s memories, she both protected the child from the destruction of the father’s affairs and, through the sewing or repairing of the family, attempted to hide the damage.

With my children, I watch an online video of a spider weaving its web. How industrious it is, how fast it moves around and around. My eight-year-old knows more about spiders than I do. Their silk is stronger than steel. The web is a defensive structure. The spider eats its own web to replenish its silk supply.

The artist must do the damage, must undo, must redo, as was Bourgeois’s mantra. The web must be damaged and then repaired, but the seams should show. The image of the spiral repeats throughout Bourgeois’s work – the spider web, the cocoon, the tense coil. The spiral is emotional. It is both aggressive and vulnerable. The artist has said that she first thought of the spiral as a gesture. She remembered the weavers washing out the tapestry in the nearby river, then wringing it dry – and thought of the wringing of a neck.

In the Book of Mutter, I quote from Bourgeois’s photo essay Child Abuse 1982. The work of the artist is both destruction and repair: ‘Every day you have to abandon your past or accept it and then if you cannot accept it you become a sculptor.’

Maman was presented by the artist in 2008 and is on display in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern. Supported by LVMH.

Kate Zambreno is a writer and professor who lives in New York. Their books include Book of Mutter (2017) and Appendix Project (2019).