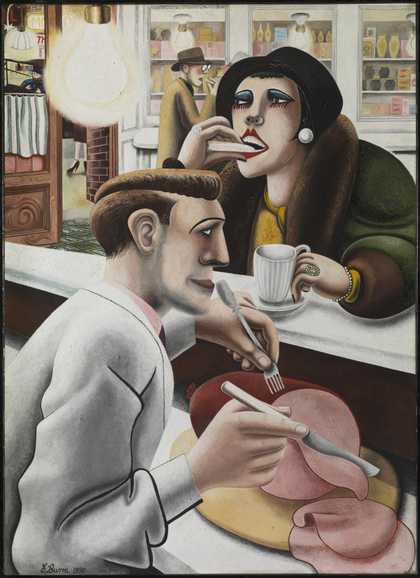

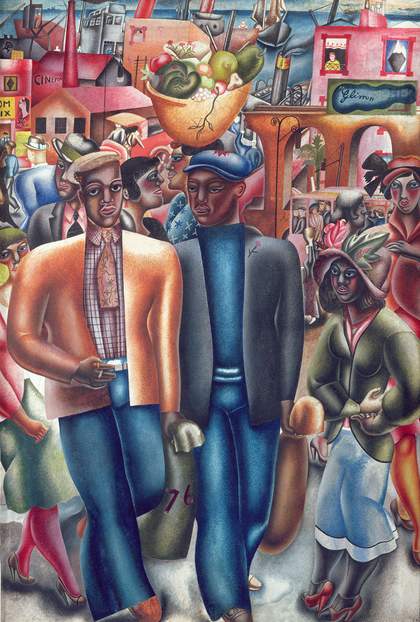

Edward Burra

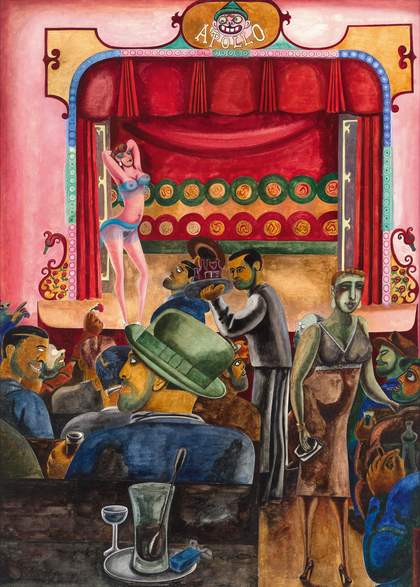

Striptease (Harlem) 1934

Estate of the artist courtesy of Lefevre Fine Art, London. Private Collection (courtesy of Eykyn Maclean Ltd, London). Photo: Kevin Candland

The British artist Edward Burra (1905–76) is renowned for his extraordinarily imaginative watercolour paintings. A master of the medium, he pushed the traditional boundaries of the form to create bold and unconventional scenes. Blending first-hand experiences and memories with a rich tapestry of sources drawn from newspapers, literature, art history, music and cinema, his often unsettling depictions of life and culture in the 20th century capture the energy, decadence and disillusionment of the age.

Born in London and raised at the family home Springfield, near Rye, East Sussex, Burra was an artist whose life and practice were shaped by his experience of chronic illness. He was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis at a young age, as well as a blood condition that caused anaemia. Encouraged by his parents to pursue art, he studied first at Chelsea Polytechnic and then the Royal College of Art, later calling painting a ‘kind of drug’ that helped to ease his pain.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Burra travelled extensively in Europe and North America, which profoundly influenced his art. During the Roaring Twenties, he painted satirical scenes of clubs, cafés and cabarets in Paris and the South of France. A passionate jazz enthusiast, he also captured the vibrant cultural entertainments of New York during the Harlem Renaissance, reflected in Striptease (Harlem) 1934 (pictured here). His fascination with the macabre also informed his interest in Mexican culture, with its rich traditions surrounding death. After witnessing the violence of the Spanish Civil War and Second World War in the 1930s and 1940s, his outlook radically changed, and his works became imbued with a darker, more uncompromising tone. Though his art explored themes shared by the surrealists, he showed little interest in formally aligning with the movement.

Burra’s creativity extended beyond painting, and in his twenties he began designing costumes and stage sets for ballet, opera and theatre productions, merging his love of performance with visual expression. In his later years, as illness limited his ability to travel abroad, he looked closer to home, depicting the British landscape and infusing scenes with a sense of unease at the impact of post-war industry on the environment. He was acutely aware of the presence of smog-belching factories and motorways that cut through Britain’s once-pristine landscape, as seen in An English Country Scene No. 2 1970.

Some 50 years after his death, Burra remains a powerful commentator on societal change and the complexities of human experience. His paintings, which fuse real scenes with fantastical elements, continue to prompt reflection on societal issues that remain relevant today. In the following pages, we’ve asked a group of contemporary artists to consider the traces of Burra’s legacy in their own creative work.

Thomas Kennedy is Curator of Modern British Art, Tate Britain.

Caroline Coon takes a trip down memory lane

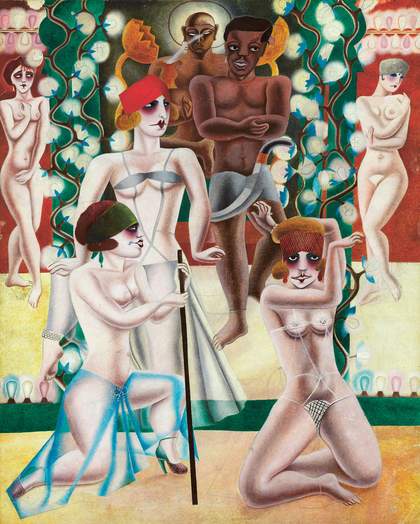

Edward Burra

Les Folies de Belleville 1928

Private Collection. © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art Ltd., London. Photo @ Tate

This exquisitely opulent painting seems to glow. It is ablaze with light – there are no shadows. As if I were sitting beside Edward Burra in that small, close theatre audience, I can see every detail from his point of view. The theatre curtain is pulled back and the stage light dazzles our eyes. The smell of greasepaint, sweat and resin wafts over us, and our excitement rises as the tableau vivant springs into life.

Burra dances our eyes back and forth as if to the rhythm of the jazz music he loved: from the shimmering pale-pink flesh of the show girls, the towers of light bulbs disguised as climbing flowers, and the swaggering male dancer with a shiny dagger in his sarong to the Buddha sitting in lotus pose whose presence overlooks and blesses the scene.

Like the performance Burra would have witnessed, Burra wanted his painting to light up our imaginations. European flapper fashion is juxtaposed with the artist’s admiration for other cultures. The kohl-eyed stunner on the right makes arm gestures associated with early 20th-century stage interpretations of ‘oriental’ dance. The composition’s complexities, meanwhile, are poised, resolved and stabilised by Burra’s classical geometry. Distance and depth are represented not by perspective but by receding proportions, the smaller figures in the background. We are convinced by this skilled performance and can join in with the applause.

To fully appreciate a painting, it is often helpful to have experience of what it represents, and my pleasure in this painting is enhanced by my own recognition. The nightlife that Burra revels in showing us was very familiar to me as a teenager. After I grew too tall for ballet, I had dreamed of being a famous Bluebell Girl at the Folies Bergère in Paris; instead, I worked as a house model for the fashion designer Norman Hartnell, at his showroom on Bruton Street in London. Just a few doors down was the Lefevre Gallery, where Burra exhibited. He had been unknown to me then, not yet an exemplary artist taught at art school. What a terrific surprise I had one day in my lunch hour!

Gazing that first time at Burra’s work, with its vivid solidity, I assumed it had been made with oil paint. On second glance, I was startled to discover that he was using mostly watercolour or gouache on paper. Until then, I’d had a fixed idea of how water- colour should look – that is watery. I held the watery technique of William Russell Flint in the highest esteem. Burra wrenched me free of such orthodoxy and showed me another way to use the medium.

Burra lays down colour with no visible brush strokes, no seeping runs or drips to draw our attention to the surface of his work and disturb his narrative vision. Perhaps he developed this style in order to keep the superb primacy of his drawing bold and distinct. He achieves luminosity and intensity of colour not by letting white paper show through a single wash of paint, but by layering colour – ever opaquer – wash after wash. Where he wants to contour a body with light, he uses his soft brush to pull the colour off the paper again. At least, this is one way I have found to achieve a Burra-esque body contour effect.

The detail in this painting evokes a power that belies its small size, like a religious icon that aids our appreciation of the fullness of existence. The way Burra passionately observes life and his ingenious conjuring of light – even his daylight is theatrical – returns me to his paintings again and again.

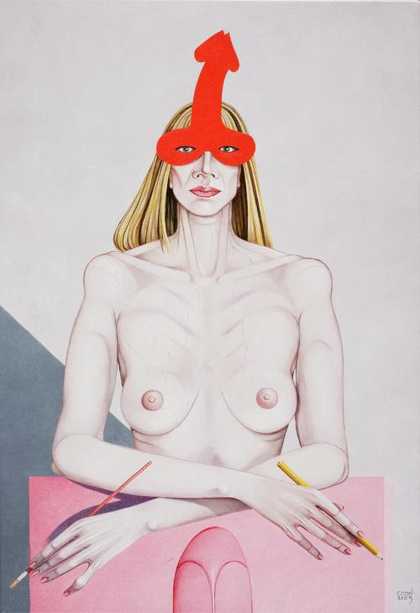

Caroline Coon is an artist, writer, political activist and a trailblazer of London’s counterculture. Her works Self in Cock Mask 2003 and Self with Delphinium Age 70 2016 were presented anonymously in 2021.

Nick Goss is drawn to a hard-boiled noir

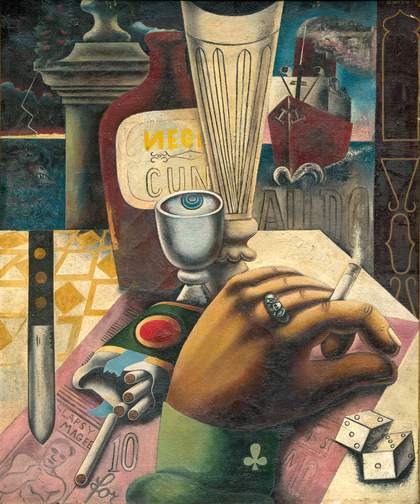

Edward Burra

The Hand 1931

Private collection. © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art, London

I've always been fascinated by the idea of the artist as an interloper, someone who’s not totally embedded in a place but is more of an observer. For instance, Edward Burra wasn’t living in Marseille when he made The Hand 1931 – he was on one of his many trips from England to the port towns of Southern France. He had so many medical issues that he could never live far from his home in East Sussex. Burra was not quite a flâneur, like the artists Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec or Walter Sickert, who sketched in bars. He would interact with people in these settings, but then go back to the studio to make his work. His was a studio-based practice, but his dreams and his mind were elsewhere. That disconnect is so interesting to me.

Although The Hand is based on one of Burra’s trips to Marseille, I love the pure stagecraft of the composition. He’s spliced together an entirely fictional psychological space. Burra’s paintings are kaleidoscopic, almost collaged. For instance, the ship that can be seen through the window – I’m certain it’s been taken from a brochure for a cruise liner or a boat trip around the harbour. Perhaps he was walking through Marseille, picked up a leaflet, and thought: ‘I’m keeping that for one of my paintings’.

The Hand is also a masterclass in ominous imagery. Central to this atmosphere are the reflections or ripples in the glass, which become an eyeball, sitting slap bang in the middle of the painting. The objects huddling around it: the bottle, the dice, the dagger, the skull-and-crossbones ring – I think this is Burra’s hand because he owned a ring just like it – all add to this sense of lawlessness. There are other hostile elements around it too: the shark-filled sea, the steam ship ploughing towards you. These objects become the figures of the work, evoking the idea that in a port or harbour – those liminal spaces – laws, even ideas are fluid; genders are fluid. Everything is up for grabs, and everything is dangerous.

I get a sense that Burra, like Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon or Sickert, was attracted to the darker underside of life. He thought that this was where the real art could be found. His paintings feel like the beginning of a hard-boiled film noir, or a Graham Greene or William Burroughs novel where all hell is about to break loose.

As in my favourite Max Beckmann or Giorgio de Chirico paintings, there is something quite jarring about the composition of this painting. Everything is arranged to withhold information from the viewer and convey the sense that we know only a small fragment of the story. Your eye can never settle. You might start on the hand, and then your eye roves around to the ring, to the cigarette, before the smoke takes you up to this mysterious boat. You’re being asked to mull over the relationship between those items, but you’re not getting any answers. The uncanny reigns supreme. In paintings, the hints, the atmosphere, interest me most. That’s why The Hand stands out; there’s so much to talk about, but it remains a mystery.

Burra’s art, particularly this painting, has influenced my own. Various motifs of laden tables appear in my work and I have also used a silkscreen technique to print images within the paintings, a bit like collage. I also enjoy working with the weird perspectives that Burra uses – the flatness of the dice versus the exquisite contouring of the hand, for example.

Before looking at Burra’s work, I was obsessed with having lots of space in my paintings, but I’ve since been inspired by the way in which Burra squeezes in these tantalizing architectural details. In The Hand, even the smallest scrap of the scene – for instance the top right corner – contains an amazing tableau that would make a great painting in itself. He has no right to situate these details so close to the edge of his work! There is so much life in Burra’s work – it fights for every last inch of paper.

Nick Goss is a painter who lives in London.

Louis Fratino looks on, lustily

Edward Burra

Three Sailors at the Bar 1930

Private collection, courtesy of Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert. © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art Ltd., London. Photo: Lefevre Fine Art Ltd., London / Bridgeman Images

The first thing I see when I look at this painting is the way the trousers hug the sailor’s ass. It reminds me of Charles Demuth’s watercolours of sailors, as well as paintings by Paul Cadmus. While we don’t know much for certain about Edward Burra’s sexuality, this lusty way of looking at everything in the world, men included, is important to anyone interested in queer modernism.

Burra was someone who seemed relatively unfazed by the reality of queer people in his own time, unlike some of the better-known modernist painters who wouldn’t have been as willing to represent queerness. He seemed to get a kick out of humanity, regarding it with an openness that clearly includes the idea of queer sexuality. I mean, nobody renders a sailor’s ass like that unless they’re well aware of what it means.

In my own approach to painting, the most mundane things can offer the most exciting viewing – it’s just a case of taking the time to really look. In this painting, Burra does just that. He invests as much in the sculptural hand turning on the coffee machine as he does in the weird rooster shapes sitting above it or in the reflection of the person’s face in the mirror behind the bar. I think of this as a democratic way of looking, where every aspect of what’s seen is represented equally. While the human body can often dominate a painting, in Burra’s world a tiny martini glass or the surface of a table can be just as important. I love that way of looking: where everyone comes turned on, and everything has the potential to say something or give emotional resonance.

In Three Sailors at the Bar 1930, I enjoy the way that the pole in the middle ground bisects the barman’s face, and how the backs of two of the figures’ heads are treated almost identically. Compositionally, Burra is great at capturing the sensation of our impulse to look at people despite not knowing them – the fragmentary nature of people passing you by.

I also love noticing which elements in Burra’s work are made more complicated versus which are simplified: the almost tubular forms of the sailors’ limbs, for example, are not naturalistic but stylised, in contrast to the obsessively rendered grate of the coffee machine. This style makes me think of illustration (which I studied before focusing on painting), a sense reinforced by the fact that this is a watercolour, a medium often associated with illustration. Burra’s watercolour, though, is so impossibly rich that it could be oil painting.

Burra has such a weird eye, which I think corresponds to how memory operates. Looking at the table in the foreground, I realise it has no legs. It’s an impossible table. But it makes perfect sense from the perspective of memory. I work from memory too, and it’s as if Burra is saying: ‘That’s not what I remember or care about, so I’m not going to try to awkwardly fit in the legs.’ Rather than sitting in a café, drawing from life, objects become transformed in Burra’s world.

I’m just starting a painting of the New York subway that borrows from Burra’s The Torturers c.1935, which is itself an invented painting, full of machinery and sexy, terrifying figures in masks. I’m attracted to it because it’s a foil to my own work, which often has a softness to it. I want to push my relationship with Burra, because, while his view of the world is playful, it also accommodates terror and horror – things that don’t come naturally to me but are truths about the world, especially now. By getting closer to Burra, I am trying to understand how to maintain a playful, joyful view of the world without turning from the reality that it can be violent, tortured or neglected. I think that I’ll inevitably fail – I’m a different artist, a different person – but hopefully, for having tried, I’ll learn something from him.

Louis Fratino is a painter who lives in New York.

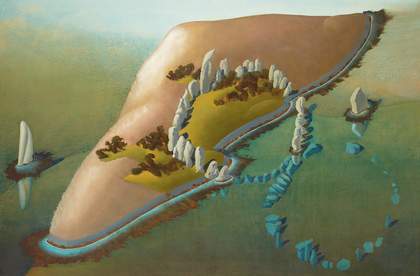

Tanoa Sasraku mourns the plunder of the pastoral

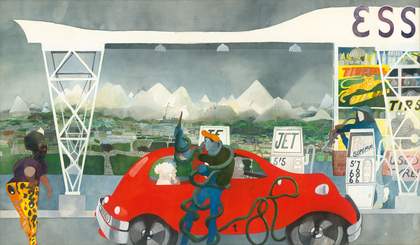

Edward Burra

Cornish Clay Mines 1970

Private Collection. Estate of the artist courtesy of Lefevre Fine Art, London

In this eerie watercolour by Edward Burra, zombified human figures and calcified hills – the spoil tips from mines – appear drained of their lifeforce in the wake of a petrol-fed, luminous red car. In the foreground, a young man wields an engorged petrol hose, which constricts his neck and limbs like a predatory snake. With vacant obedience, he continues his car-feeding task. I am reminded of videos of ants infected with the parasitic cordyceps fungus, otherwise known as ‘zombie-ant’ fungus. The female figure on the left of the composition exhibits a similar inertia, and her gaze is inexorably drawn towards the car, its red luminosity reflected across the surface of her glasses.

There are references to fashion trends in this picture that intrigue me, especially as they intersect with the intergenerational nature of the figures depicted: the elderly figures inside the car sport perms, while the hose-wielding man wears a baseball cap, brim upturned. I feel that Burra is nodding to the rapid acceleration of Western popular culture as a result of oil production and consumption. For example, the symbol of the gasoline-powered car in Hollywood cinema is highly suggestive of authority, sexuality and freedom, while the development of plastic-based products has broadened the scope of advertising through innovations in packaging, paint and ink production. Burra suggests that neither the elderly nor the young are spared the trappings of a society driven by the industrialisation of the pastoral landscape for these ends.

Compositionally, there is an odd inverse reading of this work, with the upright support structures of the petrol station resembling oil derricks, as if the darkening sky is also fair game for plunder. Some reprieve seems to be offered by a protective, interlocking system of dry-stone walls containing green fields and farm buildings – an agricultural chain in resistance.

I appreciate that Burra has chosen to approach these themes of heavy industry via the medium of watercolour on paper. While the picture is vivid, there is a lightness of touch that creates an atmosphere of impermanence. Lately, I have found the notion of impermanence useful to return to in the studio as I handle the subject matter of oil, territory and expansion, and experiment with novel processes and materials far more unstable than the ancient mineral pigments that I have relied on in previous bodies of work.

Tanoa Sasraku is an artist who lives in Glasgow.

Mohammed Z. Rahman discovers an earnest spirit

Edward Burra

Market Day 1926

Estate of the artist courtesy of Lefevre Fine Art, London. Photo: © Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

Market Day 1926 conjures a feeling of nostalgia towards the multicultural metropolis of London: the bustle of Green Street, Kilburn High Road, Brixton Market, Southall and Ridley Road. The figures balancing fruit and toting bags make me think of going to Walthamstow Market to help my ma with the shopping, wheeling her granny trolley through the hubbub of the stalls twittering around us. Through Burra’s painting, I remember the market as a theatre of desire – the emotion is so stark in his figures’ stares that their eyelids are heavy with it.

And yet Market Day was painted as a fantastic premonition of Edward Burra’s visits to multicultural port towns in the South of France. He first travelled to the region in 1927, a year after this painting was made. Living a life marked by defiance against the loneliness of chronic illness, Burra comes across as an earnest spirit seeking connection through the visual. His watercolour of nowhere in particular bursts with wanderlust.

There is something convincing about Burra’s vision. It makes the intimacy of the scene, in all its sprawling variety of people and place, feel heartfelt in a way that moves beyond the voyeuristic. Though ultimately a fabulation, the opacity and saturation that Burra brings to the watercolour make Market Day feel at once concrete and magical. I strive for this in my own work. It’s in the headiness of the amount of grey he mixes in, which is then perfectly counterbalanced by the graceful flourishes in his forms – in the dainty hands blossoming at the end of pillar-like limbs. It’s in the illusion he creates by using the same contrast of values in the background and foreground, so that everything is happening all at once.

I should say that artworks like this pull up a form of instinctive ‘double consciousness’ – sociologist W.E.B.Du Bois’s idea that in a world where Blackness is othered, the world is experienced twice over: first through one’s own eyes, and again through the perspective of a White society. I’ve found this framework useful to articulate my experience as a working-class Bengali Muslim in the UK. Paintings like Market Day make me anticipate the gaze of upper-middle-class Whiteness and rehearse my fluency in otherness. This reflex bolsters flimsy social fictions that, in their instability, are in constant need of reaffirmation. It’s bottomless busywork. These days I prefer to look at things in search of solidarities.

With the knowledge of our differences, Burra still manages to speak to my experience of the vibrant worlds of queers and migrants as being both camp and proletarian in non-paradoxical ways. I identify strangely with the subjects in Burra’s paintings; they’re people like me. In this, Market Day makes me marvel at how paintings can speak across centuries as a lingua franca between dreams and lived history. That’s what excites me about any medium: its potential to sow connection.

Mohammed Z. Rahman is an artist who lives in London. His paintings The Lovers 2024 and The Spaghetti House 2024 were purchased with funds provided by the 2024 Frieze Tate Fund supported by Endeavor to benefit the Tate collection in 2025.

John Stezaker goes on a final journey

Edward Burra

Near Whitby, Yorkshire 1972

Ingram Collection of Modern British Art. © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art Ltd., London Photo: Lefevre Fine Art Ltd., London / Bridgeman Images

What has always fascinated me about Edward Burra’s works is their unpredictable ambiguity. It’s never clear where he’s coming from. A seemingly alluring scene of erotic display, when probed more deeply, reveals disturbing, sometimes unsettling, undercurrents. Paintings addressed to the horrors of contemporary war also contain uneasy suggestions of homoerotic masochism. His monsters transform into sexual fetishes and vice versa, and our diametrically opposed responses to the subjects of his paintings are made to co-exist and intermingle uncomfortably. One senses that he neither has, nor wants, conscious control over the outcome of his paintings or the way in which a series evolves. He seems surprised by where they take him (and perhaps what they tell him about himself). That’s why everything he does seems flawed. His paintings are never quite what they seem.

However, this falling short, this twinge of something being awry, out of place or inappropriate, is key to the power of his work. One senses that his own unknowability is the flaw that interferes with the completion and unity of the image. Confronted first- hand by the contemporary atrocities of the Spanish Civil War, it seems grotesque to stage his representations of war as figures from Hispanic legend in full period dress. But somehow it is in this intermingling of horror and picturesque allure that something of the unreality of the war is communicated – the way that distant medieval images of execution and torture can arrive on our doorsteps. These paintings are not so much confrontations with the Spanish Civil War as they are barricades, or attempts to find a distance from these events. Burra’s investment seems to be in the vertiginous space between (the body and the world beyond). What he clings to, in all his work, is depth, pictorial space, and its ability to create a space for his imaginary escape.

In Burra’s late road paintings, he seems to hone in on a desire to see into the beyond. He had previously shown only sporadic interest in the rural landscape in which he lived, unlike his painter friends, such as the brothers Paul and John Nash, whose work centred on the East Sussex landscape. Burra’s late awakening to the English landscape was expressed through images of its violation: brightly coloured monster diggers with cartoon faces cutting through the gently rolling landscape of the Downs.

The artist’s first focus was on the disturbing spectacle of the pastoral being obliterated in its transformation into a gigantic building site for the creation of roads and motorways. But slowly these vertical incisions, cutting through the horizontality of the landscape, became a new point of fascination – as magical intrusions from another dimension. Burra finds a reconciliation in these fissures, painting scenes recalled from drives in the Yorkshire Dales. Delivered of the central focus of the driver’s vigilant vision, Burra, as a passenger, has reserved the right to see rather than look. In Near Whitby, Yorkshire 1972, the road belongs to a different dimension from the static world through which it winds. One senses that it is an image of leaving the world behind, a final journey, and, at last, resolution in a flawless perfection.

John Stezaker is an artist who lives in London and St Leonards-on-Sea. His artworks Third Person 1988–9 and Untitled 1989 were purchased in 2007 and are on display in No Such Thing as Society at Tate Britain.

Edward Burra, at Tate Britain, until 19 October.

In partnership with Lockton. With additional support from the Edward Burra Exhibition Supporters Circle and Tate Members. Curated by Thomas Kennedy, Curator, Modern British Art, Tate Britain with Eliza Spindel, Assistant Curator, Tate Britain.