Josef Koudelka

Ireland (1972)

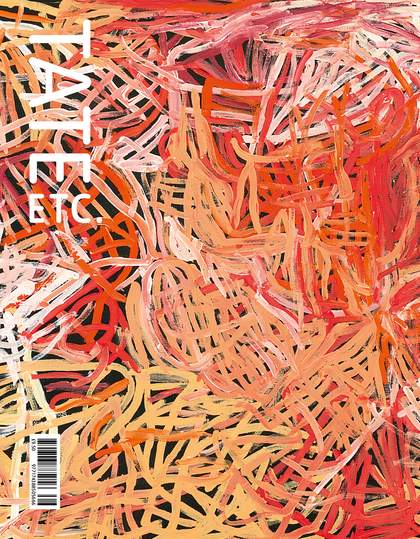

Tate

© Josef Koudelka / MAGNUM Photos, Courtesy of the Josef Koudelka Foundation

I write for now from that place that is before the camera, where what is ‘taken’ by the photograph is located. I first saw the photograph Ireland 1972 in an art gallery in Manchester in 1984. Two of the men in it are my kin. The younger man on the right is my first cousin, Seán Joyce (Seán Seoighe) and on the left is Paddy Kenny (Pádraig Ó Cionnaith), the husband of Sean’s sister. The man in the middle is a neighbour.

They are kneeling on the summit of Croagh Patrick in Ireland’s far west, the holy mountain which has been a place of pilgrimage for around 1,500 years. Local people call it simply ‘the Reek’, from the Irish-English ‘stack’ or ‘pile’. The three men would have walked to and from the Reek, as well as climbing it – a walk of around 40 miles in total. Many ascend the mountain barefoot. Some process on their knees near the summit. The three men in the picture come from Joyce Country, Dúiche Sheoighe – south of Croagh Patrick and to the immediate north of Connemara.

Over half a century after the photo was taken, I asked Josef Koudelka about the circumstances around its taking. He told me that he did not dare speak to the men or disturb them, as it was a very special moment. So it is: these men are in an act of religious devotion. Josef had been kneeling not too far away from them in another act of devotion – that being to his vocation, his ‘calling’ of photography.

Josef Koudelka

Prague, August 1968

© Josef Koudelka/Magnum Photos. Courtesy of the Josef Koudelka Foundation

What does it benefit the viewer, who may see the 28 Koudelka photographs on display at Tate Modern, to know something of the history of one of them? Perhaps not a lot. As publisher and curator Robert Delpire has written of Josef’s achievement: ‘He doesn’t give form to what exists. Nothing exists before him’. Josef has compared his own photography to a form of theatre for which the play has not been written. And, as French poet and essayist Paul Valéry once remarked, ‘photography encourages us to stop trying to describe what can clearly describe itself.

So we might, with justice, say that Josef is not a documentarian, least of all a historian. He does not ‘report’ on what he sees – perhaps save for his great Prague invasion photos of 1968. Josef Koudelka does not wish, as he has said in the past, to define the culture of others. He tells me, when we talk in April 2025, that there is no criticism in his pictures, that he is a visual person – knowledge coming through the eyes.

Correspondingly, the publicity for this exhibition says that when placed together the photos ‘reveal a timeless narrative of societal and personal transformation’. The photos are therefore ‘outside’ of time. But how can this be so? How can transformation be outside time? Clearly, there is something going on with time in these images. Just as the people in them are caught in a precise moment of time, they do, indeed, also seem to be outside of it. All photographs negotiate time in similar fashion and produce this effect: one frozen moment of time endlessly prolonged – that which was full of time is now outside time, but only outside time because, in the same moment, it is full of it. Josef’s photographs powerfully accentuate this double effect.

Josef Koudelka

Wales (1974)

Tate

© Josef Koudelka / MAGNUM Photos, Courtesy of the Josef Koudelka Foundation

For instance, in Ireland 1972 the three kneeling men each lean on a pilgrim’s stick in a different way, time’s plenitude apparent. The strong echo of Christ’s crucifixion gives the human trio an epic, monumental quality – as if they are outside time. But the sight of the short skirt worn by the woman in the background reminds us that it is, indeed, 1972. The three men are ‘timed’ too: their dark suits and white shirts a token of an old way of worship – like the old way of life in its totality, then beginning to retreat across Europe.

In Koudelka’s series Exiles (1988) and Gypsies (1962–71) there is indeed a strong sense of a world on the turn. What drew us together was my consideration of his work in my book on the end of peasant Europe. Josef has remarked that he is always drawn to what is ending, what will soon no longer exist. I tried to draw him out on the matter of what motivates his interest in these worlds at five minutes to midnight and his answer was simply: ‘I think I was born like that.’

The titles of Josef’s photographs bear the year and country in which they were taken, and sometimes the place. You know where you are in time, even as the images entirely retain their mystery, and sometimes their menace, as in Wales 1974. Though, even here, some viewers will recognise the face from the TV, a sportscaster, as was then the term, a man called ‘Dickie’ Davies.

Then there is the extraordinary picture of the man showing a photograph of himself alongside a giant roundel bearing a relief of Klement Gottwald, Czechoslovakia, Slovakia, Rakasy 1966. Gottwald was a key figure in the Communist takeover of Czechoslovakia in 1948. By 1966 he had been dead 13 years.

Josef Koudelka

France (1976)

Tate

© Josef Koudelka / MAGNUM Photos, Courtesy of the Josef Koudelka Foundation

There is France 1976, in which the means of daily life’s sustenance are laid out on a newspaper – the image a sort of treatise on time, so rich are its possibilities. The Gypsies images are rooted in the precise times of the poses and bold faces of the individuals photographed.

The mystery of these images concerns the mystery of time itself. They probe time, occupying the ‘in-between’ of time, and the interstices of different times. To me, now writing as a historian, I think of Josef as following a not dissimilar trade to my own. For what we know as history ‘proper’ is always made between times, as, rooted in the present, we negotiate a past that is not, as we commonly think, unilinear but multilinear. The past is not the action of the arrow of time pointing forever forward, but more like the flames of a brazier, constantly changing, reaching up and then falling low. Fire and water. Time is like a river on which we move, but the banks through which the river flows are themselves in constant movement too.

Koudelka and I spoke together as old men. I am seven years his junior. We talked about the people in the photos, about how times have changed, but also about how those of an older time were ‘substantial’, had gravity and presence. For all his tribulations with his home country, Josef says he is lucky to have been born in Czechoslovakia. We both pay a sort of homage to the times that have been. We were born like that. His final words to me are ‘Keep on dancing’.

A selection of 28 photographs by Josef Koudelka are on display in Artist and Society at Tate Modern. Ireland 1972, Wales 1974 and Czechoslovakia 1968 were purchased with funds provided by the Photography Acquisitions Committee in 2023; Prague, August 1968 was purchased with funds provided by Robert Runták in 2023; Ireland 1976 and France 1976 were presented by the artist in 2023.

Patrick Joyce is Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Manchester. He has written about photographs in Going to My Father’s House: A History of My Times (2021) and Remembering Peasants: A Personal History of a Vanished World (2024). He is working on a book provisionally titled Where the Past Goes: Time and Memory in Darkened Years.