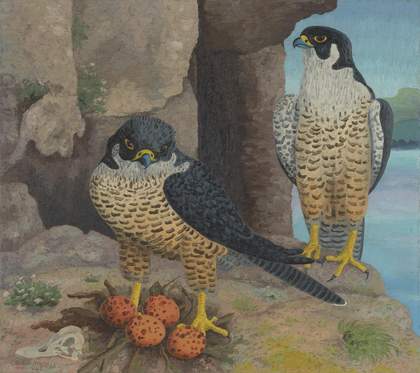

Sir Cedric Morris, Bt

Peregrine Falcons (1942)

Tate

If we had to pick one bird to stand as a symbol of hope for human relations with the living world, then the peregrine would probably be first choice. Exceeded only by our species, this falcon – which is also the fastest flying bird on Earth – is the world’s most widespread terrestrial predator, breeding on all seven continents.

Yet in the 1950s, just a few years after British artist Cedric Morris completed his painting of a breeding pair, the peregrine nosedived into population collapse. That the bird was judged to be at risk of global extinction now seems almost unbelievable, especially given its near-total resurrection. In Britain today, there have possibly never been more peregrines since the Middle Ages.

What began this extraordinary story of hope was the discovery by British naturalist Derek Ratcliffe that a build-up of agrochemicals, such as DDT, in the birds’ body fats was causing them to lay eggs with unnaturally thin shells. The parents then inadvertently broke them as they brooded. This one small part of avian ecology was having massive ramifications, not just for this falcon, but for thousands of bird and animal species equally affected by such poisoning. The campaign to halt the use of these products, dramatised in Rachel Carson’s epoch-making book Silent Spring (1962), gave rise to the environmental movement we know today.

In Morris’s rather idyllic family portrait of a peregrine couple almost proudly surveying their four, jewel-like eggs on a cliff ledge, all of this turmoil seems far into the future. Yet the painting dates from 1942, a fact we cannot possibly ignore. This was, after all, the year of Stalingrad and El Alamein, the hinge battles on which the Second World War and democratic fortunes turned.

Could there be some latent symbolism in Morris’s almost decorative portrayal of what is, in truth, a formidable raptor? Perhaps he was telling us that in all parts of Nature – whether the garden flowers he cherished or in a bullet-like bird of prey – there is a permanent beauty to which his own generation would one day return. Whatever humankind might do to itself, the living world would help to restore us to peace and harmony, just as the peregrine would later emerge from its own crisis.

There are, in truth, one or two errors in the work. Contrary to the painting’s portrayal of a little platform of twiglets, peregrines bring no nest material to their ledge. Yet perhaps a little botanical invention can be permitted to a plantsman and artist as great as Sir Cedric Morris?

Peregrine Falcons was bequeathed by Miss Nancy Morris, the artist’s sister, in 1988 and is included in the new collection display Birds at Tate Britain. From July to February, the chimneys at Tate Modern are one of the most reliable places to spot peregrines in London.

Mark Cocker is an author and naturalist. His latest book is One Midsummer’s Day, published by Jonathan Cape.