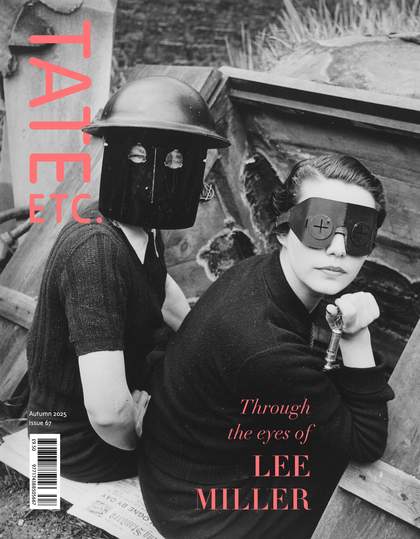

Emily Kam Kngwarray

Ankerr (Emu) 1989

© Emily Kam Kngwarray / Copyright Agency. Licensed by DACS 2025. Image courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria, Naarm/Narrm/Melbourne. Photo: Predrag Cancar

Emily Kam Kngwarray (c.1914–1996) is perhaps one of Australia’s greatest artists. Born around 1914 in the Sandover region of Central Australia, her life spanned some of the most dramatic changes that Aboriginal peoples from these remote regions faced in the 20th century. Kngwarray grew up speaking the eastern variety of a language called Anmatyerr. For her, English was a foreign language, spoken by white settlers who took over Ancestral Aboriginal lands, introduced sheep and cattle, built fences, and sank bores to access water.

Kngwarray spoke little English and during her lifetime her own language remained largely unwritten. So, at a time when we are seeking to share Kngwarray’s art and worldview with wide audiences through major presentations of her work at institutions such as the National Gallery of Australia and Tate Modern, how should the art world represent the language she spoke, and the ideas that were important to her?

Emily Kam Kngwarray and Jennifer Green recording songs and oral histories for CAAMA radio, Atnarar (Soakage Bore), 1983

Photo © Jeannie Devitt, 2025

Emily Kam Kngwarray is known by three names, and these differ in terms of their time-depth, provenance and social functions. Kngwarray grew up in the bush, and encounters with whitefellers were rare during her childhood. For at least the first few decades of her life she would not have answered to the name ‘Emily’, which first appears in records from the 1950s and 1960s. Her first name was probably the last she acquired. We don’t know who chose that name, but chances are it was not her parents. Station owners, police and other administrators gave Aboriginal people whitefeller names, partly to assist in frontier accounting that enabled the flow of rations in exchange for Aboriginal labour on pastoral properties. Such names depended very much on the nature of encounters with settler colonial society. Some names, such as Stalin, Hitler, Flourbag or Goggle Eye were insulting or derogatory. As so eloquently highlighted in Kamilaroi/Bigambul artist Archie Moore’s award-winning installation in the 60th Venice Biennale, some people were known, even in official records, by names that were mocking, offensive or diminutive. ‘Emily’ was a benign choice, but she might not have been so lucky. Kngwarray learnt to write her ‘first’ name in the women’s literacy classes at Utopia Station in 1977, although she seldom signed her artworks. If she did so it was by first name only.

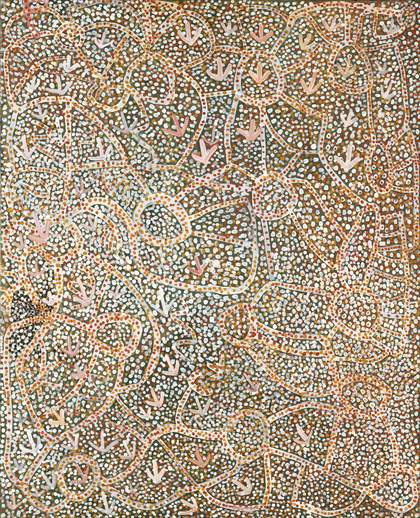

Her bush name, Kam, is the Anmatyerr word for the seeds and seedpods of anwerlarr, the pencil yam. This plant was of particular significance to Kngwarray, and it comes from her Country, a place called Alhalker. The name was given to her by senior relatives from there. It is often the case that detailed and rich vocabulary coalesces around topics of great importance, indicative of ecological knowledge held over countless generations. Kngwarray’s statement, ‘I am Kam’, reflects the personal and ceremonial significance of this name. She often painted the pencil yam – its twining vines with their yellow pea-like flowers, underground root systems and the edible subterranean seedpods that were her namesake.

Alhalkerarl anwernekakerrenh. Anwerlarr. Atyenh arrernek mern, mern ayengarl inewelhek – mern annga yanh-lkwer ayengarl inewelhekek. Kam arreyn ap ra. Kam. An mern anwerlarr-warl inewelhek. Me Kam now. Mern anwerlarr mer nhenh-areny-kenh aylernekakenh. Anwerlarr ra. Arnkarrel ap ra antyem, arnkarr alakenh apety-alperleng. Painting anem renh tha do-emilek. Mer anem tha atyenh urlertarrp arrernepernem. Mern kamarl anganek ra. That’s all.

Emily Kam Kngwarray

Kam 1991

© Emily Kam Kngwarray / Copyright Agency. Licensed by DACS 2025. Image courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria, Naarm/Narrm/Melbourne. Photo: Predrag Cancar

Alhalker Country is ours – so is the anwerlarr yam. I paint my plant, the one I am named after – those seeds I am named after. Kam is its name. Kam. I am named after the anwerlarr plant. I am Kam! The pencil yam grows in our Country – it belongs to us – the anwerlarr yam. They are found growing up along the creek banks. That’s what I painted. I keep on painting the place that belongs to me – I never change from painting that place. The seeds and seedpods of the pencil yam originated there. That’s all.

EMILY KAM KNGWARRAY, 1992

The skin name ‘Kngwarray’ is shared by many hundreds of Anmatyerr people who call Central Australia home, as well as by perhaps thousands from neighbouring language groups who also have this name (spelt slightly differently but sounding very similar) in their kinship systems. Some older spellings of this name, such as Ngwarai, Warai, Agnarai, and Ngarai appear in records from pastoral properties such as Utopia or MacDonald Downs. These different spellings show how hard it was for non-Indigenous people to get their tongues around words in the local Aboriginal languages and the difficulty in using the conventions of English spelling to represent their sounds. Standardisation would have been possible, if there had been a dictionary, but at that time there wasn’t one.

In some Aboriginal communities, including Anmatyerr ones, saying the personal names of the deceased out loud is prohibited for a time after their passing. As a mark of respect substitute names such as kwementyay are used instead. There is no evidence that this rule ever applied to skin names, which continue to be used. In 1995 Kngwarray authorised the use of her personal names posthumously, paving the way for major exhibitions that followed soon after.

The Central and Eastern Anmatyerr to English Dictionary was published in 2010, over a decade after Kngwarray’s death in 1996. The dictionary involved the work of more than 100 Anmatyerr people, including Elders who are acknowledged as language experts, and younger literate generations with skills to make informed decisions about the spelling of their own language. Kngwarray is credited in the opening pages of the dictionary, although during the research for the publication she was busy painting, and had little spare time for language work. Nevertheless, the deep cultural knowledge that Kngwarray and others like her held is reflected in the publication. Part of the reason for making dictionaries of Australia’s many First Nations languages is to create sustainable records of languages for future generations.

Nhenhan amer atyenh-areny-antey, alharl rnternirrekarl aknganek-antey, nhanyem. Alhalker kwerel. Alanh anem ayenh arreng-arrengel alharl rnternek nhenh. Nhenhel ayengarl kwerel alhepalhem tha ingkwerneperneman.

Emily Kam Kngwarray

My Country 1993

© Emily Kam Kngwarray / Copyright Agency. Licensed by DACS 2025. Image courtesy of Milani Gallery, Meanjin/Brisbane

This is my Country here, and the practice of piercing the nose originated there in the Dreaming. At Alhalker. That’s why my grandfather pierced my nose here. I keep following that Country, and that’s what I keep on painting.

EMILY KAM KNGWARRAY, 1990

Decisions about spelling were made at meetings held in homeland communities and regional centres. For example, in the 1990s, speakers of Anmatyerr and of the neighbouring language Alyawarr decided against using ‘e’ on the ends of words in their languages. Linguists working on dictionaries followed community instructions and respected the decisions made. In practice this means that some words that sound very similar across large regions of Central Australia have slightly different spellings, depending on the language group. Thus, the Anmatyerr skin name ‘Kngwarray’ (or ‘Ngwarray’) corresponds to Kngwarrey in Alyawarr, and Kngwarraye in Kaytetye and in Eastern and Central Arrernte.

The historical processes underpinning transitions from oral traditions to written forms, and the ongoing interdependencies between them, are complex. Written forms of Australian Aboriginal languages are relatively recent, and in some communities, there are still debates about spelling systems. The English language also went through many changes with regard to the spelling of words, beginning almost 1,500 years ago and accelerated by the invention of the printing press and increases in community literacy. Standardisation of English spelling only took hold with the publication of the first large dictionaries in the 18th century. This left us with many inconsistencies: consider the numerous ways to pronounce ‘ough’ in the words ‘bough’, ‘enough’, ‘through’, ‘cough’, ‘ought’ etc. In contrast, and driven by advances in scientific understandings of the sound systems of languages, modern spellings of Aboriginal languages are generally quite consistent, with alphabetic letters, or groups of letters, representing particular sounds. It is a misconception to think that words in Aboriginal languages should be spelled using English spelling ‘rules’, or simply ‘the way they sound in English’. Aboriginal languages have sounds that are not found in English. Variations in the spellings of English personal names are also common. Take the name ‘Shakespeare’. In both literary and non-literary contexts it had many iterations, and even one without a final ‘e’! Again, there is no evidence that minor variations in spelling affected pronunciation.

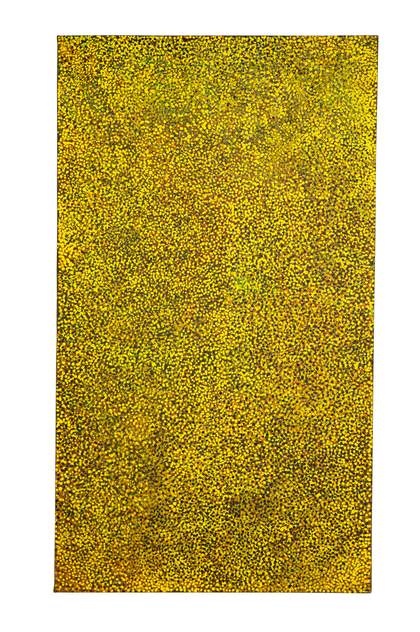

Alyatywereng anem utnherretyel utnherretyel. Awerrkerreynetyel awerrkerreynetyel ntang anem athawatherretyel. Kel arntap anem iltyem. Apert-atwerrem apert-atwerrem alyerel. Apwertel apert-atwem apert-atwem. Athetyel athetyel athemel arlkwerretyel.

Emily Kam Kngwarray

Ntang Altyerr (Seeds of Abundance) 1990

© Emily Kam Kngwarray / Copyright Agency. Licensed by DACS 2025. Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Australia’s digital team

Then we pick the woollybutt grass seeds. Rubbing the grass together to release the seeds before grinding them. Then cutting bark to make a container. Crushing the seeds with the grinding stone. Crushing the seeds with a rock. Grinding the seeds and eating the paste.

EMILY KAM KNGWARRAY, 1983

The curatorial teams for the recent exhibitions, led by Aboriginal women, have taken a respectful and consistent approach to language content, validated by extensive consultation with Kngwarray’s family and the Utopia Art Centre. The names of people, places, plants and animals are written according to the conventions of the Anmatyerr dictionary, which remains the most comprehensive source for information about Kngwarray’s language. Idiosyncratic spellings of the names of Kngwarray’s artworks were corrected so that the minimal information such titles convey becomes slightly more informative. Decoding outdated spellings can lead to new understandings of the artist’s works. Either the artist’s skin name, Kngwarray, or her three names are used in supporting material and public forums. Despite this there are still some, including those who never knew Kngwarray, who refer to her by English first name only, denoting a false sense of insider status or familiarity with the artist. Do we routinely call Klimt ‘Gustav’ or Monet ‘Claude’?

There have been some objections to the absence of the ‘e’ that was, for a short time, written on the end of the Anmatyerr words ‘Kam’ and ‘Kngwarray’. However, Kngwarray herself would not have had opinions about spelling. Like most of her generation, who grew up in the bush long before whitefeller schooling, she did not read written words. For them, what was spoken and heard was important – the spelling of words they never wrote themselves was not an issue. Small changes to spelling do not change the way words sound or what they signify, and spelling-anxiety takes attention away from more important issues. Orthographic housekeeping should be standard practice.

Jennifer Green, Pansy Sandover, Lily Kngwarrey Sandover, Andrew Sandover, Emily Kam Kngwarray, Betty Mpetyan, Julie Sandover and Rosemary Petyarr at a bush picnic, Utopia, 1977

Photo © Toly Sawenko, 2025

The most exciting part of the language-related content in the Emily Kam Kngwarray exhibition and its accompanying publication are reflections of the viewpoints of Kngwarray and of her descendants through their own first language. This is a matter of dignity and ownership, but at the same time it is a gift. Providing bilingual texts derived from oral accounts not only pays homage to these first languages – it also allows scrutiny of the choices made in translation. Understandings of the significance of what Kngwarray identified as the central themes of her works – kam (pencil yam), intekw (fan-flower), alyatywereng (woollybutt grass), ankerr (emu) and awely (women’s ceremonies) – are broadened by attention to details that are embedded in the Anmatyerr language. While such details do not explain the extraordinary power of her artworks, this background knowledge goes some way towards recognition of their rich cultural origins.

Annga pweng-irremel ntwa arem innga move-irrerl-anem, painting ra. Innga one-arl ap ran, alive-arl arraty mpwarenh. Angartewam angart-iwelherl-anem painting renh, ra anem arem renh inngapeny. ‘Eh nthakenh anem move-irretyel kwenh?’ Mer ilkwel change-irretyel colour, an move-irrerl-anem paint ra colour. Mer ilkwa nhak angart-iwelhetyel, painting nhakarl angart-iwelhetyel arrpem. That’s why arelh ampwa ra famous anem.

If you close your eyes and imagine the paintings in your mind’s eye, you will really see how they transform. They are real, and what Kngwarray painted is true and alive. The paintings keep on changing, and you see that how alive they are. You might wonder, ‘Hey, how come these paintings are changing?’ That powerful Country changes colour, just like the paintings do. That Country transforms itself, and the paintings do as well. That’s why the old woman is famous.

Jedda Kngwarray Purvis and Josie Petyarr Kunoth, June 2023, translated by Jennifer Green

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern, until 11 January 2026.

Dr Jennifer Green is a linguist and an authority on Aboriginal languages, cultural history, and visual arts from Central Australia. She met Emily Kam Kngwarray at Utopia Station and established the arts programmes there. She was the compiler of the Anmatyerr dictionary and worked closely with the curatorial teams on Emily Kam Kngwarray.

Presented in The Eyal Ofer Galleries. In partnership with the National Gallery of Australia and Wesfarmers Arts. Further lead support from Fondation Opale. With additional support from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Also supported by the Emily Kam Kngwarray Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons, Tate Americas Foundation, National Gallery of Australia Foundation and Tate Members. Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor.