Reginald Brundrit

Fresh Air Stubbs (c.1938)

Tate

Last September, I visited the Tate Store in Bermondsey, having arranged to view a portrait painted nearly a century ago by the artist Reginald Brundrit. No signage tells of the purpose of the site. Entering the large complex of modern buildings via a remotely operated gate, I felt like a spy infiltrating the MI5 offices.

Once inside, I was led to my requested picture, passing several other recently uncrated paintings on the way, including a George Stubbs racehorse and an abstract painting by Joan Miró. Brundrit’s portrait was in hallowed company. Suddenly, there it was: Fresh Air Stubbs c.1938. This was a special, even cathartic, moment in my life – because I believe the subject of this painting to be my grandfather, whom I never knew.

William Henry (known as ‘Fresh Air’) Stubbs was, according to a letter sent by Brundrit to the Tate Gallery, a ‘sporting innkeeper well known in upper Wharfedale’ in the Yorkshire Dales. Brundrit’s portrait is highly detailed and realistic, down to the dirt visible beneath the subject’s fingernails. As I stood facing the life-size portrait in the storeroom, I felt as though I’d travelled back in time to meet my grandfather in the flesh.

He is a portly, country gentleman – ‘an essentially English type’, the artist wrote. Pictured in the outdoors, his sleeves rolled up, he carries a shotgun and sports a brimmed hat with a fishing fly. He has a ruddy complexion (the feature by which he acquired his nickname) and wears an expression of fixed determination. What’s more, he bears a remarkable likeness to me and my brother. I felt I could almost speak to him – and I had plenty of questions to ask.

William Henry (known as ‘Fresh Air’) Stubbs in fishing gear outside the Black Horse Hotel in Grassington, North Yorkshire, c.1948. Photo by Bertram Unné

North Yorkshire Archives (BU04820E)

I believe Stubbs is my mother Aileen’s father. I grew up not knowing about the grandparents on her side, but, over time – through various hints and slips of the tongue – I pieced together an unfortunate family history. It was only when I reached my sixties that I learnt from my mother, who is now 96 years old, that she had once been told by her aunt, Mary, that she was the daughter of ‘Mr Stubbs’, a pub landlord.

Aileen’s mother, Lily, had been born in 1900 to a large family in Sunderland, in northeast England. In the early 1920s, she left home to go to Grassington, a beautiful village in the Dales, to take a residential post at the Black Horse Hotel as a silver- service waitress. After some time working there, Lily became pregnant and moved back home to live with her mother in the Roker area of Sunderland.

There, she confided to Mary, her sister, the identity of the child’s father and, upon the rest of the family hearing this, Lily’s brother Charlie travelled to Grassington to see him. As a child, my mother recalls seeing handwritten letters arriving at their house, which she believes contained money. It would seem that Fresh Air had admitted to being my mother’s father.

My mother had always intended to ask Lily about the identity of her father, the events that had led to my mother’s birth, and what had happened between her parents. Tragically, her questions would remain unanswered as Lily died suddenly in her bed in 1948, when my mother was just 19 years old. When I showed my mother (with much trepidation) a print of the portrait, she simply said: ‘Horrible man!’ But the truth is, we’ll never know what happened between Lily and Stubbs.

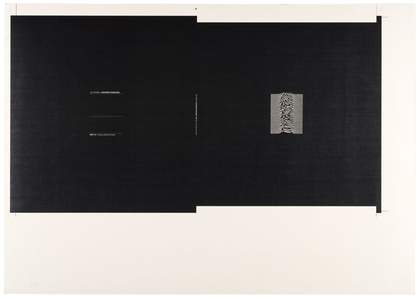

Fresh Air Stubbs standing behind his bar, c.1948. Note the reproduction of Reginald Brundrit’s portrait hanging above the door. Photo by Bertram Unné

North Yorkshire Archives (BU04820A)

Following my first sight of my grandfather at Tate Store, I came across two photographs of Stubbs held in the North Yorkshire County Council Archive, which bore a remarkable likeness to Brundrit’s portrait. If Fresh Air had been a cruel, heartless man, it doesn’t show in the pictures of him, though he does seem to have had a high opinion of himself, proudly hanging photos of himself behind his bar, and a copy of his famous portrait above the door.

I followed up my visit to Tate Store with a visit to Grassington itself. There, in the window of the village’s folk museum, was an old black and white print of the portrait, signed by the artist! When I told the local librarian that I was Fresh Air’s grandson, I began to feel like something of a local celebrity.

A friend also led me to a newspaper article that informed me that the Brundrit portrait had been shown at the Royal Academy in 1934 and 1938, and also in Paris and North America, before being presented to the Tate Gallery. The work was clearly well regarded, and I love to think of New Yorkers and Parisians looking at my grandfather. I wonder what they thought of him and the work.

I am so grateful to Reginald Brundrit for painting this portrait that he could have had no way of knowing would mean so much to a person almost 100 years later. I now keep a printed copy of Fresh Air Stubbs together with the only known photograph of Lily, supposedly also taken in Grassington – the grandparents I never knew. I would love to travel back in time and find out what really took place at the Black Horse Hotel, but these pictures are the closest I can get.

Fresh Air Stubbs was presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest in 1938.

Dave Dawson lives in Sunderland and worked as a layout artist for Apollo art magazine from 1993 to 2006. With thanks to Dave Hodgson for editorial support and Geoff Mallin for genealogy.

If you have a personal story you would like to share about an artwork in Tate’s collection, please get in touch at tate.etc@tate.org.uk.