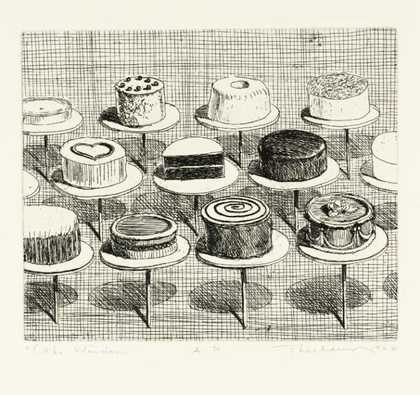

Wayne Thiebaud

Cakes 1963

© 2025 Wayne Thiebaud/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London. Photo courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

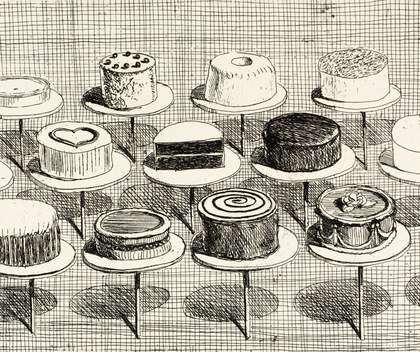

They are – with their rosettes, loveheart crowns, and cherries like appliqué beads – almost good enough to wear: rows of party cakes on raised, wide-brimmed plates, like hats on a milliner’s stand. In Wayne Thiebaud’s paintings, it’s the lustre of frosting, meringue and custard that you notice. But in his etching, Cake Window, from 1964, it is the composition as a whole that counts. This is a display in a store, tantalisingly laid out. It is the 20th-century analogue of Edgar Degas’ The Millinery Shop 1879–86. In that painting, a girl picks a peachy hat and turns it in her hands. The bonnets, with their expressive pastel frills, are almost good enough to eat.

It’s hard to think of an artist who captures better the ecstasy of choice than Thiebaud. His now famous paintings of cakes, pies and sweets – from gumballs to powder-edged volumes of marshmallow – invite you not just to take in these treats but to pore over them with the hungry scrutiny of a child. ‘Each era produces its own still life,’ as Thiebaud put it. And the still life of mid-century America was not one of domestic abundance – it was a scene in the diner and the store, behind glass. It was the potential of pleasure yet to be had.

Maybe it was inevitable that Thiebaud would be swept under the banner of pop art. He trained with commercial artists and worked as a cartoonist. For a few years, he was employed by a drugstore chain to create window advertising displays. These are the commercial arrays of cake mix boxes, recipe books and adverts – the neat, grid crosshatch of Cake Window gives it the character of a draftsman’s orthographic sketch. In his large-scale oil painting Cakes, from 1963, wedding cakes, chocolate cakes and a pristine halo of chiffon cakes are arranged in similar style to those in Betty Crocker’s Cake and Frosting Mix Cookbook, published around the same time. In the archives of Horn & Hardart – a successful automat restaurant chain in the post-war years – there are photos designed to show employees how to present the food in store. The chocolate-glazed donuts, perfectly toroid, starkly lit and arranged rank and file, could easily be a Thiebaud.

Wayne Thiebaud

Cake Window 1964

© 2025 Wayne Thiebaud/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London. Photo © Tate

And yet Thiebaud never really jibed with the sardonic cool of pop artists. His paintings are still lifes, influenced as much by Paul Gauguin as by commercial Americana. By his own admission, Thiebaud was an ‘obsessive thief ’, plundering art history for guidance. You see it most clearly in the simplicity of his shapes – elemental units arranged rhythmically across the field. These meditations on form come straight from the Paul Cézanne playbook, in which nature could be essentialised to basic forms: the cylinder, the sphere and the cone. For Thiebaud, those forms are the tempting trifecta of the pie wedge, the drum-like cake and the spherical bubblegum. ‘Nature for us men is more depth than surface,’ Cézanne wrote, and this is the world Thiebaud evokes, with his volumes of buttercream and custard, of palpable, delectable mass.

The magic is in these details, where the physicality of food and paint begins to blur. Brushstrokes bulge with the brooding, wine-red filling of a slice of cherry pie. Jam-paint drips and meringue undulates in thick impasto. Best of all is Thiebaud’s frosting. Any seasoned food stylist knows that to beautifully ice a cake, you need to handle the buttercream like oils. Smear it onto the cake with expressionistic flair. Ripple it under a palette knife. Sweep it over the cake’s elemental forms but allow it to be itself, too, holding in thick, textured strokes. This is how you make a cake truly craveable – by painting it.

Cake Window was purchased in 1990 and is available to view in the prints and drawings room at Tate Britain. Cakes is included in Wayne Thiebaud: American Still Life at the Courtauld until 18 January 2026.

Ruby Tandoh is a food and culture writer who lives in London. Her latest book, All Consuming: Why We Eat the Way We Eat Now is published by Profile Books.