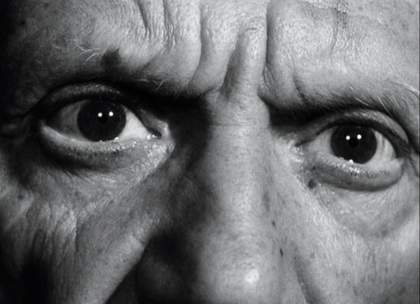

Still from The Mystery of Picasso (1956), directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot

Le Mystère Picasso, a film by Henri-Georges Clouzout: © 1956 Gaumont

'Painting is stronger than me,' Pablo Picasso scribbled on the back of a sketchbook in 1963. ‘It makes me do what it wants.’ Such a conception of genius – as a force that descends on the artist from an unknown place, making them into a conduit for creative electricity – is at once self-deprecating and extremely arrogant. On one hand, if the painter is nothing but a vessel, they cannot truly be said to be special; on the other, given that this spooky, indefinable current has chosen to flow through them in particular, it follows that they must be in some way exceptional after all.

In the 1956 documentary The Mystery of Picasso, directed by the French auteur Henri-Georges Clouzot, the mystery in question is the source of the great man’s painterly je ne sais quoi. Clouzot devised an innovative method by which he could capture Picasso’s working process, filming the reverse of his drawings as the ink bled through in real time, and recording the formation of a number of his oil paintings in stop-motion. We see Pablo himself only a handful of times: a bald head; a grey-furred paunch; a pair of dark, lively eyes in a weatherbeaten face. What is remarkable is how unremarkable he seems, and the fact that he is physically absent from most of the film, as if the paintings were appearing by magic, only further emphasises the divine uncertainty inherent in the moment of creation. We watch as a few fluid lines become an obvious Picasso – a thing of extraordinary value, in both the artistic and financial sense, generated with what seems to be a flick of the wrist. Clouzot describes the experience in language that is quasi-religious: ‘The painter stumbles like a blind man in the darkness of the white canvas’, he says rapturously in voiceover.‘ The light that slowly appears is paradoxically created by the painter.’ A paradox precisely because in this analogy, the painter is standing in for man and God. And Pablo Picasso said: let there be light.

The image of Picasso as a god of art – with all the almighty fury and potential for unfathomable cruelty that such a comparison entails – is entirely fitting in the context of his art historical reputation, in which he is positioned as a rockstar painter, a tempestuous genius, a terrible misogynist, and one of the most gifted imagemakers of the 20th century. He is the man who painted Guernica 1937, a peerless and unbearably moving invocation of the savagery of war. He is also the man who once casually held a cigarette against painter Françoise Gilot’s cheek – who informed her, bluntly, that women were ‘machines for suffering’. He made painting itself look like a power- fully masculine and sensuous pursuit, a business and a calling. In contemporary money, his net worth at the time of his death was estimated at over a billion dollars, and his astonishing accumulation of wealth became part of his appeal to the public: a rare coming together of commerce and art that suggested a savvy, intellectual brand of glamour.

Pablo Picasso

Weeping Woman 1937

© 2025 Succession Picasso/DACS, London. Photo © Tate

‘I’m the modern-day Pablo Picasso, baby’, Jay Z rapped in his 2013 single Picasso Baby; ‘I am Picasso’, Kanye West insisted the very same year, onstage in Paris; ‘Kanye West is not Picasso / I am Picasso’, the late Leonard Cohen countered in a 2015 poem called, naturally, Kanye West is Not Picasso. (In 2024, West was also the subject of a civil lawsuit that claimed he had strangled a woman on the set of a music video in 2010 while exclaiming, ‘This is f–ing art. I am like Picasso’ – an alleged act that implied that he, too, might be guilty of reducing women to suffering machines.) What all three men were identifying – and identifying with – in Picasso was this volatile, swaggering combination of affluence and acclaim, which did for the image of the artist what Hemingway did for the image of the novelist, ascribing an impressive muscularity to highfalutin, supposedly fey, creative work.

Unlike a composer or a writer, Clouzot argues in The Mystery of Picasso, ‘to know what’s going through a painter’s mind, one just needs to look at his hand.’ This seems, at first, like a curious assertion – does a composer not make annotations by hand? Does a writer not use hers to mark the page? And yet, Clouzot is right that there is something about painting as an art form that feels bodily, whether or not this feeling makes logical sense. It has to do with the idea of the brush as an extension of the self, as if it were a finger or a limb connecting the artist to the canvas, and encouraging a sequence of motions that resemble a dance – one that is gestural, abstract, and sometimes exhausting.

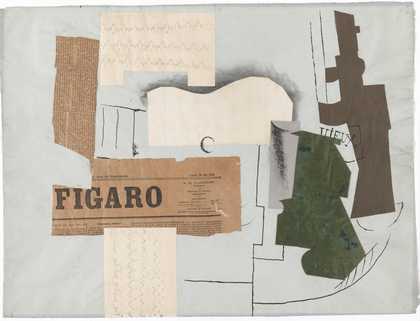

The intimate marriage between artist and work in our conception of the painter may help to explain why Picasso is as famous as a character, as he is as a practitioner, the man and his output so entwined that, in effect, he is a kind of artwork. An apocryphal tale has him scribbling a doodle on a paper napkin for a fan and then asking her for a million francs in exchange. ‘It took me a lifetime,’ he supposedly said, ‘to be able to draw this in five minutes.’ Only he could create a Picasso, whether on a napkin or on canvas, and only he could have created Picasso, the icon and the man.

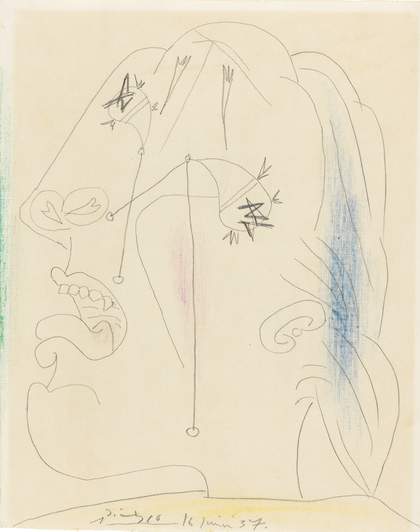

Pablo Picasso

Nude Woman with Necklace (1968)

Tate

In Clouzot’s documentary, the private performance of his painting is made public, and yet something still remains opaque and elusive in its transfer to film, as if the director had been trying to capture a miracle or a séance rather than the production of a series of artworks. No camera has yet been invented that can picture the soul of the artist, just as no reproduction of a great work of art is the equal of the thing it reproduces. Seen on a screen or in a magazine, Guernica looks like war. On the wall of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, it hurts like it, too.

That many of the pieces made for The Mystery of Picasso were destroyed after filming only adds to the project’s mythic qualities, suggesting, as it does, a startlingly offhand, cavalier attitude on the part of the artist to objects that, by rights, ought to be in a museum. Again and again, he drags some dazzling semblance of life out of nothing, and then morphs it until it is new again: drawings of men transform into women; a fish is repainted as a cockerel, and then as a face. It is a common, if reductive, complaint that contemporary cultural criticism requires our artists to be spotlessly moral, and accordingly good, or obviously villainous, and therefore bad. Whether or not this is the case, it is true that Picasso entirely resists this kind of classification, and his very resistance to it adds to the image of him as a figure who is larger than life: an artistic deity who combines Old Testament vengefulness with New Testament grace.

For Clouzot, Picasso creates something like 20 works onscreen, and crows that he could have painted more. When he does, his tone suggests a boast about his sexual prowess as much as it does an assurance of his craft: ‘I don’t mind being tired,’ he smirks like a dirty old man, ‘I can go on all night, if you want.’ On the seventh day, even God rested. Evidently, though, Pablo Picasso had more stamina.

Theatre Picasso, Tate Modern, until 12 April 2026

Philippa Snow is a critic and essayist based in Norwich. Her latest books are Snow Business (Isolarii, 2025) and It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me (Virago, 2025).

Presented in The George Economou Gallery. In partnership with White & Case. Also supported by the Huo Family Foundation. With additional support from the Theatre Picasso Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation and Tate Members.