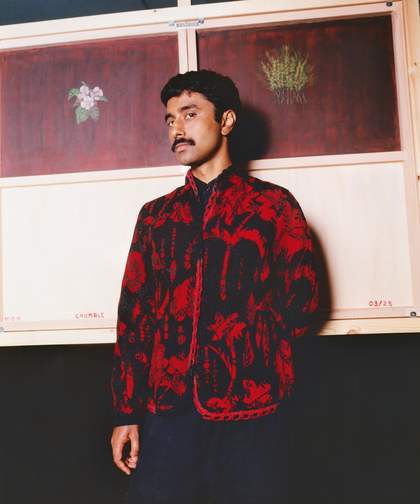

Mohammed Z Rahman in his installation Hearthside at Whitechapel Gallery, London. Photo by Tami Aftab for Tate Etc., September 2025

Photo © Tami Aftab

HANNAH MARSH You’re a self-taught painter, typically working in acrylic paint to create scenes that meditate on the migrant experience and ideas of building community. How did you get into art?

MOHAMMED Z RAHMAN My family are all creative. My mum was a seamstress, so I’m a child of the East London rag trade. We used to move between council housing often, and we always had the task of making the places we lived in feel nice. I started to paint around the same time that I learnt to cook – in my teens. Then, while I was studying anthropology at university, I made zines as an antidote to working on such a text-heavy subject. I would type them on a typewriter and paint the covers with acrylic. I used to share my work on Instagram, and in 2022 I was approached by curator Eliel Jones to feature in that year’s Brent Biennial. Off the back of that, I started working with Phillida Reid gallery.

HM I remember the small, detailed paintings at your first exhibition there, which reflected on your experience of working in a curry house. I was struck by your ability to convey a sense of vulnerability within this typically masculine space.

MZR I used to paint without any intention of showing the works. The paintings were just a way for me to process my experience – grappling with ideas of coming of age, masculinity, being part of the migrant community, and my queerness as well. At the time, I was reading a lot of race theory and gender theory as part of my anthropology degree. I tried to write about it, but it just wasn’t the right medium. It didn’t capture the emotion of the experience.

HM You recently had a show called Hearthside at Whitechapel Gallery, presented in collaboration with the Bengali culture charity Oitij-jo. It included a new series of work celebrating the act of cooking, eating and sharing food. What did it mean to you to show this work in East London, where you live?

MZR I think food offers such a fertile framework through which to look at social relationships, our relationship to the land, embodied knowledge, skill, sentimentality and memory. I felt a desire to make images about dishes that are important to me, and the life that surrounds them. In a time of heightened anti-migrant rhetoric and social division, I wanted to extend the notion of hospitality throughout the show and explore the ways in which food brings people together.

I’m very much a believer in the idea that food culture exists within people, rather than being tied to nation states. It can have a magical power to transcend and unite people across histories and territories. We are often sold the myth of ‘authentic cuisine’ – or, for example, the idea of presenting oneself as an ‘authentic’ Bangladeshi subject – but this body of work was a great way of demonstrating how one individual’s personal history can upend grand narratives of nationhood.

Mohammed Z Rahman

The Spaghetti House 2024

© Mohammed Z Rahman. Photo © Tate

HM One of the things that I find so powerful about your work is its ability to convey an emotion or narrative through the building up of tiny little details. One of your paintings in Tate’s collection, The Spaghetti House 2024, depicts a large, beautiful house made of spaghetti, with each window opening onto a different scene. It was made in collaboration with your niece, which I love. For me, it speaks to the importance of taking children seriously, allowing children to play, to be safe, and to be loved.

MZR My niece was four or five at the time, and she said to me: ‘Tell me about when you used to live in the spaghetti house.’ I went along with it, beginning a narrative that we then built up together. The spaghetti house was full of artists, and all the artists played instruments that had strings made of spaghetti. We were always confronted with challenges, like how to wash the spaghetti off our pillows every night before bed. There were all these silly, joyful stories that came out of it, but it was also a real way for me to talk about living in London house shares in my twenties. So, there’s a play of double meaning between an adult’s and a child’s perspective, which is reflected in the painting. I like to have a practice that sits between the fantastical and the real.

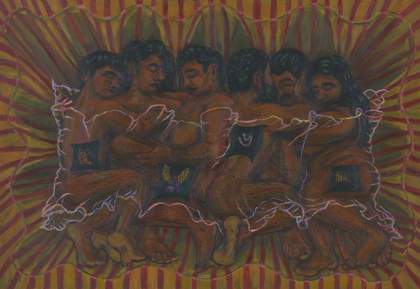

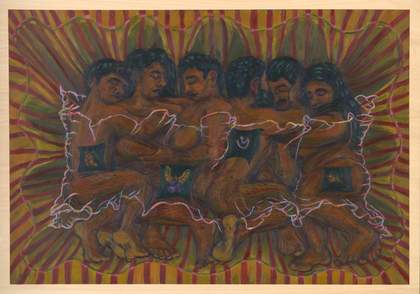

HM Another painting in Tate’s collection, The Lovers 2024, is a tender depiction of people sharing a six-way embrace. Where did the idea for this work come from?

MZR I wanted to make a representation of love. I come from quite a conservative religious background, and I was thinking about traditional ideas of spirituality and transcendence, and alternative forms of religion and spirituality that have had a recent upsurge, such as tarot and astrology. I also wanted to present an expansive notion of love, so the picture includes people of different physical presentations to be read in any combination of desire. There is an electric blanket thrown over them, which glows with the colours of the pansexual pride flag. The figures can be interpreted as laying in rest, or as upright and dancing, with their feet on solid ground. So, love is presented as restorative, but also as something active that moves things forwards – something with legs.

HM Your paintings often take us behind closed doors, revealing history and culture being enacted on a domestic scale. There is something both intimate and open about the way you share stories in paint.

MZR When you see inside people’s houses, there are always things that other people can relate to. In this way, the domestic is powerful at bringing people together, and through this familiarity, it also facilitates emotional vulnerability. It’s also important to me that you don’t need to speak English or have a certain level of education to understand my work. Knowing that people like my mum wouldn’t be able to access the ethnography I was reading at university, for example, really lit a fire in me to channel what I learn in the world in a way that is generous, sincere and inclusive.

Mohammed Z Rahman

The Lovers 2024

© Mohammed Z Rahman. Photo © Tate

HM Does this relate to the way you often include representations of alternative alphabets in your paintings, such as braille and morse code?

MZR Yes, but they’re deliberately illegible in my paintings: the morse code isn’t sounded and the braille is not embossed. Including them in this way levels people because not understanding them points to the fact that not everyone has the same frame of reference. I think this also somehow speaks to the secrecy and the privacy of personal and domestic life. There is a challenge to representing that.

HM It reminds me of my mum and gran and how they speak together at home, infusing Saint Lucian patois with their own inside jokes and some English here and there. The private world of each family’s domestic life, and the unique language that accompanies it, is a lovely notion.

MZR I’ve been really inspired by Frantz Fanon’s thinking about colonialism, as well as the work of American anthropologist Sidney Mintz, cultural theorist Stuart Hall, and ideas of creolisation. I think that’s all fed into my approach, politically and formally. And, being a Londoner, I believe in having a practice that reflects ecosystems of cultural exchange.

HM Can we talk about the importance of ecology in your work? There was a gorgeous painting of mushrooms in your show in Whitechapel. They each had their own personality, these parts of nature that might be overlooked in a traditional landscape painting.

MZR It’s grandeur on another scale. There is a lot of life around us that we’re still working towards understanding, preserving and protecting. I have been reading field guides for mushrooms and plants from an early age, and in my late teens and early twenties, I did conservation volunteering, wanting to build a connection with the land here in the city. In general, the way in which we live in the city is so convenient. You can buy almost anything in the supermarket, but with this comes a deep alienation from where food actually comes from. The mushrooms in that painting are not part of a monoculture. There are slugs and earthworms in there too, all the ecology around them.

I want to keep pushing the idea that we’re always a part of ecology, too. My family are rice farmers from rural northeast Bangladesh. They’ve got all these stories about their connection with the land, the harvest, what they would eat at certain times of year, the animals. I grew up with a sense of longing for a place I had never been.

I also want to push back against the idea that the climate crisis is a middle-class, Western preoccupation. The people who are on the forefront of the climate crisis are people in the Global South, and working-class people are most affected by issues of food security. Discussions about the climate crisis and our relationship to ecology belong to everyone.

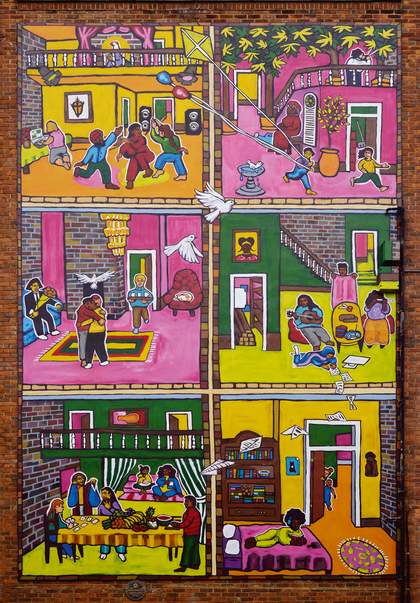

At Home 2025, the mural on the corner of Hoxton Street and Crondall Street, East London, by Mohammed Z Rahman with the Peer Ambassadors. Photos by Tami Aftab for Tate Etc., September 2025

Photo © Tami Aftab. At Home is produced by Peer, London and commissioned by Hackney Council as part of Connecting Hoxton 2025

HM Your public mural, At Home, was unveiled this summer in the East London neighbourhood of Hoxton. How did that project come about?

MZR It began with a process of deep consultation with the Peer Ambassadors, who are a group of young people from underrepresented backgrounds in Hackney participating in a creative programme set up by Peer gallery. We also spoke to market stall holders, local businesses, passers-by and people in the local park.

One inspiration was an exhibition held at Peer a couple of years ago, we are a group of people composed of who we are, which presented the work of politically conscious artists, activists and collectives working in Hackney during the 1970s and 1980s. Part of the show explored the legacy of the Greater London Council and the many progressive arts initiatives that it funded, including the London Against Racism mural campaign, before it was dissolved in 1986. I brought some of this material to the Peer Ambassadors and wanted to understand what it meant to them.

Many of them had very beautiful stories about their relationship to the neighbourhood and how they’ve built community here, and I started to build on these for the imagery in the mural, which is an imagined cross-section of a residential block on Hoxton’s Arden Estate. Across these six rooms, presented something like a comic strip, I wanted to bring out the sense of all this life happening behind these brick walls.

I also asked the young people to bring in meaningful objects from their homes to be represented in the mural and we discussed the stories behind them – for example, a wood carving with the Twi phrase Akwaaba (meaning ‘welcome’) on it, which was brought in by one of the young people who came from a Ghanaian background.

So, the mural is very affirming and uplifting, but I also wanted to give space for more challenging personal and local histories of marginality and grief. There is a room in which people are consoling each other, as well as references to the Hoxton Five, a group of young people who died in 1991. The first was killed while standing up for one of their friends who was receiving racial abuse, and the other four died in a traffic accident coming home from his funeral. There are also painted doves, which commemorate Trevor and Janice, traders who had stalls on Hoxton Market for decades before they passed away.

At Home 2025, the mural on the corner of Hoxton Street and Crondall Street, East London, by Mohammed Z Rahman with the Peer Ambassadors. Photos by Tami Aftab for Tate Etc., September 2025

Photo © Tami Aftab. At Home is produced by Peer, London and commissioned by Hackney Council as part of Connecting Hoxton 2025

HM Throughout this conversation, I’ve been struck by how many of your projects are made in close collaboration with other people. Why is this way of working important to you?

MZR I don’t think we’re individual people. I think we’re in deep community with one another. I learnt so much from the Peer Ambassadors while working on At Home, for example. You have to really listen and be receptive when trying to represent another person’s experience. As an artist, that sensitivity is a muscle that needs constant exercise.

HM What are you working on next?

MZR Right now, I’m working on another painting that centres on food. It’s going to be about chicken pie – well, it’s called ‘sikin pie’, which is how my mum pronounces it. It’s a celebration of a kind of creolised form of chicken pie that I have developed over the years, made with a shortcrust inspired by a Jamaican patty crust. It has an East Asian influence, too, which comes from my friends and the produce that is available in London. It turns the idea of the traditional British chicken pie on its head, revealing it to have a more cosmopolitan life than you might think.

HM That sounds delicious.

MZR I’m also working on a Christmas spread – but Christmas the way we have it. So, there will be jollof rice, naga wings, dumplings... Again, it will speak to ideas of refuge and coming together in the context of this very anti-migrant climate that we find ourselves in today. And then, in June, I will be opening an Art Now exhibition at Tate Britain. I can’t say too much, but it should delve further into many of the ideas we’ve been discussing in this conversation. I’m very excited about it.

HM I am too – I can’t wait.

The Spaghetti House and The Lovers were purchased with funds provided by the 2024 Frieze Tate Fund supported by Endeavor to benefit the Tate collection in 2025.

Mohammed Z Rahman is a British-Bengali artist based in London. Hannah Marsh is Assistant Curator, Contemporary Art at Tate Britain.