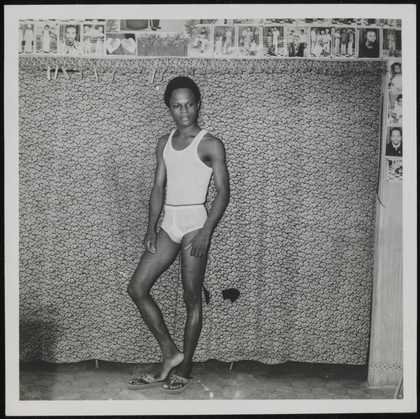

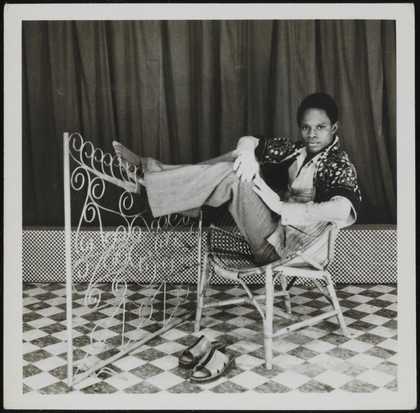

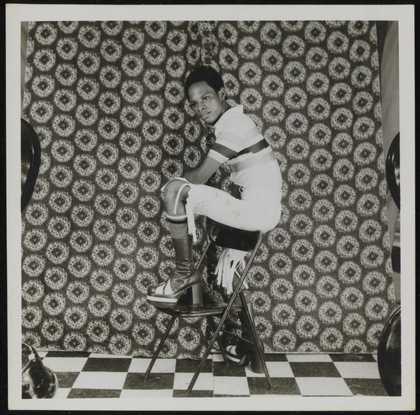

Samuel Fosso

Untitled (1978)

Tate

By the time I was born in 1958, there were already photography studios everywhere in Africa, particularly in the Central African Republic, where I grew up with my uncle after moving from Nigeria. There was even a studio next door to where we lived.

My uncle worked as a shoemaker, specialising in women’s shoes, so he taught me and I began making shoes with him. One day, when I was leaving to run some errands, I spotted the studio next door, which was also run by a young Nigerian. I went over and asked if I could learn photography, because I was finding shoemaking very hard work. He told me that I had to ask my uncle, and if he agreed, I could.

I explained to my uncle that I wanted to learn photography, but he said no,

I would have to stay by his side, making shoes. I even went to his wife to see if she could convince him. Then, one day on my way to church, my uncle said to me, ‘Listen, you asked me if you could learn photography. What are you waiting for?’ That’s when I realised that he had already spoken to the photographer next door. I started doing photography at 13 years old, and the following year, I opened my own studio.

I always dressed according to current trends. We didn’t have ready-to-wear clothing in the Central African Republic at the time, so I looked at the fashion in newspapers and magazines, the fabric and the styles, and recreated the looks. I would buy the right material, then go to a tailor, show him photos of the outfits I wanted to create, and he’d make the clothes. After I tried them on, I’d take them back to the studio and take a self-portrait to send to my grandmother.

My grandmother, who had raised me in Nigeria, was always worrying about me. So I would dress up and take a photo in order to reassure her that I was happy and in good health. Despite the photos, she was not convinced. She insisted on seeing me in person, so in 1977, my uncle agreed to take me back to Nigeria.

There, I was introduced to the music of Cameroonian-Nigerian musician Prince Nico Mbarga. I saw his record, with his photo on the cover. I knew that the shoes he wore in the picture were made in Nigeria, and I managed to buy myself a pair. I wanted to reproduce Mbarga’s look, from his clothes to the pose.

When I arrived back in Bangui, I bought a metre and a half of white denim, and showed it to the tailor so he could make demi-pantalons like the ones Mbarga wore on the record sleeve. They suited me and I struck Mbarga’s poses. I even wore the shoes to church! The priest looked at me and said: ‘You look like a real astronaut.’ Everyone wore these shoes in Nigeria, but I was the first to wear them in the Central African Republic. After that, other people started to do the same.

The clothes weren’t created specifically for art’s sake, but I really liked dressing up, and to dress up, I had to keep up with the times. I wasn’t taking the photos specifically for art, either. I never knew I was an artist, or that I was making art. So, when a French photographer helping to organise an exhibition of African photography asked me if he could see some of my photographs over a decade later, I said: ‘I [only] have my own photos. I take them for my family. They’re in my photo album, covered in dust. One day, I might get married; I was saving them so that my future children would see what their dad was like in his youth.’

He invited me to participate in the first African Photography Encounters exhibition in Bamako in Mali in 1994. I was presented with first prize, and met the great French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. He gave me the courage to continue. So, that’s how it happened: I became an artist.

Untitled was purchased with funds provided by the Acquisitions Fund for African Art supported by Guaranty Trust Bank Plc 2013 and is now on display at Tate Modern.

Samuel Fosso is an artist based in the Central African Republic. He talked to curator Valentine Umansky. Translated from French by Nolwenn Davies.