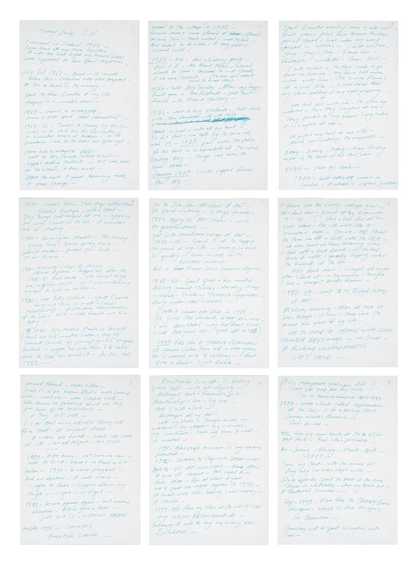

Tracey Emin My Bed 1998 © Tracey Emin. Photo credit: Courtesy The Saatchi Gallery, London / Photograph by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd

MARIA BALSHAW For the past two years we have been working on a major exhibition of your work. I thought it would be a good thing to start at the very top, with the title: A Second Life.

TRACEY EMIN So, my second life is this, now. Sometimes I think I died, and this is heaven. And my heaven is what I’m creating, this amazing art world, this world of art and art school, in a town that I knew, that I grew up in, that’s completely changed. The life that I’ve come back to is just so much better. I have done more in the last five years than I have done in the whole rest of my life.

MB I’ve been thinking a lot about some of the women artists who inspire you, and who get stronger and better as they age. You were roughly halfway through your life when you had the major health incident, and I can now see you living and making art until you’re 100.

TE A lot of women artists didn’t start their career until their sixties or late fifties. Or they might have been making art, but they didn’t have a career. I had a bit of a career before, but I didn’t have the sense of purpose that I have now. I had it within me but I never took up the baton. Now I’m carrying it and I’m much happier in that situation, taking that level of responsibility, because I think art is a responsibility, because you’re putting things into the world.

MB And because you made such an impact earlier in your career, with the quality

and the daring of the work, you had that responsibility, whether you wanted it or not.

TE Yes, but also people didn’t understand the inequality I faced back then. They didn’t, because they had nothing to compare it to. Now, people look at My Bed 1998 and say, my god, that’s 30 years ago. Or they can look at my subjects – say, abortion, rape, teenage sex, infidelity, heartbreak, whatever it is – and see just how important they are.

So, with my work, it was like climbing a mountain one step at a time, getting up there. And then finally, when I got to the top of the mountain, I stuck the flag in. And the flag is my painting. The flag is what I’m doing now. The flag is the conviction and the focus that I have now.

MB The odds were hugely stacked against you succeeding, because artists are supposed to have A levels and then go to art school, and to come from a background that can support that. But you and a number of your peers did not come from that place. Then, when you turned those qualities into your work, that too was used against you.

TE When you come from that background, it’s very different from coming from a place where it’s instilled in you to do your homework, to read books, to learn the piano, to be educated. I went to Tate first when I was 22, because I didn’t know what it was. Why would you know?

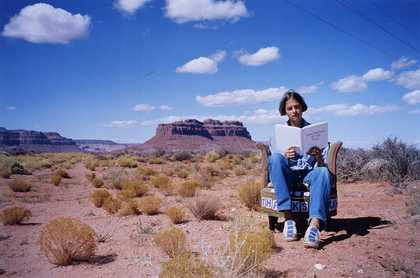

Tracey Emin

The End of Love (2024)

Tate

MB One of the things about many forms of your work is that there is an unflinching nature to it, in the things that you paint and write and examine. People naturally pull away from hurt, but you lean into it.

TE People want a quiet life, don’t they? I think when I was younger, I was the target all the time, but didn’t know how to reflect and didn’t know how to deal with it. Also, I think some of the work that I made and how I pushed myself was to an extreme, at a time when it was unappreciated. So, the more I pushed, the worse it all became for me.

Now when people see My Bed, they don’t go ‘oh’, they go ‘ah’. Because it looks so sweet. It’s so sad. It’s got this whole history, it has its own life. People actually feel for that bed. Whereas, at the time, they felt disgust and shock. It’s just a little bed really, with lots of things that show my life or how I lived for a moment.

MB I think that a lot of women who were your age or younger did understand it straight away. However, with a few brave exceptions, in the 1990s the people who recognised your work weren’t the ones who were writing the reviews or running museums.

TE There are so many reviews from the 90s, which just start off talking about my breasts, which is really shocking, because they never talk about Jeff Koons’s balls and his pink silk suit, as he swaggers in the gallery. Never, ever. So, why did they think that was all right?

MB Part of the second life, then, is that the world around you has shifted, so that we approach this show at Tate, not as Tracey the renegade, but Tracey the leading artist, the painter, and you are in the company of all of the history of painters who have pushed the boundaries.

TE Yes, and I’ve caught up with myself. So, it’s like coming back to Margate. People say, don’t you find it strange coming back to Margate? And I say, no, because Margate’s really changed, and so have I. We both have. We’re parallel.

MB What do you want the public to feel when they’ve gone through your exhibition?

TE I want them to feel. When I made my tent [Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995 1995], I didn’t want everyone to think who I’d slept with. I wanted them to think about who they’d slept with. It’s the same thing. I don’t want them to think about my life. I want them to think about their own life.

MB So, their second life.

TE If they’re lucky enough. I’m just giving them a clue how to do it.

Tracey Emin: A Second Life, Tate Modern, 27 February – 31 August 2026

A longer version of this interview appears in the exhibition book Tracey Emin: A Second Life, published by Tate Publishing in February 2026.

Presented in the Eyal Ofer Galleries. In partnership with Gucci. With additional support from the Tracey Emin Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate International Council, Tate Members and Tate Americas Foundation.