JMW Turner

The Fifth Plague of Egypt 1800

Courtesy of the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields

'He rushes through the ethereal dominions of the world of his own mind’, wrote a 17-year-old John Ruskin, elated by JMW Turner’s work. Today we are still travelling through that inexhaustible world. But if what Turner shows us on canvas and paper are inner regions of imaginative vision, they are also the outer places we all inhabit. This was no artist of self-absorbed inwardness, as Ruskin ardently affirmed. Eyes open, rather than closed in dream, Turner watched and felt the precise qualities of city squares, industrial ports, northern seas. Compelled to observe, assuming nothing – since the closely watched is always surprising – Turner had never finally seen how the sun rose over Margate, how furnaces reflected in canals, how mists diffused pale light on the River Tweed.

Turner’s places are amalgams of physical topography and mental space, aspects of reality so inseparable that they cannot be held apart. His landscape paintings are works of conceptual collage, in which the fall of an ancient empire might play out in a British valley. Wherever we are, Turner urges us to use our mind’s eye and physical sight in tandem, each strengthening the other.

The painting that prompted Ruskin’s comments is called Juliet and Her Nurse. It hung at the Royal Academy in 1836, and has not been shown in a public exhibition since; the chance to see it at Tate Britain is a highlight of the celebrations surrounding the 250th anniversary of the painter’s birth. It is a glimmering fiesta of a picture. Dusk is gathering on a night of revels in Venice. It’s just dark enough for rockets to be sent up over the water. They fizz and fade into gauzy drifts. Juliet half watches from a balcony, and we watch with her.

JMW Turner

Juliet and Her Nurse exhibited 1836

Private Collection

Shouldn’t Juliet be in Verona? Turner’s translation of her from one city to another makes a nonsense of such queries. If you look out from a window near San Marco and think of Juliet standing on her balcony, then Juliet has come to Venice. Her presence here brings the imagery of Shakespeare’s star-crossed and starlit play flickering through the evening. There is something provocative, as well as romantic, in Turner’s title. It draws attention to the roaming poetic life of this topographically particular picture. It is also unsteadying, even distracting. The ‘Shakespearean mightiness’ Ruskin felt at work here lies in what Turner does with Venice.

He had learnt the city picture by picture from Canaletto, and made his own bright ‘Canaletti’ versions of the waterfronts from low viewpoints that rendered all solid and stably balanced. Canaletto’s views of San Marco had laid out, with vivid clarity, the detail of each colonnade and market stall. Turner made his answer: from a great height, unearthed, we see the Piazza lose its geometry. Crowds move in a river, coalescing around a fire that seems to melt the buildings to rippling, luminous liquid. Most of all, the city is the night air, the iridescent dust of fireworks, the deepening colours of the sky.

War had put Europe beyond physical reach for much of Turner’s life. Regions he had wanted to explore freely were, at that time, in the enemy territory of Napoleon’s empire. During the brief peace of 1802, Turner had lost no time in getting himself across the Channel and into the Swiss mountains, where he painted the heart-stopping, vertical ravines of the St Gotthard Pass and the wide expanse of the Val d’Aosta. Then in Paris, he bedded down near the Louvre and set about studying its contents. This excursion would have to serve him in memory for decades. The pictures and landscapes that might have been a great and communal inheritance receded out of bounds.

JMW Turner

The Passage of Mount St Gothard from the centre of Teufels Broch (Devil's Bridge) 1804

Abbot Hall, Kendal (Lakeland Arts Trust)

Not that Turner regretted being in Britain – the native country enthralled him in its every murky London back alley, muddy foreshore and Tyneside lighthouse. He urged contemporary artists to embrace the potential of British climate and scenery. ‘An endless variety is on our side’, he told students at the Royal Academy. Rain squalls and racing clouds were not to be wished away while waiting for some more aesthetically acceptable kind of weather. The ever-changing northern conditions were gifts to the painter who would commit to observing their protean effects. But Turner’s mind would not be held apart from Europe or its painters. No one could keep from him the inspiration and galvanising rivalry of Titian, or the 17th-century French artists Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain. Turner’s Claudean views of English shores raised ordinary, nearby places to the status of vaunted landscape subjects, such as Tivoli and Naples. His England would blow and glimmer and work and rest in relation to many elsewheres.

Nor was Turner put off from painting European history on a major scale. Staying with friends in Yorkshire in 1810, Turner watched a storm raging through Wharfedale. Immediately, he was working up a drawing. He showed it to the teenage boy watching beside him and made a prophecy. ‘In two years’ time you will see this again and call it Hannibal Crossing the Alps.’ True to his word, in 1812 Turner exhibited a painting on an epic scale. Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps was hung low on the gallery wall, so that its blizzard was a wave about to crash over the viewer.

In his painting, the Yorkshire wind hurls rocks through the Val d’Aosta as the Carthaginian army reaches Italy. It batters the troops, whose struggles can be dimly made out in the confusion. Hannibal himself, giant figure of history, may be somewhere in the distance, but Turner was no painter of heroic portraits. His people are brought down to size among the elements that can so easily overmaster them. They are flotsam on the tide. Time, another natural force in this picture, stretches and arcs itself. This wind blasts Hannibal in 218 BCE, as it would blast Napoleon, whose propaganda feted him as a modern Hannibal. It’s also a Yorkshire wind that has become a defining feature of Wharfedale for anyone who cannot shake this picture from memory.

JMW Turner

Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps exhibited 1812

Tate. Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856. Photo © Tate

The sunlit land glimpsed beyond the blizzard in Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps is made to suggest all of Italy. It was almost another decade before Turner reached that land himself, though the ‘world of his own mind’ was already blazing with the imagined southern sun. Reprising Claude, he painted head on into the light. Repeatedly, always with new urgency, Turner recreated Claude’s ‘seaport’ compositions, in which we look out from a harbour, straight towards the sun. Such views could tell the beginning and end of empires. In Dido Building Carthage 1815, a civilisation readies itself at dawn. Boys on the harbourside push toy boats out into the water. In the pair or sequel to this monumental canvas, The Decline of the Carthaginian Empire 1817, a setting sun casts an effulgent, elegiac light on the terraces of a city and an empire nearing its end. The children and young men, now surrendered to the enemy, bid their mothers farewell. When Turner went on to paint Rome as a sunlit port, he summoned by allusion the memory of this fallen Carthage.

Ancient Italy is perhaps the most extraordinary in the whole series of Claudean port paintings that magnetised Turner over three decades. The sun emits a blaze of white, doubled by its reflection in the Tiber. It’s punishing, coruscating. We stand back from the dazzle, almost raising a hand to shield the eyes, but we must draw closer to makes sense of the shapes. The buildings look unsteady, deliquescing. Objects are strewn in a dark tangle across the foreground. A group of figures, seen indistinctly, hold a man by force. The second part of the title gives the subject: Ovid Banished from Rome.

Since youth, Turner had known Ovid’s poetry; those wild, shape-shifting stories were dominions he rushed through and metamorphosed in paint. But here is the arrest of the poet; here is the stoppage and casting out of creative power. Turner showed Ovid’s tomb, already built. He knew the melancholy works in which Ovid mourned his exile on the Black Sea as a kind of death. Turner paints the end of Rome’s great writer as the demise of Rome itself. That white sun is warming no one, and in another moment the Tiber will be in darkness. Harnessing the visual language he revised and honed through all his port pictures, Turner makes a political protest that reaches back to antiquity and forward to us in the present. The arrest of a poet signals that a whole civilisation is in decline. The suppression of imaginative freedom is no marginal matter but casts glorious empires into cooler light.

JMW Turner

Ancient Italy: Ovid Banished from Rome exhibited 1838

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence

Ancient Italy was exhibited in 1838, two years after the painting of Juliet in Venice. Both are vehement affirmations of imaginative freedom. These works of Turner’s sixties are mysterious, indefinable, liable to change as we look. The ‘many-coloured mists’ above Turner’s Venice appeared to Ruskin as souls or spirits released from Italian earth into the bright heaven: ‘Instinct with the beauty of uncertain light they move and mingle among the pale stars’. That phantasmagorical quality is there too in the meditation on Ovid’s banishment. The scattered scenes in the foreground appear as spectral figments. Perhaps all Turner’s insubstantial figures are ghosts of a kind. Even the buildings of his cities seem to ‘move and mingle’ as if they were briefly visible emanations of mist, sun, or storm.

Detractors complained in the 1830s that the artist had turned away from nature: that he was muddling the reality of things, resorting to fantasy. But no one was looking harder. If the spirit of place took mysterious forms in his art, it was through intensity of study rather than lack of it. At the height of his fame, when he might have rested a little, when he could justifiably have claimed to know enough about sunsets, Turner still considered each day’s new reality unmissable.

Returning to Venice in 1840, he tirelessly filled more sketchbooks. The young English artist William Callow was staying at the same hotel and saw something he would always remember. ‘One evening whilst I was enjoying a cigar in a gondola I saw Turner in another one’. Callow was sitting back, absorbing the atmosphere. He peered across the water. Turner, he realised, was not basking but creating. There he was, ‘sketching San Giorgio, brilliantly lit up by the setting sun’. ‘I felt quite ashamed of myself idling away my time whilst he was hard at work so late.’ That was the work, those were the late hours, this was the continuous effort by which Turner made sure to see whatever the sun might show him, and to search his own ‘ethereal dominions’ by its daily light.

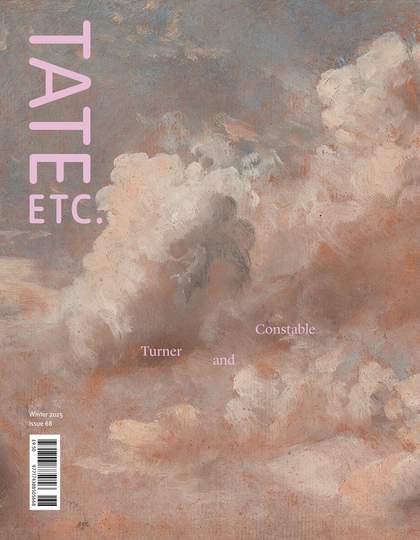

Read on: Under The Same Sky: John Constable

Turner and Constable, Tate Britain, until 12 April 2026

Alexandra Harris is Professor of English at the University of Birmingham. She is the author of several books, including Weatherland: Writers and Artists Under English Skies (Thames & Hudson, 2015) and, most recently, The Rising Down: Lives in a Landscape (Faber & Faber, 2024).

Turner and Constable is in partnership with LVMH. Supported by the Huo Family Foundation and James Bartos. With additional support from the Turner and Constable Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation and Tate Members. The media partner is The Times and The Sunday Times. Research supported by the Manton Historic British Art Scholarship Fund.