It was seven or eight years ago that Tacita Dean told me that Marcel Duchamp had spent a few summer weeks of 1913 in Herne Bay, a small seaside town on the north Kent coast. The very incongruity of the story was its own fascination, seemingly its own confirmation also, although perhaps one should be wary of the storyteller’s ways. No-one I spoke to had heard of the visit – and in such an important year for the artist too – but a brief consultation of Calvin Tomkins’s biography appeared to substantiate Tacita’s story. From other sources, also, information was gathered: the artist arrived in the coastal town in early August to act as a chaperone to his younger sister, Yvonne, who was taking a course in English at Lynton College. On 8 August 1913 he wrote to his friend Raymond Dumouchel: “The traveller is enchanted. Superb weather. As much tennis as possible. A few Frenchmen for me to avoid learning English, a sister who is enjoying herself a lot.”The postcard on which this is written shows the pier, at that time the second longest in the country, and the recently constructed Grand Pier Pavilion, a building that left an impression upon the artist. I had become marked also. A move to a town a few miles from Herne Bay and a Nesta Fellowship provided the impetus, and the means, to explore Duchamp’s visit further, and I decided to make a short film based upon it, a fiction founded upon certain facts.

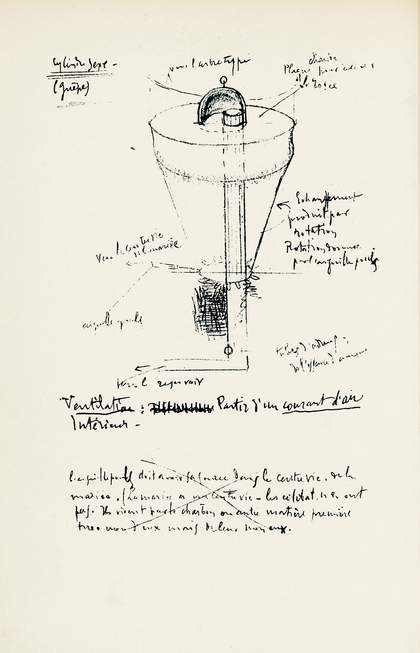

Following his succès-de-scandale at The Armory Show in New York with Nude Descending a Staircase 1912, Duchamp’s work was already notorious, but his arrival in England attracted no attention. Although out-of-sorts shortly before coming to the UK, once in Herne Bay, he continued to make notes for the major work on which he was engaged, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even 1915–23, or as it has come to be known, The Large Glass. He made four drawings in Herne Bay, two of which, Pendu Femelle and Wasp, or Sex Cylinder, were deemed important enough to be included in Green Box 1934. Duchamp also clipped a photograph from a leaflet showing the Grand Pier Pavilion illuminated at night, which was later attached to one of his most important notes, in which he describes a possible background for The Large Glass: “An electric fête recalling the decorative lighting of / Magic city or Luna Park, or the Pier Pavilion at Herne Bay.”The note goes on later: “The picture will be executed on two large sheets of glass about 1m 30 x 1,40 / one above the other (demountable).” Although none of these notes is dated, one must assume that this was written after, or during, Duchamp’s stay in Herne Bay; it also appears to be the first time that his major work is described as a work on glass.

Facsimile of one of four drawings by Duchamp done in Herne Bay, called Wasp, or Sex Cylinder 1913

© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2006

As my film is about the possible discovery made by a fictional character researching Duchamp in Herne Bay, I began to speculate what this might be. Perhaps the rare colony of digger wasps found a mile or so along the coast, and especially active during August, might provide a more plausible explanation for the appearance of the word wasp in the title of two of Duchamp’s drawings than the African myths put forward by Arturo Schwarz? And what of the glass of The Large Glass itself? Might my fictional French character have been struck, like the young artist before him, by the large sash windows of the grand Victorian houses in the town, features that are commonplace in British housing, but rather unusual on the continent? It is entirely possible that this would have been the first time that either man would have seen them in such abundance, if they had seen them at all. Perhaps my character would have been reminded that Duchamp later intended to make a whole series of works based upon windows, although only two small pieces were completed, including the punningly titled Fresh Widow 1920? He would have known that the French for widow is veuve, a colloquialism for the guillotine; he may have known, or could have easily discovered, that fenêtre à guillotine is the French term for sash window. As the two elements of the window are demountable, like the two sheets in Duchamp’s original note, might he have speculated that The Large Glass be reconsidered as a sash window? If this were the case, then perhaps the Bride and her Bachelors may be reconciled after all, the one sliding, gliding, on top of the other.

Speaking to Schwarz some time later, the artist remarked: “Instead of being a painter, I would have liked, on this occasion, to be thought of as a fenêtrier.” Perhaps already, in Herne Bay in 1913, Duchamp was both bachelor and windower?