Leonora Carrington is one of the most original and visionary British artists and writers of the twentieth century. She is also – and this is surprising when you consider the vividness and breadth of her work – one of the most underrated. Now living and working in Mexico (shortly she’ll be 89 years old), she has never quite slipped the label of Surrealist, and is still, perversely, best known as the ex-debutante wild-child Surrealist muse, the companion of Max Ernst in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

But Carrington has been working her own unique and startling aesthetic furrow all her life. She wittily signalled what she saw as Surrealism’s datedness, tameness and acceptability as early as 1950 when she finished her far-sighted novel, The Hearing Trumpet. ‘Even Buckingham Palace,’ she writes in it, ‘has a large reproduction of Magritte’s famous slice of ham with an eye peering out. It hangs, I believe, in the throne room.’

Her paintings, dark and colourful, are characterised by a playfulness, a revelation of spirited belligerence and a profound, magical and yet quite dinner-table-practical otherworldly vision. They tend to be full of chatting social animals, strange creature-like humans, many-armed lizard-snakes, people turning into creatures (or creatures turning into people), standing, waiting somewhere evocatively theatrical between benign and malign. They reveal the animal nature of humans, the social nature of animality and the enchanted, ritualised space where these natures meet and become hybrid.

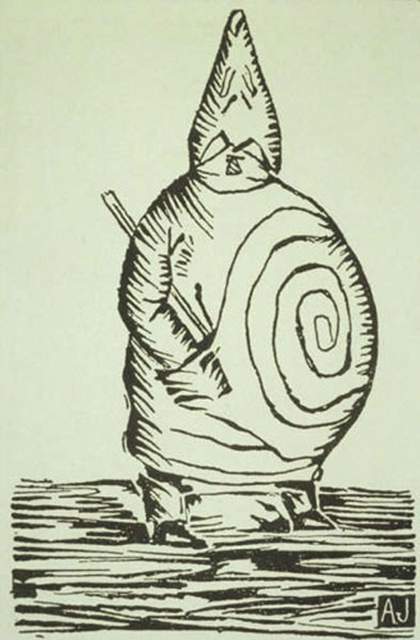

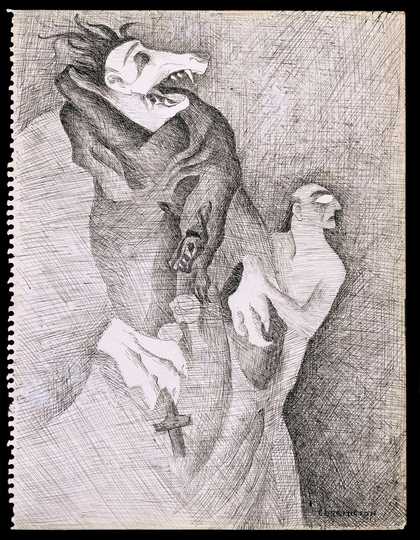

This makes all the more interesting the two previously little-known ink on paper works purchased in 2004 by Tate and now hanging in Tate Modern. Do You Know My Aunt Eliza? and I Am An Amateur of Velocipedes both 1941 share an as-yet unritualised, or unframed, directness of image, providing almost at a glance a clear access to some of the central concerns of her art.

The pictures are not a pair, though in their pairing they provide an extraordinary insight into her use of light and darkness, even at her sparest and with the sparest of materials. They are comic and witty; like all her work intent on questioning sexual and religious apparition and existence. Both ask questions about imprisonment and liberation. (If it helps at all to be autobiographical, 1941 is the year following Ernst’s repeated incarceration, first by the French authorities as ‘alien’, then by the Nazis as ‘degenerate artist’, after which the young, intelligent and rebellious Carrington endured her own incarceration in Spain, in an asylum, having suffered a breakdown.)

Both bear interesting comparison with one of her late 1930s short stories, As They Rode Along the Edge, in which a parsimonious saint tries to fool a bunch of savvy creatures and their leader, a hirsute wild girl called Virginia Fur, into letting the church have, at its leisure, not just their souls but their bodies too. Virginia spends her time, followed by a horde of cats, whizzing round her territory mounted on a wheel. ‘Riding a wheel, she took the worst roads between precipices, across trees. Someone who’s never travelled on a wheel before would think it difficult, but she was used to it.’

Each picture draws attention to the eye. Each refers to blindness and seeing – in the demon figure in Do You Know My Aunt Eliza? and the angel figure in I Am An Amateur of Velocipedes. Are you led or are you driven? These pictures are led – and driven – by a duality which emerges from and coheres into a single form. Both reveal a fascination for religion, with a Gothic, almost operatic revelation of religious savagery in one, and a revelation of benign sexual ecstasy in the other – something that allows the woman on the wheel to appear so far beyond ‘amateur’ and cyclist as to be the figurehead of her own ship.

Leonora Carrington

Do You Know My Aunt Eliza? (1941)

Tate

In her yoked, seemingly constrained position, Carrington floods her with power. Her angel-driver (is he the agent of flight and movement or is it the woman?) is garlanded by a long-necked bird. Where Do You Know My Aunt Eliza?’s motifs are all teeth and claws, a fusion of social frippery and fury, and those of I Am An Amateur’s are erotic in the suggestion of unexpected feathers and repeated spirals. Both configurations are dynamic in subject and realisation – and in both pictures, the figures are moving somewhere beyond the observer’s gaze, suggesting a whole narrative and world beyond their own frame and beyond our seeing.

Their comic titles are typical of Carrington’s lightness, something that imbues her often arcane imagery with unexpected humour. Her playfulness can make explicit, for instance, the foul social power of the savagery in Do You Know My Aunt Eliza? and also the shining sexual freedom fused with happy naivety in the new knowledge of sexual positioning in I Am An Amateur of Velocipedes. That’s what her fusions of creature and human, of natural and social, of liberation and oppression, of practical and arcane, reveal – the workings of power, for good or bad. The act of revelation itself is, crucially, non-judgmental. As she wrote in her long story, The Stone Door:

However deeply we look into each other’s eyes a transparent wall divides us from explosion where the looks cross outside our bodies. If by some sage power I could capture that explosion, that mysterious area outside where the wolf and I are one, perhaps then the first door would open and reveal the chamber beyond.