Pierre Huyghe

A Journey that wasn’t 2005

Animatronics, fur

© Photo: Xavier Veilhan/courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris and the Public Art Fund

All images are born equal today, from family snapshots to works of art, via Hollywood movies. The important thing is that they can be compared – that they can be judged. We can always claim the opposite and think in terms of the medium, or develop a rhetoric of resistance, but that would mean contemporary art finally being reduced to the narrow dimensions of its distribution circuit and institutional apparatus. Let’s say that the forms produced by artists at the beginning of our twenty-first century constitute a kind of wildlife reserve: they evolve a little more freely than the others, even if they are subject to the same economic and idealogical constraints as them. Pierre Huyghe’s strength lies in his understanding of the fact that an image always comes with baggage. This is probably what makes his work so important today, at a time when commercial signals are proliferating in place of works, closed-loop communication is coming to replace culture, images have become masks for universal media ventriloquism and it’s always power that does the talking.

1. Platforms

Chantier permanent (A permanent construction site), the title of one of Huyghe’s works, could apply to them all. The image of the construction site actually contains the essential part of what we find in his universe: the fleeting, fragile nature of human labour, the relationships of which it is composed, a complex picture of the flows, connections and tools that it requires and, more generally, an ethical conception of form, never considered as a finished product, but rather as the fruit of a slow elaboration. In his work, duration, interrelations and forms constitute a hub, a knot that it would be vain to try to sever. If, as Gilles Deleuze has written, “a philosopher’s style is his movement”, then Huyghe’s should be sought not in any stylistic recurrence, unlike so many fashionable painters for whom the essential thing seems (once again) to be recognised at first glance, but rather in the methods and devices that he uses. From his series of billboard projects including Chantier Barbès-Rochechouart 1994, in which he positioned above a construction site a photographic billboard of the work being carried out there, to A Journey that wasn’t 2005, a sumptuous musical comedy commemorating his expedition to the Antarctic, Huyghe has asserted the work of art as a zone of activity, a form filled with human interactions and economic, political and social phenomena.

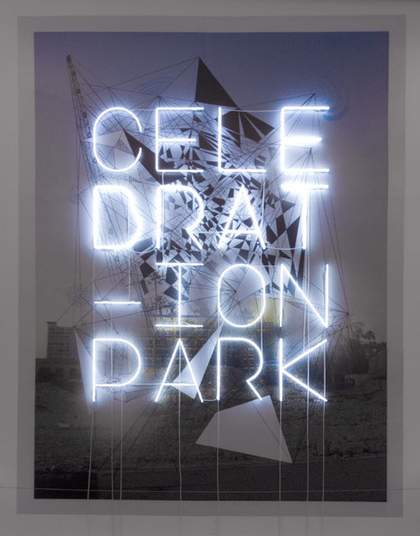

Pierre Huyghe

A Journey that wasn’t 2005

Film still

© Photograph: Pierre Huyghe

Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris

Manet painted the individual in the urban crowd. Warhol depicted the individual caught in the media snare. The typical individual described in Pierre Huyghe’s art is the one who seeks to master his living conditions – in short, the very opposite of the alienated worker. The Marxist idea of alienation has become more complex over time, because the framework of the professional world has constantly expanded: spare time, dependent on working hours, forms an integral part of this, as do all the representations that structure daily life. Freedom is a vast theme, so much so that it seems too big for most of today’s artists. How do we rethink freedom; how can we produce a work on the basis of this subject? If Huyghe is an important artist, it’s because he isn’t afraid of re-problematising apparently classic themes, while taking the world of work as his starting point. Here is an example. John Wojtowicz, responsible for an act of hostage-taking in Brooklyn in 1972, saw his story adapted for the cinema by the director Sidney Lumet, with his role interpreted by Al Pacino in the film Dog Day Afternoon. Is he just a subject from a news item, a vague “model”, or is he, by contemporary standards, the author of a screenplay? The video The Third Memory, for which Huyghe asked Wojtowicz to replay an episode from his own life, thus calling on him to reappropriate it, poses the question of the relationship between fiction and reality: does one work for the other? When one constructs a story with one’s own body, isn’t that a piece of writing, a work that deserves to be protected by copyright as much as any other? Lucie Dolène, the French performer of the Snow White song in the eponymous cartoon, is subjected to a similar procedure in 1995’s Blanche-Neige Lucie (Lucie Snow-White), the film that enables her to reappropriate her voice, “stolen” by Walt Disney. In the project No Ghost Just a Shell 1999–2002, done with Philippe Parreno, similar territory is covered. Having bought the copyright of Ann Lee, a Japanese manga character awaiting activation, the two artists decided to examine the rights and conditions of productivity of a sign, as though she were a human being in the labour market. Ann Lee, condemned to a short life by the entertainment industry because of her status as a cheap character without any particular qualities, thus found herself “saved” by a project that handed her features over to a ten-member co-operative of artists ranging from Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster to Joe Scanlan.

The idea that the separation between life and work and their representation is only an artificial construct undertaken for political reasons is a central notion in Huyghe’s oeuvre, as exemplified in the foundation in 1995 of l’Association des Temps Libérés (Freed-Time Association), which includes artists Maurizio Cattelan, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Carsten Höller, Liam Gillick, Philippe Parreno and Rirkrit Tiravanija. As Huyghe says: “The ambition of this project was to provide a social structure for a group of individuals at a given moment, and, in a way, to extend the duration of that given moment.”

Huyghe notably perpetuates this through the omnipresence of the platform, whether it be a stage set or one on a construction site. Both are meeting places for skill and creation, economy and private life, at once the product itself and the making of it. A cinema or television set is a place of collective elaboration, a space of interactions between different people, each bringing with them their history, their competence, their labour. In short, an ideal miniature of the working community. Multiscénarios pour un sitcom (Multiscenarios for a sitcom) from 1996 called for the construction of a working community, produced on the basis of pre-existing scenarios.

In the society of the spectacle, everyone can lay claim to performer status. Huyghe’s work takes account of the fact that human activities are no longer inscribed solely on specialised surfaces, but everywhere – because the human city has become a vast recording process, from surveillance cameras to the mass media. As the philosopher Jean-François Lyotard has written, swimming is an inscription, just like painting.

On the other hand, are we not constantly confronted in galleries today with works that stupidly stammer out their version of “identity” or “human nature”? According to Marx, the only element that allows us to define this much-vaunted human nature is nothing other than the system of relations introduced by human beings themselves: the human is the inter-human, the dealings between all individuals, which is to say that society is not based on any kind of nature, but is the product of a huge and constant negotiation, a perpetual montage.

Pierre Huyghe

Still from One Million Kingdoms 2001

Video installation with sound, 7 min

Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York and Paris © Pierre Huyghe

In our own times, a work of art with a political ambition can ignore neither the reality of the inter-human sphere nor its status as a montage of scenarios, at the risk of being considered other-worldly – because otherworldliness today lies in an excess of abstraction and idealism. From this point of view, attempts by conservative critics to pin a label of simplistic Marxism on Huyghe’s art are just a way of confining political discourse within a radicalism restricted to the university campus and academic debate. If the contemporary work produces political effects, as is demonstrated to dazzling effect by Pierre Huyghe, it is because it takes as its starting point concrete inter-human realities, rather than an abstract idea of alienation.

2. More light.

Using the tools of production made available to an audience – events, processes, objects or images – Huyghe suggests structures that enable us to interpret life, rather than simply being subjected to its formatting processes. His art seeks to create a kind of alternative editing suite for social scenarios. It allows us to re-compose the screenplays that define our daily life, to replay “social times” on a different scale. Thus, his works function like temporal scores, orchestrating lived moments - just as the musical comedy of A Journey that wasn’t forms an equivalent to the journey, and The Third Memory enables Wojtowicz to bring closure to his story after a detour through Hollywood fiction.

Mehr licht! – Goethe’s last words: More light. Light in Huyghe’s art is, above all, cinematic: it’s bigger than life, intense, constructed to be seen from a distance, because it is often surrounded by total darkness. It can reproduce natural movement, as in 2002’s L’Expédition scintillante (The sparkling expedition) at the Kunsthaus Bregenz, or it can turn into a firework ( No Ghost Just a Shell).

In A Journey that wasn’t, this meant inverted light and shade – a reconstruction of the Antarctic landscape in New York’s Central Park, but with black glaciers bathing in a black sea, beneath a flood of intense light, where the audience became the performers. Passing from the positive (of the journey) to the negative (of its transcription) means that every utterance is a translation; every act of showing commemorates the event to which the artist refers. Or as Huyghe puts it: “I am fascinated by this idea of reality being so unbelievable that to tell it the right way, you must tell it as a fiction.”These statements, once again, derive from an ethics of form. Of course we might read in them a contemporary equivalent of Duchamp’s theories of the readymade (“inventing a new idea for the object”), but for Huyghe the crucial thing is to draw on the lessons that art can learn from the industry of the contemporary image, opposing a categorical veto upon any post-documentary manipulation, and to impose the maximum number of precautions upon the production of forms.

A researcher, traveller, narrator and organiser of events, Huyghe translates forms from one state to another – a piece of architecture is transformed into music and a store of information into a community ( Streamside Day), a journey into a musical comedy ( A Journey that wasn’t), a fiction into a documentary ( The Third Memory), a casting session into a television channel (the set in Multiscenarios for a sitcom/MobileTV ), or an investigation of an institution into an opera for marionettes ( This is not a time for dreaming).

This insistent multifariousness is a corollary of his refusal of that contemporary media practice of taking the place of the other in order to speak in his name – a kind of ventriloquism. That refusal is a part of Huyghe’s ethic of translation: one must not speak for the other, but speak with him, one must include the other and the elsewhere in the frame. The last word should go to the Italian novelist and playwright Luigi Pirandello: “The reversibility of appearance and reality is the only means of artistic access to the real.”