Undated photograph of Voroshilov, Molotov and Stalin, with Nikolai Yezhov, commissar of water transport, deleted. He was shot in 1940

© Courtesy the David King Collection

The cheap propelling pencil with which I’m writing this essay has a tiny white eraser tucked beneath its shiny top. I hardly ever use it – the action required is just too fiddly, and the metal cap likely to get misplaced between my second thoughts and the last stroke of rubber on paper. And anyway: what happens if the eraser runs out before the lead? A nagging thought like that could wipe the next sentence from my mind before I’ve erased the last. Actually, rubbing out what I’ve written – and writing this, as always, will be largely a matter of erasure – is only the most drastic option. A quick scribble will do to rid the page of a botched clause or an unhappy adverb. Alternatively, I might score the offending formulation through with a single line, so that it can be reinstated later, if things get desperate. In a hurry, I’ll simply overwrite the old text, reshaping its letters where I can, obliterating others, as though shouting myself down. The result is a scattered mass of grey text, pretty much unreadable to anybody else.

Erasure is never merely a matter of making things disappear: there is always some detritus strewn about in the aftermath, some bruising to the surface from which word or image has been removed, some reminder of the violence done to make the world look new again. Whether rubbed away, crossed out or reinscribed, the rejected entity has a habit of returning, ghostlike: if only in the marks that usurp its place and attest to its passing. But writing, for example, is already, long before lead hits pulp, a question of erasure, an art of leaving out. Every painting, said Picasso, is a sum of destructions: the artist builds and demolishes in the same instant. Which is perhaps what Jasper Johns had in mind when he said of Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing 1953 that it embodied an ‘additive subtraction’: after a month’s sporadic destruction, and 40 spent erasers, what is left is a surface startlingly alive, active, palimpsestic.

What the eye picks out as meaningful on a printed or marked surface is mostly down to learning and convention: the legible text or image floats free of the surrounding remnants of abandoned language, meaningless doodles or flaws in the texture of the flat support. The real message hangs in the air like a street full of neon. Still, there is something seductive about the idea of an erased truth lurking between the lines.

The classical or medieval palimpsest is the ur-image of what happens when you try to wipe the slate clean. The parchment, vellum or papyrus scroll, its original writing scraped away, was regularly redeployed in an era when scarcity of materials won out over considerations of posterity. The ancient palimpsests were deciphered, by chemical means, in the nineteenth century, and immediately supplied a ready symbol for the workings of the as yet half-built machinery of the unconscious. In 1845 Thomas De Quincey, who had earlier written that ‘there is no such thing as forgetting possible to the mind’, described the submersion of experience in memory precisely as a text erased and overwritten. Like its written counterpart, the ‘palimpsest of the human brain’ will one day reveal its secrets to the chemical wash of involuntary memory. Erasure, it turns out, is just a particularly profound form of preservation.

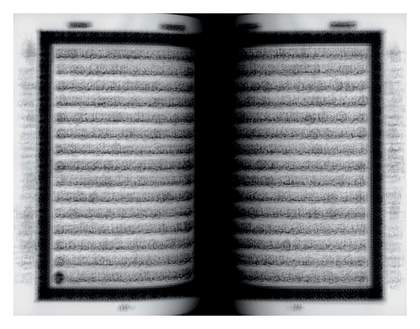

Visually, the contemporary art that most resembles the palimpsests of antiquity is the photography of Idris Khan. Strictly speaking, nothing is erased in Khan’s work, but rather overlaid to the point of illegibility. It amounts to the same thing: in every… page of the Holy Koran 2004, the sacred text overwrites itself until it is a blur of meaningless ciphers, and the vertical gutter between the pages a deep black void. The scores of Chopin and Beethoven are subjected to the same superimposition, their notes clotted like flies.

Idris Khan

every... page of the Holy Qu'ran 2004

Lambda digital C-print mounted on aluminium

136 x 170 cm

© Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery © Idris Khan

If Picasso was right, and every painting nullifies other possible paintings, we can none the less acknowledge degrees of undoing. There are single brushstrokes, hastily scraped away, of which we will never know a thing. But are we still speaking of erasure in the case of entire extant images later overworked? What of those works that have been discovered to consist of a tissue of adhesive layers – the x-ray spectre, for example, of a kneeling figure found beneath Leonardo da Vinci’s The Virgin of the Rocks 1483–6? Such cases of images overpainted into oblivion remind us that a painting is both thick and thin at the same time – its physical extension supports its surface flatness, which in turn suggests a notional depth. A painting – at least a figurative painting – which is, as it were, too deep, risks becoming a glutinous mess, erasing itself by its very urge to completion. In Honoré de Balzac’s story The Unknown Masterpiece 1837, the great painter Frenhofer labours for years at a picture of a young woman, until she disappears, leaving only a tiny, perfect foot looming out of the surrounding chaos: ‘Colours daubed one on top of the other and contained by a mass of strange lines forming a wall of paint.’ By unintentionally erasing his painting, Frenhofer has in effect produced the first Modernist monochrome, but he has done it by larding his canvas with too much significance, not too little: excess is a form of erasure too.

Leonardo da Vinci

The Virgin of the Rocks

Tracing of underdrawing superimposed on the original painting

© The National Gallery London

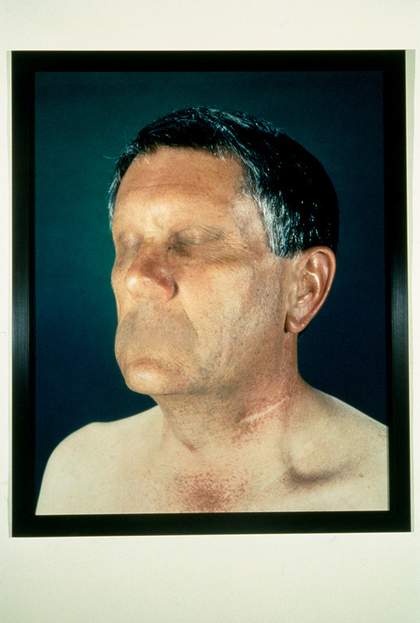

More than any other image, an erased human face remains horribly eloquent. In fact, a face cannot be made to vanish completely: it stays sufficiently human to horrify by its exact lack of humanity. Hence the unnerving effect of Georges Franju’s film Eyes Without a Face 1959, in which a young woman, disfigured in a car crash, is subjected to her father’s insane and murderous plan to give her a new face. We never see the daughter’s ravaged face, but the featureless white mask she wears for most of the film is enough to suggest her uncanny oscillation between human and inhuman. Something of that enigma is captured too in the digitally manipulated photographic portraits of Anthony Aziz and Sammy Cucher, from whose Dystopia series 1994–5 the features have been removed, leaving a smooth, affectless but somehow tragic surface.

Aziz + Cucher

George from Dystopia series 1995

C-print

127 x 102 cm

© Courtesy Henry Urbach Architecture © Aziz + Cucher

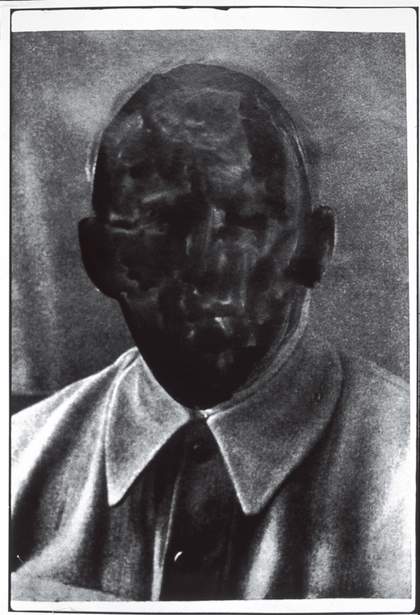

In his book Defaced: The Visual Culture of Violence in the Late Middle Ages 2004, the Swiss historian Valentin Groebner links this double valence of the disfigured face to the term ungestalt: a word used to describe the literally formless features of those lying dead on battlefields: ‘Violence was shown in and with pictures, but the pictures showed only a terrifying void.’ Similarly, in the collection of doctored or defaced Soviet-era photographs amassed by David King for the book The Commissar Vanishes and the exhibition of the same name, the most affecting images are not those in which individuals have been entirely removed by the retoucher’s art, but the photographs from which, in private, the faces of the victims of Stalin’s regime have simply been rubbed out.

Alexander Rodchenko’s book Ten Years of Uzbekistan was published in 1934. During the Great Purges it became illegal and Rodchenko was compelled to deface it. Akmal Ikramov (left), first secretary of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan, and Yan Rudzutak (right), former Party member from Latvia, were shot in 1938

© Courtesy the David King Collection

If the erased face always conjures the image of some primal violence, the expunged word inevitably attests to a repression of some kind, whether psychological or political. In the coy ellipses with which, in the novels of the eighteenth century, readers were invited to imagine undescribed erotic adventures, on the blacked-out pages of classified documents, or in the cancelled lines of a prisoner’s censored letter, the lost word denotes the intercession of authority.

In an essay entitled A Note Upon the Mystic Writing Pad 1925, Sigmund Freud proposed a deceptively simple image of the relation of the conscious and unconscious mind. The object in question is a child’s toy, a resin or wax tablet over which is laid a thin transparent sheet:

One writes upon the celluloid portion of the covering sheet which rests upon the wax slab. For this purpose no pencil or chalk is necessary, since the writing does not depend on material being deposited upon the receptive surface. If one wishes to destroy what has been written, all that is necessary is to raise the double covering-sheet from the wax slab by a light pull, starting from the free lower end.

Conscious thought or feeling, in other words, is made to vanish into the unconscious. But as anyone who has played with such a toy as a child will recall, the words survive as faint impressions; hold your Etch A Sketch at the right angle to the light, and all your previous inscriptions are still visible.

A work by Joseph Kosuth, entitled Zero & Not 1986, points out both the psychoanalytic attitude to language and the tendency of Freud’s words to assert their authority despite our efforts to wipe them out. A Freudian text is printed on the gallery wall, then struck through with black tape, so that it is erased but still insists. It remains more or less readable: its lesson – the lesson of psychoanalysis; a lesson, after all, about the impossibility of erasure – simply won’t go away.

The fondest, least plausible dream of Modernist art and literature was of a world without memory: a cultural tabula rasa from which all trace of the styles of the past had been erased. The arts of evacuation imagined by the likes of Samuel Beckett, Yves Klein and John Cage aspired to a deliberate vacuity: a vacant stage, an empty gallery, a silent orchestra. But in each case the project is impossible: some sound, image or word will intervene to recall the world left behind. The point is made, belatedly and in the most banal way, in Michel Gondry’s film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind 2004, which takes French artist Pierre Bismuth’s elegant and witty idea – writing to friends to inform them that they had been erased from his memory – and turns it into a predictable tale of love’s mnemonic power: there will be no real forgetting of the crossed-out lover, and erasure, after all, will be just like starting over.

‘What we require is silence, but what silence requires is that I go on talking,’ declared Cage in his ‘Lecture on Nothing’: the silence dreamed of by the art of the last century is always expectant, about to be spoken into. In 1996 the artist, writer and curator Jeremy Millar interviewed the novelist J.G. Ballard, began to duplicate the tape before he transcribed it, and accidentally erased hours of the great man’s thoughts. The ruined cassette, one long pregnant pause, could only become an artwork: Erased Ballard Interview 1996–2001. You listen, heart in mouth, just as Millar must have done, hoping that Ballard’s cultivated tones will, any second now, interrupt the hiss. And at the same time you hear everything in this piece: the whole history of the avant-garde affair with emptiness, the dematerialisation of the work of art, its evanescence into pure idea or gesture, up to and including Rauschenberg’s erasure of de Kooning’s drawing – all of it, suggests Millar’s blank tape, is merely an absurd error.

Maybe the total erasure of a work of art, or the making of a work that had an utter absence at its heart, was never possible to begin with, or maybe it’s simply a fantasy to which contemporary art is no longer willing to give itself over, except playfully. Ignasi Aballí’s Big Mistake 1998–2005, in which the artist painted a Modernist black square on the gallery wall, then overpainted it with Tipp-Ex, or Correction 2001, which does the same thing to a mirror, are reminders that something is always left behind, like the Cheshire Cat’s grin in Through the Looking Glass:

‘ “I wish you wouldn’t keep appearing and vanishing so suddenly: you make me quite giddy.” “All right,” said the Cat; and this time it vanished quite slowly, beginning with the end of the tail, and ending with the grin, which remained some time after the rest of it had gone.