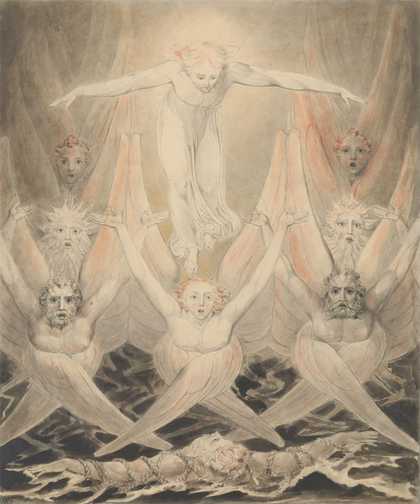

This display focuses on William Blake and several of his contemporaries. All artists used the human figure to explore

intense emotional states

In the eighteenth century, figure drawing was the basis of artistic training. Most of the artists in this room studied or taught at the Royal Academy of Arts, London. Students had to start by copying casts of ancient sculpture. Only later could they draw live models. Accurately depicting an observed figure was a prized skill. It was essential for painters of portraits and historical and narrative subjects.

These artists studied human form, movement, character and expression. But they applied this knowledge to unconventional, visionary scenes. Gods, heroes, demons and monsters populate their drawings and prints. These arose from their imaginations and from highly personal readings of myth, literature and history. As well as looking to the art of the past, they used topical incidents as inspiration. They caricatured, exaggerated and transformed contemporary public figures. The results are funny, grotesque and sometimes disturbing.