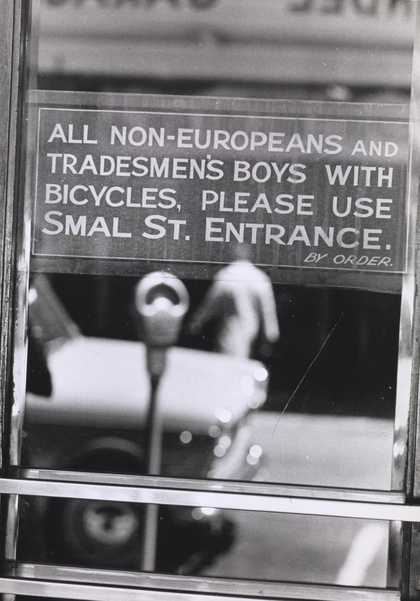

South African photographer Ernest Cole’s images document life for Black people during apartheid. Cole’s photographs are displayed alongside his photobook, House of Bondage

Born in South Africa in 1940, Cole was a self-taught photographer. He began his career at Drum magazine in 1958, before becoming a freelance photojournalist. His work primarily focuses on the lives of the Black community. Cole was working and living under apartheid in South Africa. This system of institutionalised racial segregation, underpinned by White minority rule, began in 1948. Anyone who was not classified as White was actively oppressed by the regime.

During apartheid, South African law divided its citizens into four racial groups: Black, White, Coloured and Indian. Officials used a variety of racist tests to classify people into groups. One of these was the pencil test, in which a pencil was pushed into an individual’s hair. If the pencil fell out, signalling that their hair was straight rather than curly, kinky or coily, the person was ‘classified’ as White. To pursue his work, Cole tricked the Race Classification Board. He straightened his hair and changed his name from Kole to Cole, in order to be classified as Coloured rather than Black. This allowed him to photograph the

experiences of Black people and travel more freely, but he was still at risk of arrest. He fled South Africa in 1966, taking many of his photographs and negatives with him.

As most of Cole’s photographs were used for press purposes, or taken for House of Bondage, he is not known to have used titles. Some of the works here featured in Cole’s photobook and are displayed with his descriptive captions. House of Bondage was first published in New York in 1967. Drawing attention to apartheid worldwide, the book was banned in South Africa. It continues to be a powerful visual testimony and archive of the stories and memories of the Black South African population during apartheid.

Art in this room