Edward Burra

Dancing Skeletons (1934)

Tate

Find out more about our exhibition at Tate Britain

Edward Burra

Dancing Skeletons (1934)

Tate

Edward Burra is renowned for his extraordinarily imaginative watercolour paintings. He pushed the boundaries of the medium to create bold, graphic works, rich in colour and detail. Burra’s compositions blend acute observations of the people and places he encountered with references from literature, art history, music, performance and cinema. His paintings are an intricate tapestry of influences, woven together with his idiosyncratic style.

Combining social realism and surrealist imaginings, Burra’s work engages with some of the 20th century’s most significant social, political and cultural events. His artistic imagination was fuelled by his extensive travels and appreciation of French, African American and Spanish cultures. Early paintings capture the hedonistic world of France during the ‘Roaring Twenties’ and the USA at the height of the Harlem Renaissance. Later, Burra’s experience of the outbreak of civil war in Spain and the Second World War in England resulted in macabre paintings full of violent imagery. He also produced inventive designs for performances on stage. Burra’s final body of work poetically chronicles the impact of post-war industrialisation on the British landscape.

Edward Burra (1905–1976) was born in London and lived most of his life at his family home near Rye, East Sussex. He was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis as a child and also had a blood condition which caused anaemia. His health shaped the course of his life and career. Encouraged by his parents, Burra pursued his interest in art, later calling painting ‘a kind of drug’ that helped relieve the pain. He studied in London at Chelsea Polytechnic and the Royal College of Art. At Chelsea, Burra formed lasting friendships with fellow students William ‘Billy’ Chappell, Barbara Ker-Seymer and Clover Pritchard. They remained close throughout their lives.

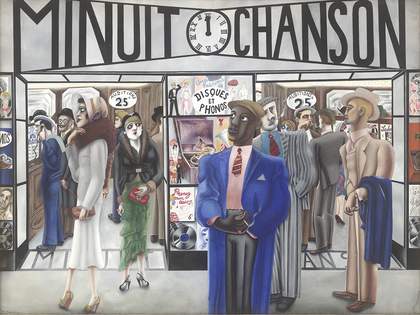

After art school, Burra and Chappell travelled to France. Drawn to the popular cultural entertainments in Paris, they visited museums and galleries, socialised in cafés and enjoyed the city’s pulsing nightlife. Burra and his friends also made several trips to the sunny south of France, visiting port cities and towns including Marseille, Toulon and Cassis. They frequented crowded markets, dockside cafés, bars and dance halls. Burra’s paintings capture the energy of the ‘Roaring Twenties’. The French called the decade ‘les Années folles’ (‘the crazy years’). It was a period of social and cultural liberation.

Burra drew inspiration from French literature, cinema and music. Like a magpie, he collected elements he liked and worked them into his paintings. He also incorporated memories of the places he visited and the people he saw, depicting them with an acute eye for detail. His imagination transformed these sources and recollections into satirical and surreal artworks.

Edward Burra Minuit Chanson 1931 Private Collection © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art Ltd., London. Photo: Lefevre Fine Art Ltd.

Burra was obsessed with music from a young age. He amassed an eclectic collection of gramophone records, which he listened to in his studio while he painted. Music became an integral part of Burra’s working practice. His artworks are infused with the rhythmic beat of his records.

Jazz gained worldwide popularity in the 1920s, and Burra was eager to experience the music live in its birthplace, the USA. In 1933, he travelled to the country for the first time. A free spirit, it is said he walked out of his family home one afternoon and disappeared without saying a word. His parents only discovered that he had visited the USA when he returned.

Burra stayed in New York City for several months. He frequented well-known bars, clubs and music halls in the neighbourhood of Harlem, including Club Hot-Cha, Apollo Theatre, and the Savoy Ballroom. These venues hosted many now-legendary musicians, from Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong to Cab Calloway and Billie Holiday. Harlem also attracted performers from other countries, such as the Lecuona Cuban Boys. Burra’s paintings from this time celebrate the exuberance of Harlem’s nightlife through his unique satirical style.

Burra returned to the USA throughout the 1930s and 1950s. As well as staying in New York, he spent time in Boston with the writer and poet Conrad Aiken. In 1937, Burra and Aiken travelled to Mexico, visiting Mexico City and Cuernavaca.

The music playing in this gallery has been chosen from Burra’s personal record collection, which is now held in the Tate Archive.

At the start of the twentieth century, many African Americans left the racial segregation of rural southern states in search of employment and better living standards in northern cities. The neighbourhood of Harlem in New York City became a centre for Black artists, writers, musicians, performers and academics. The period between 1917 and the 1930s became known as the Harlem Renaissance. New styles of music, dance, literature and art developed as artists worked across disciplines and blended African and European influences. In giving a voice to the African American experience and celebrating Black life, the movement contributed to the fight for civil rights.

The Harlem Renaissance was defined by the meteoric rise of jazz, with musicians achieving international recognition. Popular painters such as Aaron Douglas, Jacob Lawrence and Archibald Motley also depicted Harlem’s famed nightlife.

Burra was enamoured with Spanish culture. He avidly consumed Spanish art, literature and music and taught himself the language. His artworks conjured a fantasy of Spain, before he even visited the country.

Burra first travelled to Spain in 1933, visiting Barcelona, Granada and Seville. On his return to Rye, he produced paintings inspired by the cultural traditions he had seen. His strange depictions of Spanish governesses, known as duennas, were included in the International Surrealist Exhibition, which opened in London in June 1936. The exhibition sought to introduce surrealism to the UK. Burra’s paintings were shown alongside works by other artists exploring imagination, dreams and the unconscious mind. Though his art resonated with these surreal themes, Burra showed little interest in joining surrealist groups.

In April 1936, Burra returned to Spain, visiting Madrid. There, he witnessed the violent unrest that foreshadowed the Spanish Civil War:

One day when I was lunching with some Spanish friends, smoke kept blowing by the restaurant window. I asked where it came from. ‘Oh, it’s nothing’, someone answered with a shade of impatience, ‘it’s only a church being burnt!’ That made me feel sick. It was terrifying: constant strikes, churches on fire, and pent-up hatred everywhere.

Edward Burra

Burra fled Spain in July to escape the escalating hostilities. The Civil War marked a radical turning point in the artist’s practice and outlook. His paintings from the period chronicle the destruction of the war, drawing on newspaper articles filtered through Burra’s macabre imagination. Otherworldly demons and devils stalk ruined cities, conveying his nightmarish vision of the horrors of war.

The Spanish Civil War lasted from 1936 to 1939. It followed years of political instability across Europe. In Spain, tensions escalated after the monarchy was deposed in 1931 and replaced by a democratic Spanish Republic.

In 1936, the Popular Front, an alliance of left-leaning political groups, were elected to power. However, later that year, General Francisco Franco and other right-wing military leaders staged a coup aimed at establishing a fascist regime. A bloody civil war ensued across Spain. Those supporting the uprising were known as the Nationalists and received aid from fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Republican forces, or Loyalists, supported the left-leaning government. They rallied under the anti-fascist banner ‘¡No Pasarán!’ (‘they shall not pass’). Communists, socialists and trade unionists from across the world supported the Republican cause. Thousands of UK citizens volunteered to take up arms in the fight against fascism.

Around half a million people died during the war. Following the Nationalist victory, Franco established a dictatorship that lasted until he died in 1975.

The Second World War (1939–45) intensified a sense of tragedy that had been developing in Burra’s artworks. At home, on the south coast of England, Burra experienced the war first-hand. He witnessed heavy aerial bombardments, and the presence of Allied troops stationed in and around Rye before their deployment to the front.

Wartime restrictions left Burra increasingly isolated from his friends. He was also in pain due to rationing of medicine to treat his rheumatoid arthritis. His outlook, already changed by his experience of civil war in Spain, became darker still.

He wrote to Billy Chappell in 1945:

The very sight of peoples faces sickens me I’ve got no pity it realy is terrible sometimes Ime quite frightened at myself I think such awful things I get in such paroxysms of impotent venom I feel it must poison the atmosphere [sic]

Edward Burra

Burra’s few works from this period reflect his deep shock at the realities of war. They mark a change in the tone of his art. The satirical humour found in his earlier paintings gives way to more contemptuous portrayals of violence. He depicts soldiers as evil supernatural beings infiltrating the countryside around his hometown.

Edward Burra Soldiers at Rye 1941 Tate Presented by Studio 1942 © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art Ltd., London.

Burra’s passion for the stage remained constant throughout his life. His friend, photographer Barbara Ker-Seymer, recalled that as students, ‘we were … great ballet fans. We would queue for five hours for Ballets Russes tickets’. The Ballets Russes was a modernist ballet company founded in France. It profoundly influenced British artistic and theatrical practices. The company was known for creating all-encompassing artistic environments and blurring distinctions between art forms. Its radical approach resonated with Burra’s own.

Encouraged by his friendships with distinguished British dancers, choreographers and artistic directors, Burra started producing stage and costume designs in 1931. He frequently collaborated with his close friend Frederick Ashton, a renowned choreographer who later became Director of the Royal Ballet. Burra became a successful designer, working with the Royal Opera House, Sadler’s Wells and Ballet Rambert. He created immersive environments where performers could interact with their surroundings in authentic attire. Burra’s designs blend his characteristic style with influences from his travels in Britain and abroad, particularly in France, Spain and the USA.

Burra’s affinity with the stage shaped his approach to painting. Many of his works resemble stage sets and his figures often perform highly gestural poses.

The music playing in this gallery is taken from the ballets, operas and stage shows for which Burra created designs.

By the 1960s, Burra’s already frail health had begun to decline, making travelling abroad difficult. Instead, he embarked on driving tours of Britain with his sister Anne.

Burra observed fields, mountains and valleys as passing impressions through his car window. His attention was also caught by smog-belching power stations and collieries as well as newly built motorways, which had become a common feature of Britain’s changing landscapes. His sister would stop periodically so he could study the view intensely. Burra’s friend Billy Chappell sometimes joined them. Chappell was struck by the artist’s uncanny memory and eye for detail:

It fascinated me to watch Edward when the car halted by some especially splendid spread of hills, moorland, and deep valleys. He sat very still and his face appeared completely impassive … I do not remember Edward ever making any sort of note: not even the faintest scribble; yet weeks, even months later, the shapes, the tones; the actual atmosphere; and the colour of the clouded skies looming above those moors, hills, and valleys he had looked at so intently, would appear on paper.

Billy Chappell

Burra’s paintings reflect the impact of modern society on the British countryside. Ghosts and mythological beings haunt his landscapes, but many are desolate, devoid of life. These works convey the artist’s prescient concern for the destruction of the natural environment.

Even as his health declined, Burra continued painting to the end, driven by an unwavering commitment to his art. He died on 22 October 1976, aged 71, leaving behind a remarkable legacy of strange and surreal works that continue to captivate and inspire.