In addition to the display of works by Hogarth in the main collection, the artist has been the subject of a number of special exhibitions at Tate.

The first of these was in a period revival for the gallery immediately following the Second World War. The Tate was the main venue for exhibitions in a London short of space for such shows, which were mostly organised by the British Council and the newly formed Arts Council of Great Britain.

One of the most successful shows was the exhibition Masterpieces of English Painting – Hogarth, Constable, Turner, organised by the Tate, National Gallery and Victoria and Albert Museum as a touring exhibition and shown at the Art Institute of Chicago, 15 October – 15 December 1946.

It subsequently toured to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (closing there on 16 March 1947) and the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada (2 April – 11 May 1947) where it received a total of 76,575 visitors, the most for an exhibition since the gallery had opened in 1926.

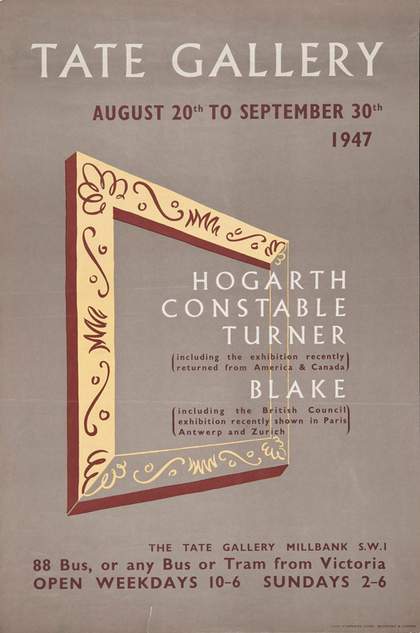

Poster for the exhibition Masterpieces of English Painting – Hogarth, Constable, Turner, Tate Library and Archive (TG 106-11)

The show retuned to London for display at the Tate from 20 August – 30 September 1947. It proved so popular that it was extended for a month, closing on 30 October 1947.

The Court Circular noted a visit to the exhibition by Queen Mary on 2 October, a short report in the Daily Telegraph the following day stating that,

Queen Mary spent over two hours looking at the special Hogarth, Turner and Constable exhibition. Incidentally, I hear it has been a great success. Attendances have averaged well over 5,000 daily.

By the 1 October over 135,000 visitors had been recorded, a remarkable figure in an age before the so-called ‘blockbuster’ exhibitions. The exhibition of Hogarth, Constable and Turner coincided with a British Council exhibition, also at Tate, of works by William Blake which had recently returned from a tour of continental Europe.

There was also a display of watercolours by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, as noted in the review, ‘Five British Artists’, by Eric Newton in The Times on 24 August 1947. Reflecting the prevailing attitude to British art at this time, he states that,

The Tate Gallery has never contained better evidence of the Britishness of British art than it does at present – Hogarth, Blake, Rossetti, Constable and Turner make an impressive series of names. They could have been produced only by a country with a strong literary tradition, a shamelessly romantic temperament and an amateurish but zealous attitude to the craft of painting.

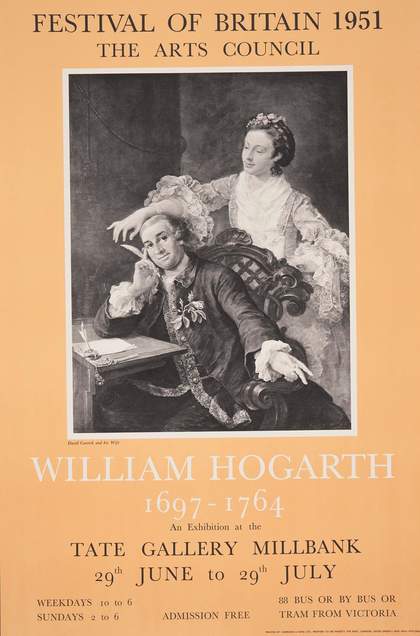

Poster for the William Hogarth exhibition at the Tate Gallery, 1951, Tate Library and Archive (TG 106-29)

Four years later in 1951 the Tate hosted the first solo exhibition of the work of Hogarth at the gallery, and the first monographic show on the artist since the one held at The British Institution in 1814. Open for one month, from 29 June to 29 July, it was organised by the Arts Council of Great Britain as part of the Festival of Britain. In his Foreword to the catalogue, Philip James, Art Director at the Arts Council, gave his reasons for choosing Hogarth to mark this event:

For the Festival of Britain the Arts Council is concentrating primarily on British Art, both of the present and the past. The choice of Hogarth to represent the Old Masters seems an appropriate one, especially so since, although in many senses he might be called a popular artist, no major single exhibition of his work has been held for the past 136 years. Hogarth is not only the first great native English easel-painter; his pictures epitomize perhaps more than any other the British character.

Curated by R.B. Beckett, the show contained 71 catalogued works, the first 13 being works on paper (a few of which were multiple works). The review in the Guardian (20 July 1951) was positive, calling the exhibition ‘a fine tribute to a Londoner of genius’, though it noted the absence of the painted modern moral series. A Rake’s Progress remained at the Sir John Soane Museum in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and Marriage A-la-Mode had been returned to the National Gallery the previous year.

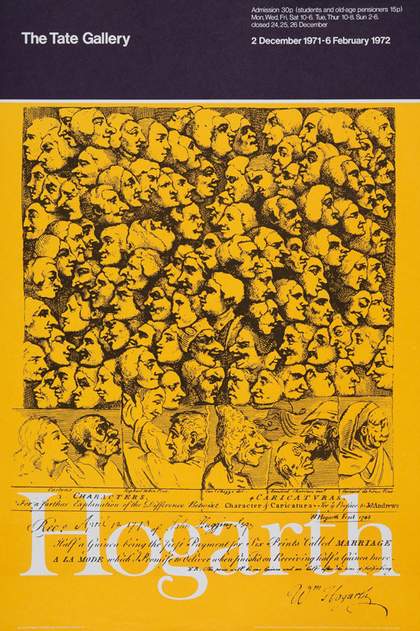

Poster for the Hogarth exhibition at Tate in 1971, Tate Library and Archive (TG 106-155)

It was a gap of exactly twenty years to the next Hogarth exhibition, held at the Tate Gallery from 2 December 1971 – 6 February 1972. It was curated by Lawrence Gowing, a former Keeper of British Art at Tate who was subsequently Professor of Fine Art at the University of Leeds, and comprised a total of 222 catalogued works.

The exhibition built on recent Hogarth scholarship, particularly the work of Professor Ronald Paulson, which had examined the life and career of the artist in much greater depth than previously, especially his activity as a printmaker, and positioned him within the context of his time. In his Foreword in the exhibition catalogue Norman Reid, Director of the Tate, noted that although Hogarth was one of the greatest English painters he had always been,

[a] rather awkward figure to cope with in the context of British art as a whole. In fact for some years now at the Tate Gallery he has been carefully isolated in a room of his own, albeit in his correct historical sequence and usually with every one of his pictures in the collection on view. At the same time his appeal to an audience far wider than the normal art-loving public has perhaps made him slightly suspect to the connoisseur and aesthete.

Installation shot from the Hogarth exhibition at Tate in 1971, Tate Library and Archive

Installation shot from the Hogarth exhibition at Tate in 1971, Tate Library and Archive

Installation shot from the Hogarth exhibition at Tate in 1971, Tate Library and Archive

Installation shot from the Hogarth exhibition at Tate in 1971, Tate Library and Archive

At this time the Tate did not have a dedicated exhibition space and used the Duveen Galleries for such shows. These large cavernous spaces, the central spine of the gallery today, were designed for the display of sculpture and required the construction of temporary walls and ceilings with lighting track to create the exhibition space.

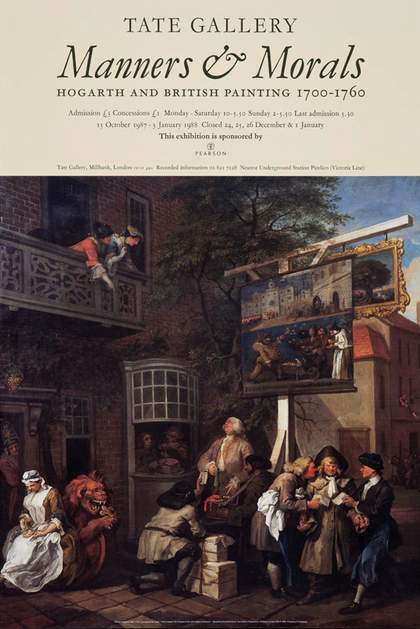

Poster for the Manners & Morals exhibition at Tate in 1987, Tate Library and Archive (TG 106-273)

In 1987 Elizabeth Einberg, Assistant Keeper of the British Collection at Tate and Hogarth scholar, curated the exhibition Manners & Morals – Hogarth and British Painting 1700-1760. The press release for the show indicates a different title - initially it was called Pomp, Virtue and Decorum - and the announcement goes on to say,

[t]he period lies comfortably within the lifespan of England’s first great native painter William Hogarth (1697-1764) whose response to and reactions against the prevailing canons of pomp, virtue and decorum in art did so much to set the artistic tenor of the period.

Though the title changed, the essence of the exhibition remained: a survey show of the period with Hogarth at its core. As noted by Marina Vaizey in her review of the show in the Sunday Times (18 October 1987), ‘Hogarth, naturally, is the star, although he was not so regarded in his lifetime.’

Installation shot from Manners & Morals exhibition at Tate in 1987, Tate Library and Archive

Installation shot from Manners & Morals exhibition at Tate in 1987, Tate Library and Archive

Hogarth was represented by 35 paintings, much more than any other artist in the show. These included iconic works such as the portrait of Thomas Coram and the Election series, but also a few works which were not included in the 1971 exhibition, such as Horace Walpole aged 10 and the portraits of Hannah Ranby and George Ranby.

It was held in the purpose built exhibition space occupying the north-east quadrant of the gallery, which had been designed by Richard Llewelyn Davies and opened in 1979.

Ten years later Elizabeth Einberg also curated the small exhibition Hogarth the Painter, held at the Tate Gallery from 4 March – 8 June 1997 to mark the 300th anniversary of the artist’s birth. The Tate paintings formed the bulk of the display with twenty works, the other eleven coming from important UK and Irish collections including The Royal Collection, the National Gallery and some private collections. These included works not shown in the previous Hogarth exhibitions, such as the portraits of George Parker, 2nd Earl of Macclesfield and an Unknown Gentleman in Grey, Holding Gloves, and displayed six paintings which were, in effect, new to Hogarth literature.

Installation shots from the exhibition Hogarth the Painter at Tate in 1997, Tate Library and Archive

Installation shots from the exhibition Hogarth the Painter at Tate in 1997, Tate Library and Archive

The year 2000 saw the birth of Tate Britain, as the Tate Gallery was renamed and reformed back to its original purpose as the National Gallery of British Art, with Tate Modern down the river at Bankside housing the modern foreign collection.

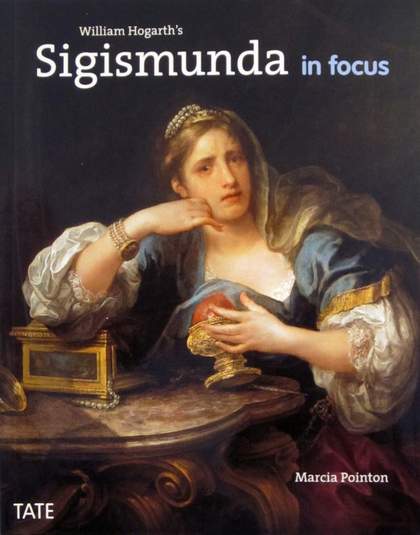

Cover of the book accompanying the display on Hogarth's Sigismunda at Tate Britain 2000, Tate Library and Archive

The new Director of Tate Britain, Stephen Deuchar, instigated a series of ‘in focus’ displays which aimed to ‘cast a fresh light on British works from the Tate Collections.’

The first of these was William Hogarth’s Sigismunda in focus, a one room free display examining one of Hogarth’s most controversial paintings.

Shown from 24 July – 4 November 2000 it was curated by Marcia Pointon, Pilkington Professor of Art History at Manchester University, described by Deuchar as, ‘one of the most vital forces in British art history for more than two decades.’

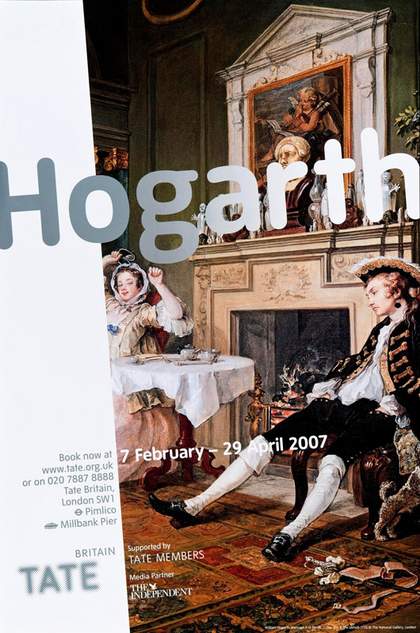

Poster accompanying the Hogarth exhibition at Tate Britain in 2007, Tate Library and Archive (TG 106-444)

The display was related to her Paul Mellon Lectures which were held at Tate Britain in the autumn of 2000, the title of the series being Brilliant Effects: Jewellery and its Image in English Visual Culture 1700-1800.

The third major Hogarth retrospective was held at Tate Britain in 2007. Curated by Christine Riding, Curator of Eighteenth and Nineteenth-Century British Art at Tate Britain, and Professor Mark Hallett of the University of York, the exhibition opened at the Musée du Louvre, Paris (18 October 2006 – 7January 2007) before its display in London at Tate Britain (7 February – 29 April 2007). It then travelled toSpain for display at Caixa Forum, Barcelona (30 May –26 August 2007).

The show was originally intended to be the first exhibition at the new Caixa Forum gallery which was being developed in Madrid (as indicated in the exhibition catalogue), but the revised completion date meant it was shown in their space in Barcelona instead. The tour to Paris and Barcelona marked the first major representation Hogarth in France and Spain.

Installation shot from the Hogarth exhibition at Tate Britain in 2007, Tate Library and Archive

Installation shot from the Hogarth exhibition at Tate Britain in 2007, Tate Library and Archive

Installation shot from the Hogarth exhibition at Tate Britain in 2007, Tate Library and Archive

Installation shot from the Hogarth exhibition at Tate Britain in 2007, Tate Library and Archive

In his Foreword to the catalogue Stephen Deuchar referred back to the observations of his predecessor Norman Reid in 1971 that Hogarth was a rather awkward figure in the context of British art. Deuchar noted how in the generation since then the artist had become less ‘suspect’, and that,

he seems today to have become naturally reintegrated within narratives of British art, not least because of the recent revolution in art history which has led us to think it normal, rather than eccentric, to consider works of art in intimate relationship to the complexities of the particular social world in which they were originally created.

Held in the Linbury Galleries (part of the Tate Centenary Development and opened in 2001), the exhibition was a huge success attracting a total of 176,859 visitors – placing it in the top ten exhibitions held at Tate Britain since it was launched in 2000.