© Tate (Matt Greenwood)

Introduction

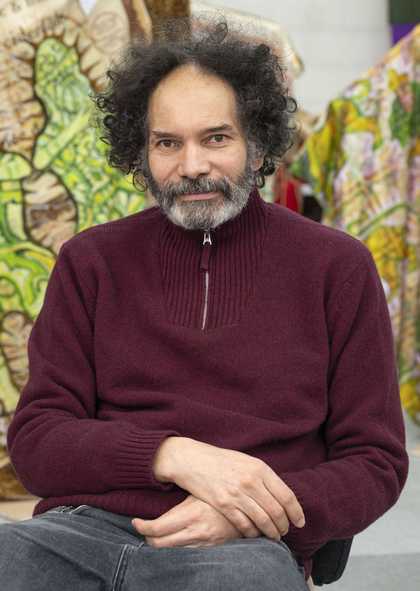

Though reflecting on history in many of his works, Hew Locke’s piece The Procession is not a history textbook. Rather, the artist considers it an ‘extended poem’, which incorporates and draws associations between contrasting ideas and imagery.

The installation adopts many of the references that Locke has been returning to throughout his career, such as medals from colonial military adventures and battles, instruments of financial and political power and memento mori.

The Procession also contains imagery from some of his previous works, including Cardboard Palace, 2002, commissioned by Chisenhale Gallery, London; drawings and paintings of Queen Elizabeth II part of Sovereign series started in 2005; his ongoing series Share, for which the artist reworks antique share certificates; and The Tourists, a 2015 intervention on-board HMS Belfast, commissioned by the Imperial War Museum.

Carnival

© Tate (Matt Greenwood)

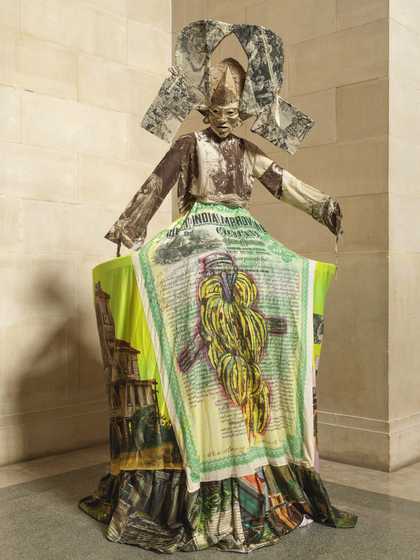

The influence of both Indian and Indo-Caribbean culture can be seen in The Procession, as in much of Locke’s work to date. It is unclear whether the procession participants are wearing masks or if these are their true faces. Several figures and costumes within The Procession reference specific Caribbean Carnival characters from across the region. These include Mother Sally in her voluminous dress, Midnight Robber, wearing a huge, brimmed hat, Pitchy Patchy, dressed in a suit made of tattered, colourful pieces of cloth, and Sailor Mas, inspired by British, French and American naval staff. Each has its histories, and its portrayal differs across the Caribbean.

Post-colonial trade

© Tate (Matt Greenwood)

The textile print on the front of this figure's dress reproduces one of the artist's works from his Share series.

Since 2009, Locke has collected and carefully reworked and painted over original share certificates for defunct companies. This particular share was for the West India Improvement Company. Based in Jamaica, it was formed in 1889 in New York to acquire and develop the Jamaica Railway and large areas of land on the island. Locke decorated the certificate with a bunch of bananas and, peeping out from behind it, the hands and head of the wooden figure of a bird-man spirit carved by the Taíno – Arawak people indigenous to the Caribbean. This is one of two Taíno sculptures in the collection of the British Museum. These pre-colonial carvings were discovered in Jamaica in 1792 and brought to the UK as part of a collection assembled by the nineteenth-century British art dealer William Ockleford Oldman. The Jamaican government has expressed its strong desire for their repatriation.

Another image is of the Fraser plantation house in Guyana, known locally as the 'House of a Thousand Windows'. Since childhood, Locke has admired these wooden buildings, part of a decaying, disappearing heritage.

Ghosts of Slavery

© Tate (Matt Greenwood)

This flag, held by a figure, includes photographs taken in the late nineteenth century of sugarcane cutters and workers loading bananas on a boat for export. Locke contrasts these with a share certificate for The Black Star Line.

This shipping company was co-founded by the Jamaican political activist and entrepreneur Marcus Garvey, who also founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in 1919. Though short-lived, the Black Star Line made a significant contribution to the Back-to-Africa movement and remains a symbol for Pan-Africanists. However, Garvey is a controversial and highly divisive figure, especially in relation to ideologies of racial separatism.

Additionally, the figure holding the flag is dressed in clothes with graphics of the ill-famed Brooks Slave Ship. Launched at Liverpool in 1781, it became infamous after these prints were published in 1788, showing the inhuman conditions in which enslaved people were kept onboard. Another pattern shows a tropical paradise, a long-lasting and clichéd representation of the Caribbean.

Environmental Disaster

© Tate (Matt Greenwood)

These figures appear to have struggled along their journey. Despite their formal clothing, the tidemarks on their trousers seem to suggest they waded through water or a flood. Many countries, including Guyana, are at risk of significant flooding due to global warming. Guyana’s agricultural coastal strip covers 10% of the land, houses 90% of the population, and is on average one meter below sea level. The Dutch reclaimed this land during the early colonial period, using slave labour to build a nation-spanning seawall, back-dam and canal system. The carried flag includes images of the land and architecture under threat – landscapes that Locke fears are being washed away in a literal flood of his childhood memories.

Monuments to Empire

© Tate (Matt Greenwood)

Much of Locke’s work to date has taken statues as a starting point and addressed colonial legacy. Growing up in Guyana, Locke remembers a shocking sight: the statue of Queen Victoria dumped at the back of the Botanical Gardens in Georgetown. That statue is reproduced on the flag carried by the abovementioned figures. It was commissioned in 1887 to mark the Queen’s Golden Jubilee, dynamited in 1954 as an anti-colonial protest, removed and dumped in 1970, re-erected in 1990 in front of the Supreme Court of Judicature in Georgetown, and defaced with red paint in 2018.

Revolution and Emancipation

© Tate (Joe Humprhys)

The two figures with the palanquin seem to carry with them their history. Their faces are covered with flowers and stars as if emerging from the rainforest. This grouping refers to the Haitian Revolution, the successful rebellion of self-liberated enslaved people against French colonial rule. The revolt ended in 1804 with Haiti’s independence.

The palanquin is made of fabric printed with fragments of John Singleton Copley’s The Death of Major Peirson, 6 January 1781 1873. This painting depicts the British defence of Jersey against the French Invasion. Prominently featured in the centre of the painting, and here decorating the clothing of an adjacent figure, is Peirson’s black servant, Pompey. The distinctive figure is seen avenging major Peirson’s killing. This symbolises the undivided loyalty of British colonies to the crown. The palanquin also features a section from the bottom-right corner of the painting, depicting women and children fleeing from the scene.

Inside the palanquin is a replica of one of Napoleon Bonaparte’s death masks. In 1794, slavery was abolished in all French colonies. However, Napoleon reinstated it in 1802.