Paula Rego The Artist in Her Studio 1993 Leeds Museums and Galleries (Leeds Art Gallery) U.K. / Bridgeman Images © Paula Rego

Room 1

a subversive vision

Paula Rego was born in Lisbon, Portugal, in 1935. At the time, the country was under a dictatorship, the Estado Novo (New State), which lasted until 1974. The authoritarian regime suppressed political freedom, forcefully maintained its colonies and drastically limited the rights of women. Rego’s parents, who were fiercely anti-fascist and Anglophile, wanted their daughter to live in a liberal country. At the age of 16, she was enrolled in a finishing school in Kent, England.

The following year, Rego went on to study painting at the Slade School of Fine Art, London (1952–6). Here she met and later married fellow painting student Victor Willing. After graduating, Rego lived between Britain and Portugal and settled in London in 1972.

Rego’s early paintings take inspiration from her own personal experiences, address the abuse of power and make women’s stories visible. In 1960, she started working with abstracted and visceral bodily forms. Works from this period often parody and denounce the grotesque nature of the Portuguese dictatorship and the brutality of its colonial occupations.

Room 2

Paula Rego

The Firemen of Alijo (1966)

Tate

Fragmented reality

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, Rego mainly produced collage-based works. She began this process by making drawings. She would cut these up, glue fragments on paper and add layers of paint and other drawings. Rather than using an easel, she worked on a table or on the floor. She relished this more tactile and intuitive way of working. In these works, Rego bears witness to injustice. She expresses her feelings of rage and anguish connected with world politics and events, from the cruelty of Portugal’s authoritarian regime to poor conditions for workers.

In her collages, Rego continues the surrealist tradition of combining disparate fragments and mixing fine art and popular culture. In 1965, she explained that her inspiration came from a wide range of sources: ‘caricature, newspaper articles, street events, proverbs, children’s songs, wheel dances, nightmares, wishes, fears.’ In 1974–5, she produced a series of illustrations of traditional Portuguese folk tales. As well as reflecting her interest in popular culture, the work is rooted in her experience of Jungian therapy. Rego had undergone this analysis herself. It awoke her desire to investigate archetypal characters that mirror and influence human behaviour.

Room 3

Paula Rego

Nanny, Small Bears and Bogeyman (1982)

Tate

fantasy and rebellion

Throughout the 1980s, Rego’s work developed significantly. She abandoned collage and began to make bold, richly coloured paintings with stark outlines. Animals that take on human characteristics, drawn in a caricature-like manner, begin to dominate her paintings. They provide a lighter tone for the artist to explore dark, emotional aspects of human relationships. The characters have a strong connection with the artist’s childhood memories and personal experiences.

From 1984, fiercely independent and rebellious girls become the main protagonists of Rego’s work. Rego’s girls revolt against coercive social norms and express female sexual desire. The characters also represent the artist’s inner world. Rego explained, ‘it was very important to go to the origin, the imaginative origin that provides the images of what we have inside us, without us knowing what it is’.

room 4

love, devotion, lust

Between 1986 and 1988, Rego completed a group of large paintings in acrylic, which are brought together in this room. In 1988, they were displayed in solo exhibitions in Lisbon and Porto, Portugal, and at the Serpentine Gallery, London. The shows cemented Rego’s reputation as a leading contemporary painter. At the time, she had not yet completed The Dance, so could not include it as she had hoped. The work features here in the way the artist intended, as the culmination of this body of work.

In these paintings, Rego addresses personal events, particularly her relationship with her husband, the painter Victor Willing. For many years, Willing had multiple sclerosis. He died in 1988, as Rego was working on The Dance.

Rego also investigates how women’s identities are shaped while growing up in patriarchal societies. She shows girls and young women interacting with animals and personal belongings, exploring a complex mix of ideas and emotions. These range from tenderness and sexual desire, to self-empowerment and emotional dependency.

Paula Rego

The Dance (1988)

Tate

Paula Rego

Drawing for ‘The Dance’ (1988)

Tate

Room 5

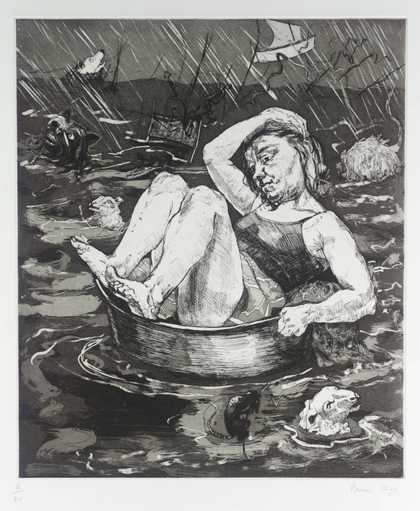

Paula Rego

Flood (1996)

Tate

characters at play

Rego’s fascination with storytelling has never faded. She has spent her life listening out for stories and turning them into pictures. The 1990s was a particularly productive period. Working in oil and acrylic paint, watercolour, and etching and aquatint, Rego took inspiration from a wide range of sources. Her series of Nursery Rhymes prints from 1989 illustrate traditional British children’s songs. Rego was delighted by the strangeness of these rhymes, which she highlights in her prints.

In works dedicated to Peter Pan, Pinocchio and Snow White, Rego delves into the darker side of children’s stories. She explores adults’ cruelty and children’s wildness, as they run away and embark on dangerous adventures. Literature has inspired Rego’s works across the decades, especially when the protagonists are young women, battling with their fears and desires. Included here is The Barn, which portrays the blunt physicality of Joyce Carol Oates’s gothic short story Haunted 1994. Also displayed is a large watercolour inspired by Thomas Hardy’s novel The Return of the Native 1878.

Paula Rego

Pendle Witches (1996)

Tate

Paula Rego

Him (1996)

Tate

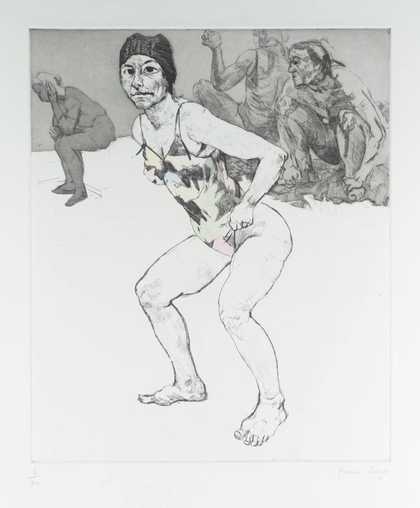

Room 6

infiltrating art history

In 1990, Rego became the first artist-in-residence at the National Gallery, London. She initially rejected the invitation but ultimately decided there was rich subject matter to explore in the collection. Rego went on to subvert the work of the mostly male artists who had operated in, and depicted, a world shaped by men, for men. She produced a number of works inspired by historical European painters such as Carlo Crivelli, William Hogarth and Diego Velázquez. Yet, in her paintings Rego inserts female characters. She revisits childhood memories and gives visual representation to the experience of women.

Room 7

Paula Rego

Bride (1994)

Tate

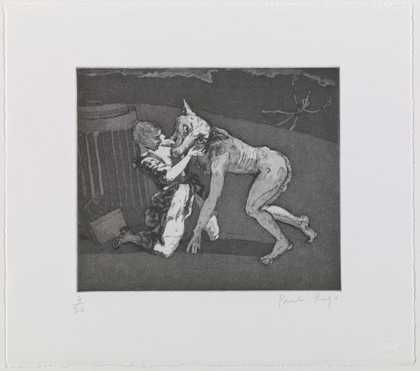

stories of women

In 1994, Rego embarked on a series of large pastels of single, female figures. There is nothing idealised or stereotypical about how Rego approaches her subjects. Her women are physically strong and have different temperaments. They might be desperately in pain, sexually aroused, or fiercely independent. They do not perform nor cater for the male gaze. The Dog Women series speaks of overwhelming, primal needs and emotions. Bride addresses sexuality as part of the marital contract. The pose in Target hints at a woman’s submissive stance and vulnerability.

In the Dog Women series, Rego started working regularly with Lila Nunes, her main model ever since. In Nunes, Rego found a collaborator and not just a sitter. At this time Rego also began to use pastel, which she has continued to favour. Sticks of pastel can be held in the hand rather than applied with a brush, so are more tactile and provide more immediacy. Rego likes the hardness of pastel, which can be built up and scratched through. She says, compared to a brush, ‘the stick is fiercer, much more aggressive’.

Room 8

coercion and defiance

Throughout her career, Rego has used her work to fight injustice. She raises questions about the social constructs that have historically enabled abuse towards women. This room brings together two influential series from the late 1990s. They each address different forms of abuse and struggle but also offer a defiant response. They also demonstrate Rego’s skill with her medium and her ability to stage intimate and convincing dramas in restricted domestic settings.

In 1998, Rego began work on a series of Untitled pastels, four of which are displayed here. They depict women in the aftermath of abortions they had to undergo illegally. The artist made those pastels following a Portuguese referendum in 1998 to legalise abortion, which was defeated by a narrow margin.

The Father Amaro series is inspired by the Portuguese realist novel The Crime of Father Amaro 1875, by José Maria de Eça de Queiroz. Rego portrays the women in the novel as victims of men’s abuse of power, but also as accomplices who want to preserve social norms.

Room 9

possession

In 2004, Rego asked her model Lila Nunes to pose for a series of large pastels titled Possession I–VII. It was inspired by late 19th century photographs of medical lectures showing women diagnosed with ‘hysteria’. This term was used to describe a wide range of psychological conditions, and has shaped prejudices about women’s assumed weak mental constitution. At the time, some believed hysteria to be ‘demonic possession’.

Rego found similarities between the images of those women diagnosed with hysteria and poses of female saints traditionally seen in Roman Catholic religious paintings. Possession represents a woman’s experience of both martyrdom and self-determination. Crucially, Rego empowers her subject through the expression of their sexuality.

Possession can also be read in relation to Rego’s own experience of depression and the process of healing through therapy, about which she has spoken openly. This experience is made more concrete in the series by the inclusion of the couch, which had previously been owned by Rego’s therapist.

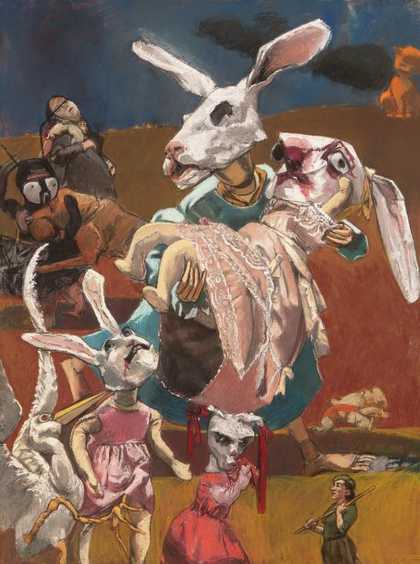

Room 10

Paula Rego

War (2003)

Tate

the theatre of life

All the artworks displayed in this room feature characters that Rego referred to as ‘dollies’. These are sculptures in textile, papier-mâché and other basic materials that Rego has been making since the 1960s. Since the early 2000s, they have become increasingly prominent characters in her works. She carefully stages a selection of them in her studio, alongside other objects, cloths and live models. She then draws the scene in pastel. Additionally, the works in this room, in explicit or enigmatic ways, return to distant memories of Rego’s native Portugal. Key themes include the spectres of dictatorship, the displacement of refugees and experiences of war.

Rego says: ‘I found that I got very involved in making props, in fact, creatures which I use as if they were people. They are people to me. And I find that more and more I am interested in doing that. Creating these creatures. And I mix them with people. I find it is quite important to have a person in there because it somehow emphasises the difference, and makes it more mysterious.’

Room 11

the pain of others

This final section brings together works addressing and denouncing different forms of abuse: the trafficking of women and female genital mutilation. Rego made these works in response to the numerous stories of this kind of abuse that she read in the news. In doing so, she gives visibility to the pain of others, namely the children and women that undergo this abuse. She also represents the close and complex relationship between victims and perpetrators.

Rego is an artist who has consistently made work that responds to and fights injustice. In keeping with this lifelong concern, we end this retrospective exhibition with this group of powerful, harrowing works that serve as a provocation for action. Rego’s and our wish is that there might be an Escape, and more justice for all women.