John Piper

Abstract I (1935)

Tate

John Piper (1903–1992) is one of the most significant British artists of the twentieth-century. From an early age, he made drawings while journeying around the country, developing a love and historical knowledge of the British landscape, its buildings and monuments. Renowned for powerful and romantic paintings of this landscape and views of churches and monuments, Piper worked across an extraordinarily diverse range of artistic disciplines.

Piper was a paradox – an antiquarian with an interest in medieval history and antiquity yet also a major advocate of international abstract art in Britain. In the early to mid-1930s, he became closely acquainted with artists based in Paris such as Alexander Calder and Jean Hélion, which further informed his developing modern art aesthetic. His coastal collages harness the influence of Picasso while capturing the atmosphere of the English coastline, and his works depicting archaeological sites are at once ancient and modern. Likewise his enthusiasm for medieval stained glass found expression in the dynamic interplay of crisp colour planes found in his abstract paintings. Highlighting this rich interplay of influences, the exhibition includes works by Paris-based artists, to illuminate how Piper looked beyond these shores for inspiration towards forging a distinctive national art style.

As an official war artist, Piper created some of his most sombre and vital works recording the damage sustained by historic buildings and monuments. During the 1940s his work evolved to embrace a style of painting informed by artists of the romantic era including JMW Turner that retained many of the visual innovations developed in his 1930s abstract period. After the war, Piper received many public and applied arts commissions. Of all of these, his major stained glass window designs including for Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral had the closest relationship with his painterly practice, signalling the productive convergence of his interests in art, architecture, the church, and the regeneration of heritage traditions in the modern era.

Curated by Darren Pih, Exhibitions & Displays Curator, with Tamar Hemmes, Assistant Curator

EARLY PAINTING AND COLLAGE

From an early age, Piper made drawings during his travels to locations within striking distance of his home in rural Surrey. Drawing and writing would remain central to his serious minded attitude to travel, providing the foundation for his artistic sensibilities while encouraging his scholarly interests in his native landscape and architectural history.

While determined to become an artist, his entry into art school was delayed as his father expected him to study law and enter the family firm of solicitors. However his father's death in 1927 freed him to enter the Richmond School of Art, before enrolling at the Royal College of Art the following year. Piper's landscapes and still lifes from this period have a self-consciously naïve paint-handling that affectionately captures the character of the depicted scene.

The period 1927 to 1933 was one of fervent experimentation for Piper, during which he developed a reputation as an art and theatre critic. He continued painting while becoming attuned to the trajectory of the modern movement as it developed in Britain. This convergence of interests is seen in his coastal paintings of 1933, whose pictorial elements are linked by a sinuous line showing the influence of Jean Arp and Georges Braque. His admiration for Picasso led him to create still life and coastal landscapes using collaged coloured and printed papers with paint and ink. These demonstrate Piper's admiration for the cubist layering of pictorial space as a collage technique. At the same time, they focus on a distinctively English subject matter such as a scene from a coastal tea rooms, using paper doily as a collage element to depict net curtains.

PHOTOGRAPHY AND SHELL GUIDES

Piper's interest in drawing blossomed alongside his love of travel and learning about new places. One of his earliest creative endeavours is an account of a tour made from the Cotswolds to East Anglia. This travel diary contains descriptions of buildings accompanied by his annotated ink drawings and photographs. Compiled in 1921 when he was seventeen, it provided a blueprint for sketchbooks made throughout his life.

His interest in photography and scholarly appreciation of the British landscape and its history led to his involvement with the Shell Guides to the British counties, published after 1934 on a county-by-county basis under the editorial control of John Betjeman. Piper became its co-editor in 1949. The Shell Guides encouraged a new breed of motorist to explore places of interest, helping ferment a romantic sense of Britain by drawing attention to what was distinctive or peculiar to each county. Piper's guide to Oxfordshire (or Oxon, as it was titled) was first published in 1938. This room contains a selection of Piper's sketchbooks and Shell Guides alongside a slideshow of his photographs, taken during commissions for magazine articles or for his own research interests.

GOING MODERN

Piper's embrace of abstract art reflects a wider tendency in the 1930s to evolve a distinctive British strand of modernism. In 1934, Piper was elected to the Seven and Five Society. Founded in 1919 as a traditional exhibiting group, it underwent a radical and progressive transformation in the 1930s under the leadership of Ben Nicholson to become the abstract-constructivist wing of British art. At the same time, Piper supported the ambitions of Myfanwy Evans, his partner and future wife, to launch and edit AXIS: A Quarterly Review of “Abstract” Painting & Sculpture. Published between 1935 and 1937, it was the first magazine in Britain devoted to international abstract art.

Motivated by his growing interest in modern art, in June 1934 Piper travelled to Paris, visiting the studios of artists including Jean Hélion, Alexander Calder and Cesar Domela. Following this visit, Piper began making his abstract constructions and paintings. He also experimented with the modern style to create works depicting bathers. These works demonstrate the influence of the Parisian avant-garde with which Piper had become acquainted. The use of colour, however, corresponds to that found in his earlier work and, although abstract, the paintings retain figurative and representational elements connected to the English landscape.

Piper would soon move on from abstraction, writing to Nicholson in May 1936 to disassociate himself from the Seven and Five Society. While abstraction had been a meaningful and useful exercise, he came to regard it as inadequate in recording and understanding landscape and architecture.

ABSTRACTIONS FOR ARCHITECTURE

In May 1938 Piper exhibited paintings of coastal collages alongside abstracts at the London Gallery, publicly signalling his return to the landscape as his primary subject matter. Yet at this moment his abstract works began to attract the interest of architects and interior designers. That year Piper was commissioned to produce a mural for a modernist apartment at the Berthold Lubetkin-designed Highpoint Two in London. The large-scale mural and his related painting Black Ground (Screen for the Sea) 1938 marks the culmination of his abstract period and points towards the series of public-realm commissions which were a preoccupation after the Second World War.

Piper's wider interests in literature, music and theatre led to him being asked to design for the stage. His first commission was for 1938's Trial of a Judge, directed by Stephen Spender. Piper's design effectively transformed one of his abstract paintings into a stage set of hard-edge geometrical theatre flats painted with bold primary colours. Piper's modern design resembled Mondrian's Parisian studio which Myfanwy had visited in 1934. The commission led to a fruitful series of further collaborations with directors and choreographers after the war, including his long-running association with the conductor and composer Benjamin Britten.

THE POST-WAR LANDSCAPE

Piper's art between 1940 until the early 1950s speaks of a wider revival of interest in the art and ideas of the eighteenth-century Romantic period, which emphasised emotion and individualism while glorying in the past and in nature. This introspective post-war mood propelled Piper and other artists and writers towards an imaginative regeneration of English art by focusing on its landscape, heritage and traditions.

In these years Piper became established as an emblematic British landscape painter. His depictions of the mountains of North Wales and other locations often exude an otherworldly intensity of mood. By painting outdoors, Piper experienced the magnificence of the sublime through a direct encounter with mountains. His paintings made after the 1950s deploy a bold use of colour and decorative flourishes, suggesting he was looking again at the work of Matisse and Braque.

After the mid-1950s, Piper's painting fell out of fashion with art world tastes. In this period, however, he began to receive high-profile commissions to design stained glass for churches and cathedrals in Coventry and Liverpool, as well as murals that helped regenerate the landscape of post-war Britain. These commissions required him to collaborate with craftsmen and develop new approaches to subject matter and traditional methods of making art. He also received commissions for fabric, textile and wallpaper designs.

LANDSCAPE COLLAGES (1936–8)

In 1936, following his foray into abstract art, Piper returned to making representational collages based on familiar coastal and landscape subjects. Compared to the collages of 1933-4, this second group are looser in style and summarise the subject in a lively spontaneous manner. In 1938, Piper wrote of finding inspiration in the 'magnificent wreckage' of the seaweed, driftwood and objects found washed up on the beach. 'Whatever direction you look… is worthy of contemporary painting. Pure abstraction is undernourished. It should at least be allowed to feed on a bare beach with tins and broken bottles.'

Many make expressive use of grey and deep blue, suggesting extreme coastal weather effects. The works were created out-of-doors, often in inclement conditions during his travels to the Kent and Sussex coast, as well as at locations in Wales and Ireland. Armed with a bag of coloured papers, inks and brightly hued gouache paints, he made the works on the spot, cutting, tearing and gluing the paper to the picture surface. Perhaps more so than in other works, the collages demonstrate the freeing influence of Picasso through their spontaneous expression and economical use of pigment.

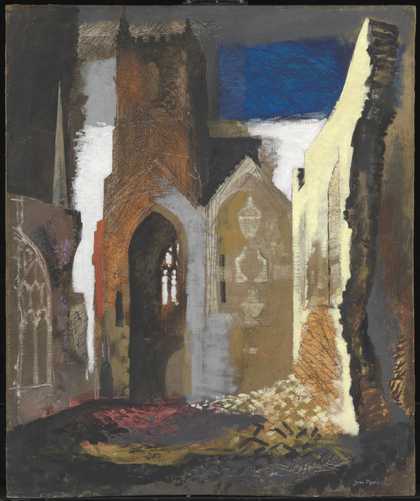

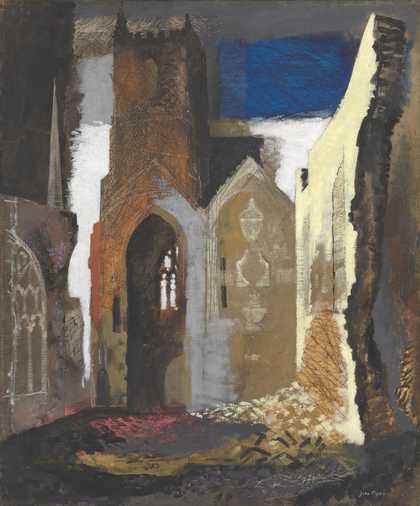

WAR ARTIST

In late 1939, Kenneth Clark founded the 'Recording Britain' scheme. This employed artists to create watercolour paintings in response to the looming threat posed to the nation's architectural heritage by the Second World War and – what seemed to some – the pace of industrial development in England. Piper's involvement with the scheme gave way to him becoming an official war artist. In April 1940 he was commissioned to make paintings at the Air Raid Precautions Control Room in Bristol. Receiving his orders verbally to avoid any documentation, he travelled to the top-secret location with its underground corridors and rooms.

As a war artist, Piper was granted a 'sketching permit' and a fuel allocation, enabling him to travel around the country to fulfil commissions. That summer he travelled with Myfanwy to locations on the South Coast, Wales and Yorkshire to create paintings of historic houses and ruined abbeys. These works retain elements of the crisp modern style of his mid-1930s abstracts. For Piper however it was more apt to look to the entire history of British art and to a sense of shared heritage, in order to create a more representational art that was emotionally meaningful.

Following the Blitz in September 1940, Piper was asked to begin recording bombed churches, and many of his paintings from this period have a sombre tone reflecting the circumstances. Piper's pictures of damaged churches are always unpopulated, creating a sense of stillness and quiet; their emotional charge stems in part from depicting an interior or private spiritual space which is exposed to the elements. Piper's experience as a war artist affirmed his commitment to the British landscape as his primary subject, one which sustained him for the remainder of his career.

ENGLAND’S EARLY SCULPTORS

In the same way that medieval stained glass informed the language of his abstract paintings, Anglo-Saxon and Romanesque stone carving influenced Piper's artistic practice. In 1936 his interest in churches led to him being involved in a British Museum programme to research and obtain photographic documentation of early English carved fonts, crosses and other stone fragments from across Britain. Armed with a paraffin lamp and a Brownie box camera, he and Myfanwy travelled through Herefordshire, Anglesey, Dorset and Yorkshire in search of isolated carvings.

In October 1936, he contributed an article entitled 'England's Early Sculptors' to Architectural Review. His illustrated text proposed a lineage between this ancient native tradition and 1930s modern art, stating 'the purely non-figurative artists of some early Northumbrian and Cornish crosses were the forbears of the pure abstractionists of today'. Piper's text remains a milestone in the history of reappraising and appreciating early English carving. At a time of debate into artistic styles, such as the struggle to reconcile surrealism and abstraction, Piper looked beyond his own time to reveal links between the ancient and the modern.