Rotimi Fani-Kayode

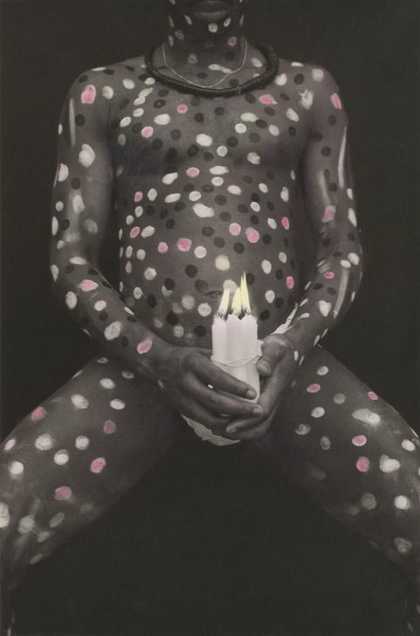

Sonponnoi (1987, printed c.1987–8)

Tate

When you walk through the conventional art gallery, you will find scintillating portraits of white women laying in the nude. The objectification of the white woman's body is a subject of continued practice and interest for an industry historically dominated by white men. This objectification of the body has extended to other people and communities, like Black people and people of colour.

To refute reductive and limiting representations of their bodies, sexualities and lives, a number of artists have dismantled and disputed the commonality of such images by portraying nudity and sexuality through their own eyes. These artists, often from marginalised communities, present their renderings of the human form in a way that reclaims the historic narratives held over their bodies.

There is much to learn in these artworks. They can be educational in the stories they tell about sexuality. They can be inspirational in depicting the body as desirable outside of the white gaze. They can be empowering by showing the multitude of ways we can love.

As part of From a Place of Love, a collaboration between Tate Exchange and UK Black Pride, we asked four members from the queer Black community to speak about some of the artworks in Tate’s collection that resonated with them. Watch them in conversation in At Home in Our Bodies and read on to find out in more detail about some relevant works of art in the collection.

Marc Thompson (he/him) is the director of The Love Tank, a not-for-profit community interest community that promotes the health and wellbeing of underserved communities through education, capacity building and research. Marc is also the co-founder of Prepster and BlackoutUK.

MisSa (she/her) is an iconic variety star, internationally recognised sword swallower, singer, poet and exhibited artist. MisSa, one of four Black sword swallowers world wide, was the first to perform at the legendary Burlesque Hall of Fame in Las Vegas. She is currently performing her own solo show Black Sheep.

Remi Arnold (they/them) is a person-centred counsellor working at cliniQ, an award winning trans lead sexual health and wellbeing service.

Mwice-Margaret Kavindele (Sadie Sinner) (she/her) is a velvet-toned songbird or powerhouse of a host. Sadie Sinner is a creative force! Founder and curator of The Cocoa Butter Club, Mwice is here to decolonise and moisturise stages across the globe.

Rotimi Fani-Kayode

Rotimi Fani-Kayode was a Nigerian photographer who explored racial tensions and sexuality through portraiture. He moved to England at the age of 12 to escape the Nigerian Civil War. His work often considers his Yoruba ancestral heritage alongside themes of eroticsm and his homosexuality.

‘As a Black gay male artist, Black British Nigerian, he is part of the canon we don’t talk about very often. A lot of his work is produced in the mid 80s when the HIV epidemic is taking hold and Rotimi is a victim of that as well, so I honour him and hold him up because I think we need to remember these brothers who passed away.’ - Marc Thompson

Sonponnoi is named after the Yoruba orisha or spirit responsible for smallpox. The Yoruba people believe that by speaking his name, a smallpox outbreak would ensue. Fani-Kayode relies on this taboo within his work to speak about his own sexuality. The subject of his image is covered in painted spots that signify smallpox. The subject is also nude, using a burning candle to cover his genitalia. The image reflects the othering that occurs when sexuality deviates from normalised heteronormativity. The metaphor of the candle is that it continues to burn even in the situation of sickness, be that smallpox or homosexuality which has been equated by homophobes to a disease.

‘I look at all the dots and I kind of saw myself in it. And I thought every dot on this body was a sexual partner throughout my life. Every person I have had sex with has left a mark, on my soul, on my physical body, on my development’ - MisSa

Zanele Muholi

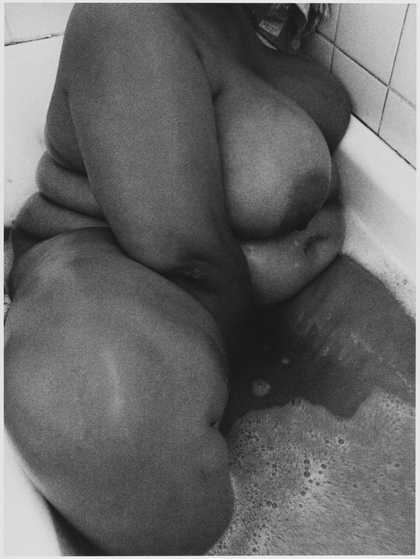

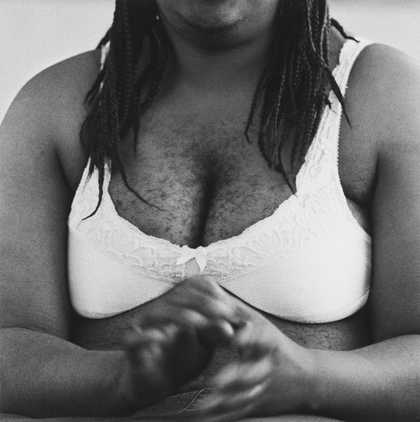

‘I love this piece because it looks like my body’ - Mwice-Margaret Kavindele

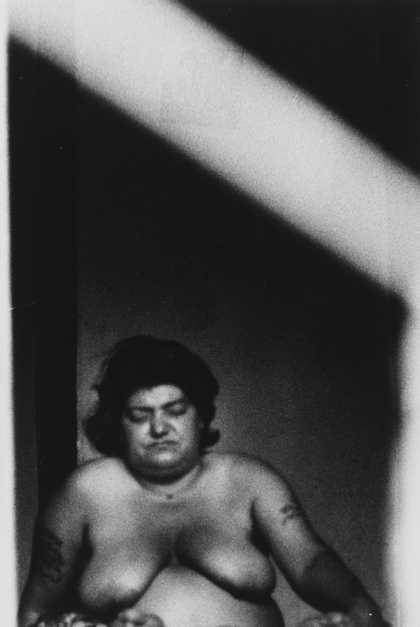

Zanele Muholi describes themself as a visual activist. From the early 2000s, they have documented and celebrated the lives of South Africa’s Black lesbian, gay, trans, queer and intersex communities. In the series Only Half the Picture, Muholi confronts the stereotypes faced by the Black LGBTQIA+ community in South Africa. Their work reframes the Black body, so it is not fetishised by a white gaze.

In each of these photographs the person’s head is either totally or partially cropped out of the image. The images are intimate, close-up and respectful. The focus is on the full variety of bodies, their postures and actions; beauty and suffering co-exist in these photographs. The identities of the subjects are concealed, and their dignity and privacy left intact. When nudity is depicted, it is never objectification. Muholi refers to the people in their images as participants rather than as subjects. Yet the intimacy of these images remains intact and they show sexual vulnerability to the viewer.

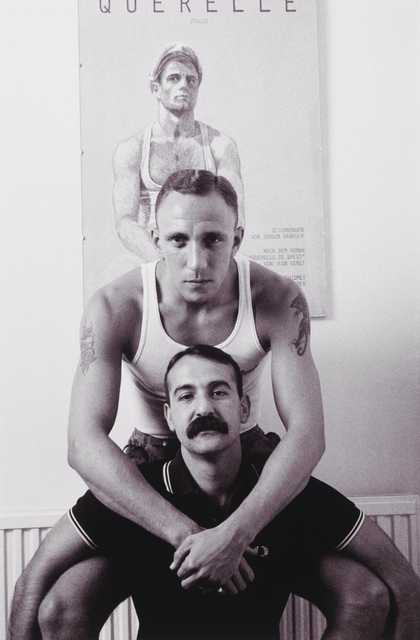

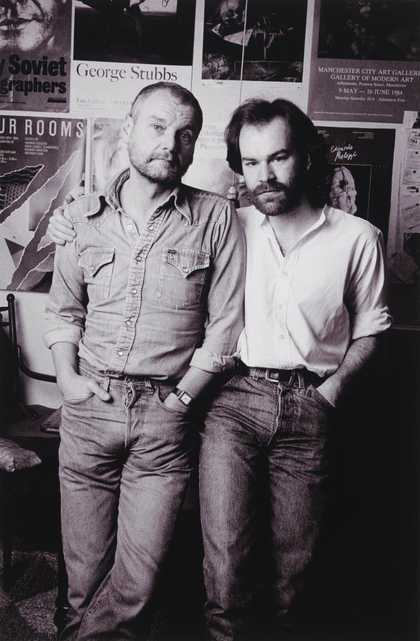

Sunil Gupta

Sunil Gupta

Ian & Pavlik, London (1984, printed 2018)

Tate

Sunil Gupta

Lisa & Emily, London (1984, printed 2018)

Tate

Sunil Gupta

Emmanuel & David, London (1984, printed 2018)

Tate

Lovers: Ten Years On was made after Sunil Gupta’s own ten-year relationship ended and, as a form of social analysis, he decided to document the long-term gay relationships he encountered. The series is also a response to the shift in public opinion around homosexuality in the wake of the HIV and AIDS crisis. Most of the subjects are Gupta’s friends in the Greater London area. Taken over a period of two years, the black and white portraits all follow the same format – they are shot in domestic interiors, the poses and arrangements reminiscent of traditional family photographs.

'Couples seem to have come into their own. Gay self-help groups encourage a change in sexual behaviour and a reduction in the number of partners. However, still without legal recognition, with the new emphasis on monogamy, with social attitudes reverting to hostility and given the visibility of day-to-day life for gay men within relationships, being a partner now can prove to be as difficult as it was a decade ago.' - Sunil Gupta

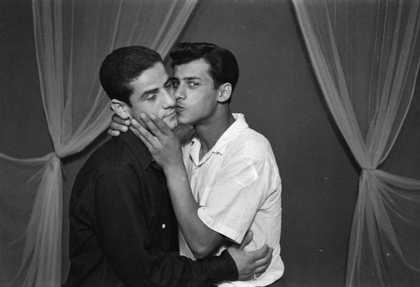

Akram Zaatari

Akram Zaatari's collection of images does something similar to Gupta. All of the photographs were taken by the Lebanese commercial photographer Hashem el Madani between 1948 and 1982 and compiled into the present group by Zaatari. This series of photographs include pairs in homes. They show tender moments of love that challenge gender and sexual conventions. The romantic pairings are normalised by situating them in domestic spaces. Almost all of the sitters assume poses deliberately for the camera, sometimes accompanied by props or costumes, and most gaze directly towards the lens. Many of the pictures show subjects interacting in various ways, including embracing, kissing and acting out scenes.

‘When we talk about sexual health, we don’t talk about how does it feel to be touched.’ - Remi Arnold

Tracey Emin

Tracey Emin

Is Anal Sex Legal (1998)

Tate

Is Anal Sex Legal? refers to the vague Victorian ruling against homosexuality (the Labouchere Amendment of 1885) which made no direct reference to anal sex, but to ‘gross indecency’. Although it has been historically taboo, no legal rulings have ever been specifically directed against heterosexual anal sex. Much of Tracey Emin’s work describes sex graphically in words and images, breaking down the binary between the public and private. Asking questions about sex should not be taboo. She says:

It can often be painful; it feels like a violation. But if you love someone and that’s what you’re really into, you feel brilliant...I had one relationship which was all about that. In the years I was with him I think I only had vaginal sex twice ... Women are not allowed to enjoy anal sex. Well, a lot of women are never going to get it because they are not ready to accept the fact that they like it. They’ve probably never been with a partner who would face up to wanting it. A lot of people don’t know how to do it properly, that’s the other thing. But my Nan told me it used to be the major form of contraception. I’m sure that 100 years ago it wasn’t a problem. - Tracey Emin

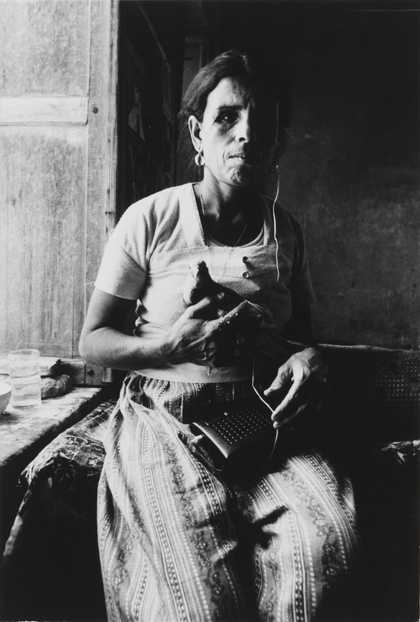

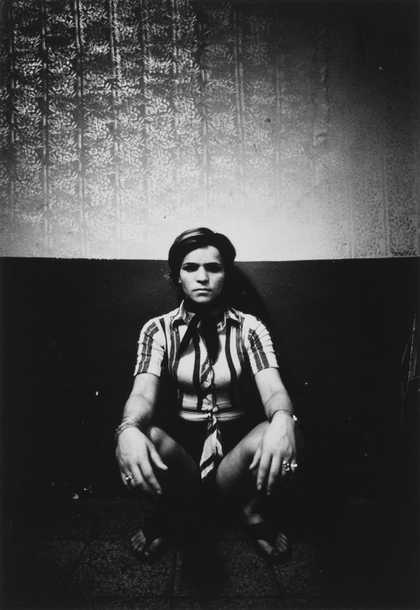

Kaveh Golestan

Kaveh Golestan

Untitled, Prostitute Series (1975–7)

Tate

Kaveh Golestan

Untitled, Prostitute Series (1975–7)

Tate

Kaveh Golestan

Untitled, Prostitute Series (1975–7)

Tate

Prostitute Series (1975-1977) are portraits of sex workers by Iranian photographer Kaveh Golestan. They were taken in the Citadel of Shahr-e No, the red light ghetto of Tehran. In 1980, a few years after this series was taken, the government demolished the area. Around 1,500 women had been employed in the area. It now stands as a park and hospital.

Each of these women have their own story. Golestan’s work examines how sex workers are treated by society. Punishment is severe in Iran, but regressive attitudes around sex work exist across the globe. Golestan’s black and white images contradict the performative nature of such violence that is meant to publicly shame. A government survey in 2009 found that over half of husbands privately supported their wives who were sex workers. The photographs show these women often looking directly down the camera lens directly at the viewer in an act of empowerment.

From a Place of Love

From a Place of Love is a programme developed by Tate Exchange and UK Black Pride in response to an exhibition of Zanele Muholi's artworks. Tate Exchange is exploring love in a year-long consideration that rethinks the issues facing our society today. As part of their fifteenth birthday celebrations, UK Black Pride are exploring home. From a Place of Love brings these two themes together with a programme that centres voices from the QTIPOC community.