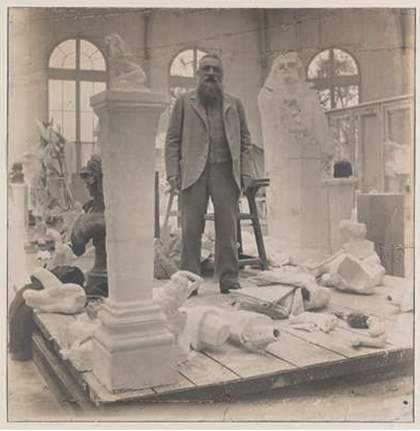

Rodin in his studio in Meudon c.1902. Photo by Eugène Druet, Musée Rodin

Room 1

THE AGE OF BRONZE

I began as an artisan to become an artist. That is the good, the only, method.

Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) was born in Mouffetard, a working-class district of Paris, the son of a police inspector. After repeated rejection from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, he worked as a studio assistant for many years.

Rodin was in his mid-30s and relatively unknown when he started work on The Age of Bronze. Its life-like realism caused an immediate stir. He modelled the figure in clay, working by close observation and examining his subject – a young Belgian soldier called Auguste Neyt – from all angles, even from above. However, when the sculpture was first exhibited, it was so realistic that Rodin was accused of having made the cast directly from the subject’s body instead of sculpting the figure by hand.

Offended by allegations of cheating, Rodin commissioned photographs of Neyt to demonstrate the subtle anatomical differences between the sitter and the sculpture. The accusation had a major impact on Rodin. He soon broke with the conventions of classical sculpture and idealised beauty. Instead, he would create new images of the human body that reflected the ruptures, complexities and uncertainties of the modern age.

Room 2

The EY Exhibition: The Making of Rodin offers a unique focus on Rodin’s work in plaster. Exploring Rodin’s approach to making, it looks at his creative use of fragmentation, multiplication, repetition, enlargement and assembling disparate elements.

It takes inspiration from the major survey exhibition that Rodin staged in 1900 in a specially constructed pavilion at the Place de l’Alma in central Paris. With sculptures from throughout his career clustered around the space, it was like walking through the artist’s studio. This impression was reinforced by Rodin’s decision to exhibit plaster versions of his work, rather than the marble or bronze casts that he was best known for.

Rodin worked principally by modelling in clay, a malleable material that needs to be kept damp in order to remain soft. Until he could afford to hire assistants, his lifelong partner, Rose Beuret, would help him with this task. It was only after he enjoyed a degree of commercial success that Rodin could afford to have multiple plaster casts made of his clay models. These allowed him to alter and revise his works many times.

Despite taking centre stage in Rodin’s own exhibition, the plaster casts were not recognised as being as important as the works in more traditional materials until well into the twentieth century. Yet with their emphasis on process, materiality and creative accident rather than perfect finish, they continue to mark a threshold moment in the history of modern sculpture.

Patience is also a form of action.

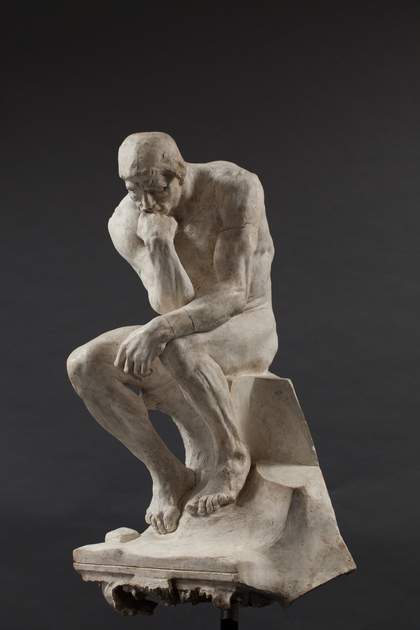

Auguste Rodin The Thinker 1903 Albertinum/ Skulpturensammlung, Inv. Abg.-ZV 2627(ASN 4817). Purchased at the Art Exhibition, Dresden, 1904; donated by a private citizen (Fritz Emil Günther).

Auguste Rodin Etude pour le Penseur 1881 Musée Rodin, S.01168

The Thinker

The Thinker was originally conceived as part of The Gates of Hell, monumental bronze doors commissioned for a proposed Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris. This was Rodin’s first major government commission. He planned an assembly of 180 figures inspired by Dante Alighieri’s poem Inferno. Ultimately, plans for the museum fell through and The Gates were never completed. However, it became the defining project of Rodin’s career, providing him with a storehouse of figures to rework, rearrange and repurpose.

In 1888, Rodin developed The Thinker as an independent work. Like most of his sculptures, it was originally modelled in clay, then cast in plaster. The resulting form could be copied, enlarged to monumental size, and transposed to bronze or marble.

Rodin never replicated the exact physical proportions of his models, and these differences became even more pronounced when the sculpture was enlarged. The Thinker’s foot was later presented as a work in its own right, mounted on a decorative plaster pedestal.

The Walking Man

Rodin composed The Walking Man from two separate studies that he made for the sculpture Saint John the Baptist Preaching. The torso from one study was joined to the legs from a different model. He happily accepted the contrast between the smooth surface of the legs and the cracked surface of the older torso.

Between 1905 and 1907 the sculpture was enlarged using a pantograph. This was a device for reproducing three-dimensional objects at different scales. A specialist technician, Henri Lebossé, ran these operations at his own studio.

The original object is placed on one rotating table, and a block of material such as modelling clay or soft plaster on another. An articulated boom is mounted above, with two points adjusted to the required ratio for enlargement or reduction. The operator follows the contours of the model. The first point and its movements are mechanically reproduced by the other point, which marks the soft material with a modelling tool.

Large, complex sculptures were taken apart and worked on one piece at a time. The torso and legs of The Walking Man, for example, were enlarged separately and then reassembled.

Whiteness

The whiteness of the plaster figures is often seen to relate to the marble sculpture of ancient Greece and Rome. This emphasis on white originated from a widespread misunderstanding of classical sculpture first described by the German archaeologist Johann Winckelmann (1717–1768). For Winckelmann, these idealised, marble-white bodies represented the pinnacle of European civilization. Winckelmann’s writings were highly influential on the emerging discipline of art history. This privileged the allegedly superior artistic achievements of Europe, often to the detriment of other cultures.

There was growing awareness in the nineteenth century that classical Greek sculptures were originally painted, and had been colourful and much more lifelike. Yet, many sculptors, including Rodin, continued to adopt the convention of classical sculpture as white to make a link between their work and the art of the past. This mistaken belief in the whiteness of ancient Greek statues persists even today.

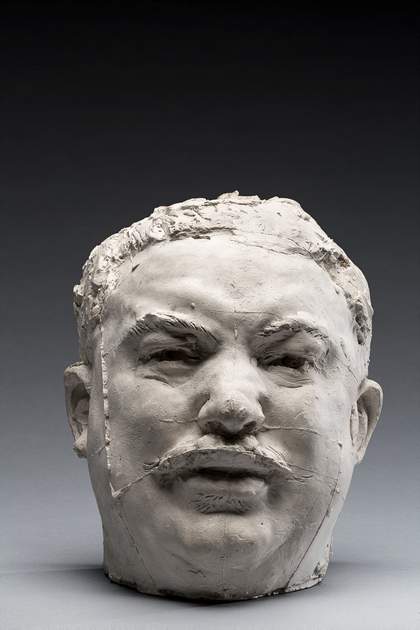

Balzac

This work that has been laughed at, that people have chosen to mock because it could not be destroyed, is the product of my entire life, the turning point of my aesthetics.

Commissioned in 1891 by a writers’ association to make a monument to the French writer Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850), Rodin devoted seven years of trial and exploration to the project. He found a cart driver from Tours, where Balzac was born, to model for the head. For the body, Rodin started with the imposing Study of Nude C, repeatedly adjusting its arms. The final version was adapted from a study of Jean d’Aire, one of the figures in The Burghers of Calais. Rodin replaced its legs and crossed the arms. He then experimented with arranging different types of drapery over this hybrid body. Study for the Dressing Gown, for example, was a plaster cast taken from a real gown.

Unveiled in 1898, the final abstracted figure proved too radical for the commissioners. They refused to recognise the sculpture as a statue of Balzac and rejected it. Though it wasn’t cast in bronze for another 40 years, it is now recognised as a landmark in the history of public sculpture.

Auguste Rodin Balzac, Mask known as the Conductor of Tours 1891 Musée Rodin, S.00610

ROSE BEURET

Rodin met Rose Beuret (1844–1917), a seamstress, in 1864. She was one of his earliest models, soon became his partner, and assisted him in his work for much of his career. In 1866, Beuret gave birth to their only child, Auguste-Eugène Beuret. Despite his numerous affairs, Rodin and Beuret remained together for 53 years. They married in 1917, the last year of both their lives.

Room 3

Movement and Fluidity

Rodin used drawing to study movement and the internal dynamics of the body. Rather than instructing his sitters to strike fixed poses, he would ask them to move freely around the studio.

The works shown here were made in the last decades of Rodin’s life, when he could afford to hire professional sitters. After the 1890s he focused primarily on female figures. The conventional relationship between male artist and female model was starkly unequal, and Rodin did not identify these women, or personalise their nude bodies.

Rodin’s approaches to drawing and sculpture were remarkably similar. He would translate the initial drawing into several copies. Each of these could generate a new work, independent of the original sketch. Just as with his small sculptures, Rodin was in the habit of rotating his drawings, as the written annotations in different orientations show.

Rodin usually began in graphite. He then added watercolour or gouache paint to generate a sense of fluidity, as if the bodies were immersed in mist or water. This process can be compared with the dipping of his sculptures in plaster slip or ‘lait de platre’, a liquid solution of watered down plaster powder, which enveloped the figures, softening their volumes and angles.

Room 4

HÉLÈNE VON NOSTITZ

The German aristocrat, writer and socialite Hélène von Nostitz (1878–1944) was introduced to Rodin in 1900, after visiting his exhibition at the Pavillon de l’Alma. Von Nostitz and Rodin struck up a lasting friendship, eventually leading her family to commission a series of portrait busts, a lucrative sideline to Rodin’s studio work.

Rodin modelled the first of these in 1902. When von Nostitz returned to Paris in 1907, she sat for him again. Several plaster casts were made from the initial clay models. Rodin experimented with these casts, dipping them in plaster slip. The plaster solution filled the facial crevices, softening the figures’ features and allowing Rodin to envision how the work might appear in marble. Trapped air bubbles formed small craters, while uneven layers of slip created wavering lines. Rodin made no attempt to disguise or remove these execution marks. In fact, he added more, carving into the surface of both the wet and dry plaster to emphasise its changing consistency.

Waves of light seemed to envelop the marble. For the first time in my life I was so deeply affected by a piece of sculpture my eyes filled with tears.

Hélène von Nostitz

Auguste Rodin Hanako mask, type E 1907–10 Musée Rodin; S.00194

OHTA HISA (HANAKO)

Born in Japan, the actor and dancer Ohta Hisa (1868–1945) performed under the name Hanako, meaning ‘Little Flower’. She was 33 and still relatively unknown when she came to Europe to perform. Inevitably, these performances reflected a Western idea of Japan. Her fame was based on her compelling enactment of seppuku or harakiri, a Japanese suicide ritual traditionally reserved for men.

Ohta and Rodin met in 1906, when she performed at the Colonial Exhibition in Marseille, an event held to bolster support for France’s colonial conquests. Rodin was fascinated by her stage persona. After early realistic portraits, he tried to capture the look of anguish she displayed on stage, an expression so tense that she could not hold it for longer than half an hour.

The Musée Rodin holds over 50 busts and masks of Ohta, more than any other sitter. While in most of his sculptures Rodin focused on the body, he only depicted Ohta’s face, an allusion perhaps to the masks used in Japanese theatre. It was not until Rodin’s death that Ohta finally received the two masks he had promised her in return for her labour.

It was impossible to hold this look for such a long time. I couldn’t help moving a little bit, and M. Rodin said, ‘Not so much Hanako, not so much’.

Ohta Hisa

Room 5

Camille Claudel

Camille Claudel was born in 1864. Like many women artists, she faced discrimination. In nineteenth-century France, women were not accepted into the official art school, the École des Beaux-Arts, and were similarly excluded from official commissions and competitions. Claudel enrolled at the private Académie Colarossi in 1881.

Impressed by the quality of Claudel’s work, Rodin offered her a job as a studio assistant. They soon became confidantes and ultimately lovers. Claudel and Rodin influenced and supported each other’s work. However, the power in the relationship lay securely with Rodin. He was her employer, a celebrated artist, and did not want to break with his long-term partner Rose Beuret. Eventually, in 1892, Claudel ended their relationship.

She continued to work and exhibit to critical acclaim until 1905, while increasingly experiencing problems with mental health. In 1913, at her family’s request, Claudel was admitted to the Ville-Evrard psychiatric hospital. She died in Montdevergues hospital on 19th October 1943 at the age of 79.

Prior to his death, Rodin approved plans for a dedicated display of Claudel’s work in the museum he left to the French State.

If there was still time to change professions, I would prefer that.

Camille Claudel

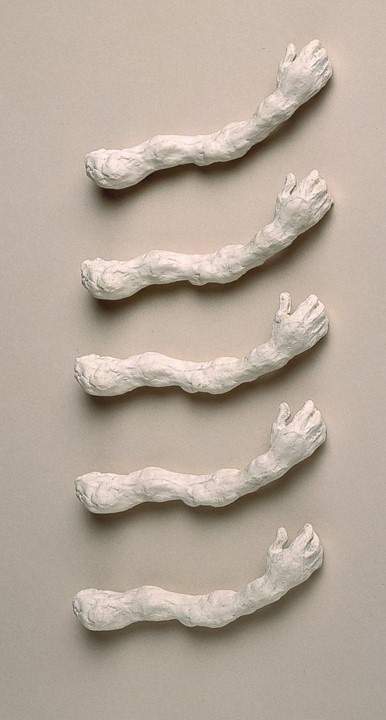

Auguste Rodin Abattis, right arms 1890-1900 Musée Rodin, S.4650 to S04654

Auguste Rodin Monument des Bourgeois de Calais 1889 Musée Rodin, S.00153

Giblets

During the making of The Gates of Hell Rodin built up a collection of individually modelled heads, arms and legs. Small hands, especially, filled drawer after drawer in his studio. Rodin liked to call them ‘abattis’ (giblets).

Multiple plaster casts were produced of each limb. Rodin reworked these casts, experimenting with their proportions and orientation. Sometimes they broke, and these accidents could inspire further alterations, such as putting the parts together in changing configurations. The abattis never belonged to just one figure but represented a stockpile of parts to draw upon.

Hands also frequently featured in the photographs that Rodin commissioned of his sculptures. He probably never used a camera himself, but worked closely with professional photographers including Eugène Druet, Edward Steichen, Stephen Haweis and Henry Coles. Often, these images helped him to reimagine his works through isolating specific gestures or considering bodies from unexpected angles.

Rodin exhibited photographs alongside his sculptures for the first time in 1896, at the Musée Rath in Geneva. The photographs shown here were among those included in his retrospective at the Pavillon de l’Alma.

Room 6

The Burghers of Calais

In 1346–7, the French port of Calais was besieged by King Edward III of England. He agreed to spare the townspeople if six of their leaders surrendered to him with ropes around their necks, ready to be executed. Eustache de Saint-Pierre and five fellow citizens volunteered for the task. They were ultimately spared.

In 1885, Rodin was asked to create a monument to Eustache de Saint-Pierre. Rather than follow the custom of celebrating a single heroic figure, he decided to depict the collective sacrifice of the group. The burghers were first modelled unclothed. Fabric tunics were dipped in plaster and draped over the nude sculptures. This allowed the withered outline of the bodies to be seen clearly beneath the garments. Rodin exaggerated the size of their bare, bruised feet, emphasising the men’s vulnerability and hopelessness as they walked towards their death.

Initially Rodin planned to install the sculpture high up, to be viewed against the sky. He then changed his mind and took the burghers off their pedestal. By placing them on the same level as the viewer, showing their common humanity rather than elevating them out of reach, he revolutionised monumental sculpture.

A bronze cast of The Burghers – on a plinth – stands in Victoria Tower Gardens, next to the Houses of Parliament in Westminster

Auguste Rodin The Three Shades before 1886 Musée Rodin, S.03970

Room 7

Fragmentation and Repetition

Rodin was fascinated by the fragmentary state of ancient Greek and Roman statues in collections such as the British Museum. Some of these works had been damaged by the ravages of time. Others were broken when they were forcibly removed from their original setting. For Rodin, the damaged state of ancient statues seemed to heighten their expressive power. He began to experiment with removing parts from his own works.

The Inner Voice was initially part of a group of three figures Rodin conceived for a monument to the French writer Victor Hugo. The knee was first broken off to fit the sculpture into the monument. Eventually the figure was enlarged and presented on its own. However, Rodin kept the knee truncated, embracing its removal as part of the object’s history.

Another innovative strategy was to use multiple casts of the same figure. Three Faunesses consists of an identical female figure repeated three times. A single male, previously representing Adam, was similarly reproduced to become The Three Shades. Rodin’s decision to present duplicates of a single form within the same group was a radical departure from the historical emphasis on sculptures as unique objects.

Assemblage and Multiplication

Early in his career, Rodin worked in a number of decorative art studios, producing objects for serial production. He learnt how to get the most out of a single model, casting multiple copies and reworking each one.

He applied these lessons to his own studio work. He dismantled and reassembled existing sculptures in endless combinations. By casting different parts of figures separately, he could alter the overall composition without having to remake the whole sculpture. Each fragment could exist both individually and as part of a greater whole. The Head of a Slavic Woman, for example, found its way into many other sculptures, taking on new meaning and significance each time it was used.

The same figure could be repurposed in different orientations. Arched Female Nude was flipped and rotated into various positions by Rodin. With each turn, the physicality of the body was altered, from propelling forward to falling downwards.

Appropriation

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw a booming trade in antiquities. One reason was the sharp expansion of European colonisation. This led to a stream of artworks, many of them stolen, being sent to Europe.

Rodin was himself an avid collector of ancient artefacts from Greece, Rome, Egypt, Japan and China. Between about 1893 and 1917 he amassed over 6000 pieces, including Boeotian and Etruscan cups, Roman amphorae and Naqada vases. These works were purchased primarily from Parisian antique dealers and housed in a specially designed building at his home and studio in Meudon, outside Paris.

Around 1895 Rodin began to appropriate some of the terracotta vessels in his collection. He added small plaster figures, which the poet Rainer Maria Rilke described as ‘floral souls’.

Rodin’s use of existing objects prefigures modernist strategies such as cubist collages, readymades and surrealist objects. Yet in the process of creating his own work, he was effectively destroying the ancient artefact.

Room 8

Rodin in the Twentieth Century

The 1900 exhibition turned Rodin into an international star. Its triumph, to no small measure, was thanks to Rodin’s staging. Instead of a formal display, it evoked a studio visit. Instead of a workshop with multiple production teams, it mythologised the idea of the solitary genius. Instead of the many intermittent stages involved in making sculpture, it emphasised the ‘artist’s touch’ as the hallmark of creative authenticity. Its celebration of experiment, rule-breaking, and unconventional materials and techniques lastingly expanded the field of sculpture.

Rodin did not rest on his success. He kept revisiting existing works to invent new ones of extraordinary vitality. From being caught in the clutches of death, The Son of Ugolino, for instance, turned airborne, the very image of life and movement. Equally, the fragmented torsos of The Punishment and Triton and Nereid became powerful works in their own right. Rodin grew especially fond of the undulating surfaces created by enlargement. Visible seams and joints invited the viewer to retrace the process of making, as did the gouges and nail marks Rodin deliberately left as traces of his hands.

Rodin initially took refuge from the First World War in England and Italy. In 1916 he suffered a stroke at his home in Meudon and died the following year. Together with Rose Beuret, he was buried in their garden, next to the re-erected Pavillon de l’Alma. Their grave is marked by a bronze cast of The Thinker.

Audio Guide

Rodin challenged structures and norms through his experimental approach to making. How do artists continue to disrupt ways of working today? What can we learn from looking at Rodin through the lens of contemporary artists, makers and activists?

Hear Phyllida Barlow, Dan Daw, Grace Nicol, Giovanna Petrocchi, Thomas J Price and Jala Wahid speak about Rodin, making and working as artists today.

Meet the artists

Phyllida Barlow

Phyllida Barlow is an artist working with sculpture and drawing. She uses a variety of materials to interrogate and disrupt sculptural conventions.

Grace Nicol

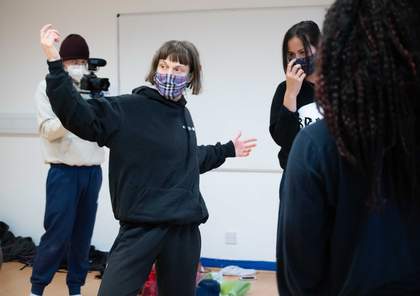

Grace Nicol is a choreographer, curator and activist. Her practice focuses on object-body relations and materiality, to explore movement within social and political contexts.

Phyllida Barlow in her Studio, 2018

© Phyllida Barlow

Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Cat Garcia

Grace Nicol Slip Mould Slippery, Grace Nicol and Sinead O’Dwyer

Image by Ottilie Landmark

Dan Daw

Dan Daw identifies as a Queer, Crip (disabled) artist and develops work at the intersection of theatre, dance and activism. He is currently The Associate Artistic Director of Candoco Dance Company.

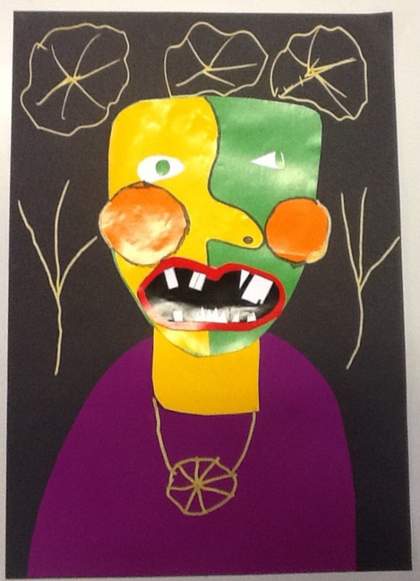

Giovanna Petrocchi

Giovanna Petrocchi is a visual artist. Her practice focuses on the combination of archival imagery, personal photographs, collages and 3D printing.

Dan is pictured with collaborator Christopher Owen

Photo: Hugo Glendinning

Giovanna Petrocchi, Modular Artefacts, Mammoth Remains, 2019

Jala Wahid

Jala Wahid works across sculpture, installation, video and writing. Her practice explores her Kurdish heritage, thinking about Kurdish identity and politics from a diasporic or Western perspective.

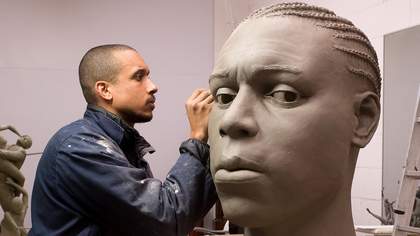

Thomas J Price

Thomas J Price is an artist working across sculpture, film and photography. His practice engages with issues of power, representation, interpretation and perception in society and art.

Jala Wahid, Carved my Soul in Two, 1

TJP working on original clay sculpt in his studio. Thomas J Price.