Indigenous worldviews recognise that all beings are connected and all life is interdependent. Can we relearn to be human, navigating back to this fundamental equation of life?

Máret Ánne Sara

About Máret Ánne Sara

Máret Ánne Sara is a Sámi artist whose work advocates for ecological justice by centring her community’s knowledge and practices. The Sámi people are indigenous to the Sápmi region, which spans northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Kola Peninsula in Russia. Reindeer herding is a cornerstone of Sámi culture, shaping the relationship between people, lands and animals. It recognises the interdependence and intrinsic value of all living beings. Sara honours this worldview in Goavve-Geabbil, inviting us to embrace the power of Sámi philosophy and science.

‘Goavvi’ is a snow condition caused by extreme temperature fluctuations due to climate change. Rain and melted snow freeze into layers of ice on the surface of the land. This prevents animals from accessing the food beneath, leading to widespread malnutrition and starvation of reindeer. ‘Geabbil’ signifies the importance of adaptability and mutual support in the face of this ongoing crisis.

The Nordic colonisation of Sápmi involves centuries of land dispossession, forced assimilation, and suppression of Sámi ways of life. Today, laws and policies continue to threaten Sámi culture, alongside the expansion of mining operations and energy industries. These developments are destroying reindeer grazing lands, disrupting migration routes and encroaching on ancestral calving grounds – which are central to Sámi reindeer herding, holding deep cultural and spiritual significance.

Responding to Tate Modern’s site, a former oil and coal power station, Sara invites us to view energy not as a resource to be exploited, but as a sacred life-force, sustained through reciprocal relationships. This perspective resonates with Sámi science, which encompasses knowledges, practices and values, developed through deep connection and interaction with animals and lands across generations.

GOAVVE-

In Sara’s sculpture Goavve-, reindeer hides are tightly bound by electrical power cables. The cables point to the continued extraction of energy and degradation of lands, waters and ecosystems, not only in Sápmi, but globally. In contrast, the hides embody a different form of power: one grounded in ancestral knowledge and spirit.

Non-verbal communication plays a vital role in Sámi culture. The term ‘váivahuvvon hádja’ describes the scent released by reindeer when they are scared, as a biological warning signal. Sara has imbued the hides in Goavve- with this smell, inviting us to attune ourselves to other forms of perception and communication.

As she explains: ‘We’re all connected, everything communicates, if we’re open to receiving this information… part of our responsibility now is to reawaken that awareness. Relearn to relate to nature again.’

‘Duodji’, the traditional Sámi making practice, merges technical skills with ethics, spirituality, and environmental understanding. Sara makes use of bones and hides in her work, to honour the lives and spirits of the reindeer and give new purpose to parts of the animal not used for food. This custom strives to ensure that nothing is wasted, serving as a gesture of gratitude and respect.

Goavve- stands as a living monument, with Sara calling on us to remember that ‘nature is not an endless resource to exploit. If we expect to receive from it, to sustain life for all beings, we must also ensure its health and ability to regenerate’.

Cross-section of reindeer nasal cavity (Photo © Helen O’Malley, 2025)

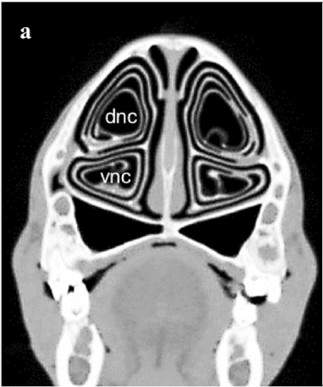

CT scan showing a cross-section of a reindeer's nose (Source: Casado Barroso, 2014)

-GEABBIL

-Geabbil is a maze-like structure. Its shape is based on the internal anatomy of the reindeer nose. Extremely energy-efficient, the nose can heat air by 80°C in a single second, enabling reindeer to survive in cold conditions. Sámi science honours nature’s intelligence, spirit and power. As we move through the structure, Sara invites us to connect with the enduring knowledge and energy that flows through its materials and passages.

The wall carvings are drawn from reindeer earmarks – distinct patterns, passed down through generations of Sámi families to identify the animals. These marks are signs of commitment: a pledge to care for and protect the reindeer and their environment. The structure is permeated by smells drawn from native plants in Sápmi, such as lichen and shoegrass. Sara also includes the smell of reindeer milk and her own breastmilk. Together these smells signal nourishment, renewal and possibility for the future.

A resonant soundscape fills the Turbine Hall. It weaves together recordings from the Sápmi landscape with the Sámi musical practice ‘joik’, which uses voice to evoke the essence of a person, animal or place. At the heart of the structure, we are invited to listen to stories shared by Sámi knowledge keepers. Storytelling plays an important role in Sámi culture, preserving and transmitting knowledge across time.

As Sara explains, ‘these ancient systems are still alive, but fragile and fully dependent upon Indigenous Peoples’ right to live within their lands and ways.’ She calls on us to respect and stand with Indigenous Peoples, upholding their science and philosophy as progressive, powerful and vital to shaping the future of our shared world.

Storytelling

Storytelling plays an important role in sustaining and sharing Sámi knowledge. These audio recordings are composed of extracts from Sara’s conversations with Sámi reindeer herders and knowledge keepers Ellán-Ánte Ánte, Asta Mitkijá Balto, Mari Boine, Máret Rávdná Buljo, Mihkkal Niillas Sara, Nils Oskal, Anne Marie Siri, Ánde Somby and John Andreas Utsi.

Audio clip 1

This conversation reflects on the Sámi philosophy of asking permission from animals, waters, lands, and spirits.

Mari Boine

I grew up by the most beautiful river on Anarjohka which due to colonisation became the border between Norway and Finland. We harvested and gathered from nature. My father and mother fished for salmon. So did the other families around us. Grandmothers, and mothers, and aunts, took us children on countless trips to pick berries. My uncles and brothers hunted, put up snares and went to check the snares each morning. Our summers were full of all kinds of gifts from nature and our elders taught us how to preserve them, to survive the long winters. Their unspoken message was never take more than you need and what nature can tolerate. Leave a place like it was before you arrived.

Asta Mitkijá Balto

Back in 1981, we young ones built a traditional turf hut, with our parents as our guides. We worked horribly and decided it should be 4x4 m2. But then we discovered an ant nest in one of the corners. One of my brothers suggested that we burn it down, so we could continue building the hut there. We said, no, we can’t burn it. So he said, okay, I’ll just kick it down. And he did. That evening, our parents asked how the day had gone. We told them, one of us kicked down the nest. Lord, no — you didn’t! They spoke. Don’t you remember anything we’ve tried to teach you? Why?” We asked. “What’s the problem? That’s their home, they said. They’ve arranged everything there, and now you’ve destroyed it. That’s not good in the slightest. And the ants — they understand what you have done. Just wait and see what happens.

Weeks later, my sister moved into the hut and lived a very authentic Sámi life for two weeks — until the ants began to enter. They came from every direction, completely overtaking the hut. She had to resort to traditional tonics and remedies. Our parents said, that was their response. You didn’t even speak to them. If you had just asked for permission to move them, if you had shown any understanding… but you didn’t.” And then, the following summer, the ants made their way to our parents’ house — a full kilometre away from the hut we built. They entered it too. Our parents just nodded. That’s how it is, they said.

Mihkkal Niillas Sara

Asking for permission is often done when you are in places where you don’t usually stay. For example, if you want to set up a lávvu in a certain spot, you ask for permission to be there so you can rest peacefully. If you haven’t asked for permission, you might find your sleep disturbed.

Nils Oskal

Asking for permission, it might seem a bit funny. If you do ask, how do you get an answer? I don’t think this should be exoticised too much. It has an existential point. It’s about cultivating openness and humility. It’s about learning that you are not alone in this world, and recognising your own role within it. This is a worldview.

Asta Mitkijá Balto

We ask for permission to make a fire when we’re out in the forest, and ask again before setting up camp. And when we’re ready to leave, we look back to see whether we’ve disturbed anything. This practice is important especially for children to learn. We teach them to leave things the way they were. In some Sámi kindergartens, even though teachers have not always dared to teach these aspects of our spiritual heritage, children still say something like; “We can’t leave the bonfire stones like this — we have to put them back as they were.”

That’s exactly the point: we leave the place as we found it. It’s a form of respect — not just for the land, but also for the ancestors who came before us, who handed down these lands and knew how to keep them alive. It’s also about the stories embedded in the landscape. Instead of just saying, like in a textbook, “Teach children to respect nature and avoid destroying it,” we practice it. We arrive in a place and ask: “Do we have permission to be here, with this fire?” If it won’t light, we consider — maybe we’re not meant to be here. Maybe we’re disturbing something. And we should move on.

When the Sámi University was being built in Kautokeino in 2009, the principal, Mai Britt Utsi, wanted to honour this old tradition. She had all the builders, technicians and engineers who came from the state, stay overnight at the building site, to feel and try to sense whether they were welcome to dig into that ground. Of course, the project had to follow regulations and formal procedures that were set. But why did she do it? Because the act of asking for permission is rooted in deep philosophy. And that simple act remains a powerful symbol — with an important pedagogical role. It teaches us to ask before we take.

Mihkkal Niillas Sara

The question is: Who or what you are asking permission from? From the land itself? In Sámi thinking, there are also spirits — beings that cannot be seen. The idea is that another realm exists. We don’t know in what shape or name but there is something in our surroundings. There are stories of things seen and heard that are not here, serving as confirmation of this second realm. When you communicate with your surroundings, you acknowledge these spirits by not taking without asking. It is important always to communicate and come to an agreement with your surroundings when traveling, so that your journey may end well.

Mari Boine

Foreign priests and missionaries had for hundreds of years, built churches in Sápmi, worked to purge it of what they called paganism. Banned and burned our drums, punished our spiritual leaders, the noaidi’s. Filled our people with self-hate and shame and convinced them their animistic outlook on life, their reverence for mother nature was devil worship.

I also grew up with a view of a sacred mountain, Áilegas. With a sacred spring in the neighbourhood, Suttesaja. But this, I didn’t know then. These were never mentioned or talked about, neither at school nor at home. Nor was it ever mentioned that we used to ask permission from nature before we cut down a tree or branch. What I grew up with was stories from the bible, saying that man should rule over nature, and that man should rule over woman. No story saying that the animals and everything in nature were our relatives and should be treated with respect. I later learned that the joik, our traditional singing, is a way of remembering. The knowledge was passed on through joik from one generation to the other. Every child was given a joik and welcomed to life and society by a joik. When we do our joiking we don’t sing about, we sing into being a person, a landscape, an animal or a situation.

Máret Ánne Sara

I as a Sámi, come from an oral culture where knowledge and information are passed through stories, rituals and customs, through which a much larger knowledge system and philosophy emerge. Sámi stories can be fine entertainment, but they also contain deep layers of meaning that often remain hidden for years before they begin to make sense in relation to other knowledge gained and embodied.

My grandfather used to tell me a story when I was a child. It was a fearan, a type of Sámi story telling technique that aims to retell an event that someone has experienced in real life. This fearan was about an old lady that lived by the coast region, of where my grandfather moved with his reindeer in his youth and young adulthood. The old lady lived in a small farm with a few cows. Every evening, she would tie her cows in the barn to ensure that they stayed calm and secure until the morning. One summer, she was getting very frustrated because she would tie her cows in the barn in the evening, but when she came to let them out in the morning, one of the cows was always loose inside the barn. She was getting more and more frustrated and didn't know what to do about it. Then one night, another old lady, an ulda from the underworld, came to visit her in her dreams. She turned out to be equally annoyed, and told her to move that cow because it was peeing right onto her kitchen table, and then she left. When the old lady woke up, she remembered this dream and decided to move the one cow that was always loose in the barn. After that, the problem stopped.

As a child I remember this as an exciting and mysterious story, but as I grew older, I started to see the depth of it. Of how eloquently it, by the use of the fearan format, vividly retold by storytelling masters, enabled me to live or re live the event and almost bodily experience the story through my own sensory imagination. It was a way for me to embody an understanding of close proximity and interconnectedness between different realms, spirits and nature that we share with so many other life forms. And whether I choose to believe in different realms, in ulddat, the underworld people or in spirits, the story nevertheless instils a deep awareness of the fact that all of my presence and being, potentially has an impact on other life around me, seen or unseen. Thereby, training from a very young age to consider consequences of one’s actions in a much larger perspective than what my eyes or consciousness immediately spans.

Nils Oskal

What is the relationship between experience and articulated understanding?

Experience has the power to reveal something previously unknown or unrecognised. It plays a fundamentally different role in the process of understanding than articulated knowledge does. When I experience something, it can transform how I see things—even things I thought I already understood. It also allows me to clarify and solidify my understanding of things.

Ánde Somby

I used to pose a question to my students. I’d say, “Here, I’m teaching, and there’s a mosquito on the window. I’m holding tweezers in my hand. Now, imagine I pluck off one of the mosquito’s legs — is that okay?” The point of the exercise is that there’s no law against it. Legally, no one could punish me. But the real question is: is it ethically right? I like to ask students whether a mosquito has any integrity, or value that makes it wrong to harm it. Is there something sacred in a mosquito? This often sparks an interesting discussion. Students typically split into two groups. One group says, of course you can — it’s not illegal. The other argues, no, you can't — you must have a reason, a purpose to cause harm. If you’re studying mosquitoes, maybe. But not just because. And that’s where the ethical conversation begins.

Asta Mitkijá Balto

Storytelling is a very Indigenous way of sharing knowledge. If we can say that we have a theoretical basis for what we do and how we understand the world, then stories are a rich source of information, of knowledge, experiences and wisdom. They teach us how to live —and how not to live. There are so many kinds of stories. Of course, some are just for enjoyment, to make us laugh and share good moments. But many carry important lessons, offering guidance to children, young people, and adults alike — especially about values that matter deeply to us Sámi. You see, storytelling reaches people a little differently, than simply telling them directly what they should or shouldn’t do. Storytelling has a deeper impact, it helps people to understand why something matters.

Audio clip 2

This conversation explores the Sámi agreement of living in partnership with reindeer. (Content Warning: It includes a description of animal slaughter.)

Máret Rávdná Buljo

I was only one year old when my mother and father gave me my own reindeer mark derived from the marks on my father’s side of the family. They put that mark on the reindeer calves that were mine. I learned to put on the mark with a blessing, saying the words and making a cross so that good fortune — reindeer-luck — would follow you, follow me and my duty. The mark is on the reindeer’s ear, here, so that one can see who the reindeer’s caretaker is and whose hands it has been entrusted to. It is the responsibility of the owner of the mark to take care of the reindeer bearing their mark. It’s like a contract between people and reindeer according to the ancient Sámi tales. The reindeer has promised the Sámi meat, hide and antlers, and in return the Sámi herd the reindeer so that they can graze and live in safety.

Máret Ánne Sara

You must remember to bless the animal before the stab, my grandfather says. It is a heart stab, and we call this act of killing, giehtadit. Giehta means hand, and giehtadit, means to release it from your hands or your entrusted care. I’m about ten years old at the time. I see the reindeer's eyes widen as the knife hits its heart. It looks painful, and I have to turn away. I can’t watch — I never could — but grandfather remains completely calm. He sits beside the reindeer and strokes it gently until it stops moving.

But why giehtadit? It looks painful. I’ve seen how they do it in the modern slaughterhouses. While our way of killing has been banned, the way in which Norwegian law prefers and enforces the killing of reindeer, is by a bolt gun to the forehead. The reindeer collapses instantly, as if its legs have disappeared beneath it. It looks so fast, so effective. But it doesn’t die from that shot, my dad explains. It’s only paralysed—then hoisted by one leg onto an assembly line and sent to the next station. There, it’s stabbed in the throat, and the blood gushes onto the floor. In principle, it’s the same act of killing, only the reindeer bleeds to death outside its body, down the drain, before its head is cut off and tossed into a waste bin. That bolt gunshot, you know, has to be precise. If it’s even slightly off-center, the reindeer might vomit up its stomach contents through its nose, which makes the whole head inedible. So the butchers discard all heads, just in case.

“It’s so we can use the blood,” someone else explains to me on a later occasion, about the heart stab, giehtadit. The idea is to let the heart pump the blood out of the muscles and collect it in the chest. This way, the meat contains less blood and doesn’t sour as quickly—which is important when drying or preserving it without a nearby freezer. And that blood, not a drop is wasted. Dad chops off the forehead from the dead reindeer's head and marks a symbol with the tip of his knife against the back of the forehead bone.

“What was that?” I ask. “That’s just how we do it,” he says simply. He doesn’t say much more, but I understand—that it’s a blessing, to the animal’s soul and spirit. An act of gratitude for the life it’s given us. In that moment, it feels as if a new life begins with the body that remains. The soul has moved on, and now the body is full of potential and purpose. It embarks on a new journey through our hands, guided by our knowledge, traditions, and love. That journey involves a lot of hard work — but also endless possibilities. Food, in all forms and flavours. Sustenance, clothing, tools, duodji — or, God forbid, art.

That’s how I’ve learned it. Logic and values. Ethics and morality from our own point of view. Understanding, through practicing rather than preaching, why we do things the way we do. Even though it takes a strong heart to Giehtadit, the holistic practice embodies deep ethics. While life is surrendered for the survival of the community, you act from a sense of deep respect and gratitude, where you take only what you need, and use everything you take. It all comes from the knowledge held in the hands: how to treat the animal — alive, dead, and during the transition in between with respect and appreciation. Hides, bones, and everything else. I use this knowledge often in my art. And every time I do, I’m brought back to my grandfather — who is no longer here. To my father — who is probably in the mountains. To my grandmother, also past — but who taught me every stitch for every kind of hide or intestine, for every intended purpose. She taught me about barking and scraping hides, about leather’s flexibility and fragility, and so much more. They are all with me when I sit down to work, even now that I create for an international art world, rather than the cold days of the Sámi winter night.

Ánde Somby

The ancient agreement between human and reindeer is something I grew up with. The reindeer says to us: "I know I carry all this meat. But the wolf tears me apart so violently that I live in constant fear. When the time comes for me to die, I ask for two things. First — make sure I don’t have to be afraid. Let me die in peace. Second — once I’ve given my life, use everything. Every part of me — my antlers, bones, intestines, sinews, skin—everything should be put to use."

That is the ancient contract. From the reindeer’s side, it offers its body — its meat. From the human side, the contract demands a peaceful death, and full respect and gratitude through the complete use of the body. And every time you work with sinew or bone, you’re fulfilling that contract. It also means eating all the meat. Those of us raised in the traditional way know: every bone should be rinsed clean. My grandmother used to say that each bone should look like the last year’s bone — completely clean, with no meat left on it. That’s the system. That’s traditional eating. It’s about respect and responsibility.

Nils Oskal

Humans and dogs have a contract. We must treat dogs only in ways that they would voluntarily agree to. The concept of a contract is very important in philosophy — especially in English moral and political philosophy. There, the concept of the contract is central. And yet, we have our own version of that contract...with the dog. It’s kind of funny when you think about it.

Mihkkal Niillas Sara

The agreement between the reindeer and the Sámi, also reminds me of an ancient story about a pact between the dog and the Sámi. According to the story, when the Sámi needed help, they approached various animals — the bear, the wolf — but their demands were too high. Only the dog made a reasonable offer: to provide support in exchange for food. The dog also asked for its life to be ended when it grew too old to care for itself. At its heart, it’s a story about a partnership, a mutual agreement between humans and the dog. The story of the pact between the reindeer and the Sámi sounds similar to this.

The reindeer is a close animal to the Sámi. Both sides make a promise regarding their responsibilities.

The well-known story of Háhčešeatni and Njávešatni is about two different types of caretakers: Njávešatni is a gentle, attentive guardian who takes good care of her reindeer. Háhčešeatni, by contrast, is careless, brutal and neglectful. The reindeer talk amongst themselves. The reindeer in Háhčešeatni's care want to run away and become wild caribou, while the reindeer in Njávešatni’s care want to stay, feeling safe and well cared for. Háhčešeatni’s reindeer eventually escapes into the wild. Furious, she throws the empty reins left behind by the reindeer, they get tangled in the branches of a nearby tree. When she pulls back the reins, the branches gather into clusters — today these nest-like clusters, normally in birch trees, are a sign of illness. In Sámi, they’re called Háhčešeatni lavžegihppu — “the reins of Háhčešeatni”, in reference to this story.

In Sámi philosophy, nature is a carrier of memory and ethics, trees themselves become existential reminders of how our behaviour affects our surroundings. This story serves as an ethical reminder to care for the reindeer, and think deeply about their well-being.

Nils Oskal

As children, we grew up with these stories — Háhčeseatni and Njávesšatni — especially in terms of reindeer husbandry. Háhčeatni’s reins are part of that world. You see them in the trees, and you remember. We didn’t just listen to these stories — we absorbed them on an existential level. When you come across a tree with a certain kind of branch, you might find yourself thinking: How did Háhčeseatni struggle here? These stories were used to teach us right from wrong — to learn how a human, a reindeer Sámi should live and be.

Máret Ánne Sara

I titled one of my recent artworks “Háhtešeatni doali dádjadit.”. My mum was skeptical and asked “Why do you refer to Háhtešeatni? She’s the bad one — what do you meant, are you implying that we are such?” I told her no, I don’t mean that we, the Sámi, are bad. What I mean is that we, as the rest of the modern world's population, are caught on Háhčešeatnis kind of path, and we all have to find a way to navigate it. I think we need to open our eyes and look very deep into ourselves... If you examine Háhtešeatni more closely, she represents a kind of extractive logic—one that doesn’t care about ethics or consequences, that doesn’t distinguish between what is good or bad. It’s very much like the mindset driving today’s Western capitalist systems—the dominant logic in much of the world. But our original thinking is quite different.

The values of Njávešatni, Háhtešeatni’s counterpart, are the values we are encouraged to strive for. In this context, I’ve been studying Sámi philosophy — what it is and what it teaches. Two of its central principles are care and responsibility: that implies how we think and how we act. For example, to take only what is needed, and from what we take, we have the responsibility to use all. You shouldn’t destroy or leave a harmful trail behind you. You should leave things in order and in good health with a consciousness of several generations. And remember that we are all connected. It’s about how our own behaviour mirrors our role and responsibility as one living species in a network of so many. Nature and animals, nature and humans, we cannot separate them. So, we have to learn to live in respect and dialogue with all life forms. Our responsibility is to strive for the balance and health of our surroundings, because that is the foundation of all life. I guess my work points to our responsibility, to re-remember this.

Mihkkal Niillas Sara

The main point is that the reindeer needs a good reason to remain a reindeer — and not become a caribou. That reason lies in the agreement with humans. I sometimes say that the siida—the community of relatives living together with their reindeer—is a partnership between humans and reindeer, where both have a voice. It’s a compromise. Within this siida compromise, the dog also plays a role. People have made agreements with both the reindeer and the dog to form a functioning community. Each is an active participant in that agreement, and each has influence.

Máret Rávdná Buljo

Good treatment of the reindeer gives reindeer-luck, which we call boazolihkku. And boazolihkku is a word that we were taught to pay attention to. Already as children we did what we could to bring reindeer-luck. After eating a meal, we would gather up all the bones and take them outside and give thanks for them. We also learned the words to say before throwing away the bones so that new reindeer would come forth from them.

One shouldn’t take the antlers of a live reindeer into a hut or a house. It says that that’s superstition. It’s also an ancient way of honouring the reindeer. Instead, you should hang antlers up on a tree so that the dogs don’t chew on them. Sometimes one would hear about someone with terrific reindeer-luck, whose reindeer grow like trees. That’s because being hung up on a tree is a fitting offering for antlers, because a tree puts roots in the earth and spreads. I have also heard this. It gives also reindeer-luck when the herding dog that helps with the reindeer is happy. The dog needs food, good shelter and to be treated nicely. The dog depends on your hand to take care of it and feed it. Your transport reindeer is also one who depends on your hand and put on a leash. In the morning, even before you have eaten breakfast, you have to check on those reindeer and go to get them loose if they are stuck. It puts animals first. It’s a duty, there is a person in charge. The person’s job is to take care of and provide for those who depends on your hand. Those can be a dog, a working reindeer, a reindeer pulling a sled, a calf, children, sick people, old people. There is also reindeer-luck in thoughts, even luck in oneself.

Using the whole reindeer is a promise from people to reindeer. The skin is used as a rug or clothing, and decorations made with it honour the reindeer. If a strand of fur is floating in your coffee, you could say: ‘Now it will bring me luck.’ The use of bones and antlers in crafts and the eating of meat and guts is done to honour the reindeer. This, too, brings reindeer-luck. When we wear decorations made of parts from reindeer, that is a joy and a feeling of real love. In the old times when people went to where the herd was resting to chew cud, they would dress up, not wear torn clothing. One should also dress up to mark calves, and when one butchers reindeer. That doesn’t mean wearing gold, but just being clean and putting on nice clothes.

Máret Ánne Sara

Nature, animals, humans. From the Sámi perspective and way of life, both physically and philosophically, you can't separate these. I tell my stories through the reindeer because what happens to the reindeer also happens to us. From an Indigenous perspective, I don’t see humans as superior or central. As human beings on this earth, we are simply a part of an interconnection of life forms and the constant dialogue and interdependence between these.

As Gregory Cajete explains it; Practicing Indigenous science and philosophy means opening yourself fully to the natural world — with body, mind, and spirit. The goal is not to objectify or explain the universe, but to understand and honour the responsibilities and relationships humans have with the world — relationships that carry a duty to care for, sustain, and respect the rights of other living beings, as well as the plants, animals, and places we inhabit. Only by doing so, Cajete says can we ensure our own health and life.

Audio clip 3

The conversation examines the Sámi philosophy of living in participation with nature, and the transmission of knowledge across generations.

Máret Rávdná Buljo

“Child, lay your ear against the earth and listen. Close your eyes and listen to the sounds of the earth, there’s a heart throbbing, do you hear it?” This is how I learned to listen to the earth’s sounds. Travelling with the herd in spring migration, I listened. And for real, the earth had a different sound from one place to another. My ears started to hear the sounds. There were sounds in the snow, there were sounds in the trees, and other sounds under the water. In winter, in the polar night, I would sit outside alone for a long time and try to hear the sound of the Northern Lights. And really, it made a sound! But not all over the sky – it had to be special. Cold and blank. I learned to be there, I learned to be still and commune with nature. I learned to sit beside the flock and to herd, to listen to the sounds of the herd when they are digging in the snow: the bells that tinkle, the antlers that rattle, the grunts and snorts. The reindeer hooves that crunch, the sound of chewing cud through the still air when they settle down to rest. These sounds filled my ears and my core, becoming my home.

A little calf falls to the ground when it is born from the warm and safe belly of a reindeer mother. In the beginning its legs won’t carry it, it can barely lift its head. The reindeer mother quickly licks the calf dry. It is a tough world it comes into. It can be chilly and there can be wind, rain or a snowstorm in the spring when calves are born. Predators are also on the watch. The first refuge for the calf is the earth. Its first place in this world. Its head against the calving ground and its little ear that is learning to listen to the sound of the earth. It hears the sound of the wind, of streams flowing, of snow melting, and the sounds of birds that have come north.

By its mother’s side it learns to migrate when it gets a little bigger, learns to listen to the sounds of the places and the throbbing of the earth from one place to another. That way it learns, as all the others in the herd have learned, to recognise the places and where they go on migration. Those lands are their sounds, too, are its refuge, as they are and have been for all the others in the herd through the ages, thousands of ages even.

Mari Boine

Science often confirms what many Indigenous people have been saying in songs, in stories, in their worldview, for thousands of years. Now of course it seems self-evident that rhythm is central to life, our hearts beat, trees pulse, the tides pull, the sun rises, but why was it that so many educated sophisticated men, some of them scientists, sought to silence a simple rhythm instrument. This drum, a circle of wood and skin that speaks to life, speaks of life to life.

The shamanistic beat is very close to our heartbeat, it is soothing, it can take us on a journey and connect us to the non-rational, non-linear and spiritual. This beat is one of the most beautiful gifts I have found. It has been a crucial part of my music ever since. The more knowledge I as an adult gained about my own culture and heritage, the more this question came up. Why was it important to silence our heritage. To make it disappear. The more I travelled around the world and become acquainted with other cultures, the more I realised that this had not only happened in Sápmi, but that this has happened all over the world. To my great joy I eventually discovered that we are not only a small different group in Northern Europe, we belong to a family of 370 million Indigenous Peoples worldwide. People who have inherited myths, stories, songs, rituals, strategies of survival and life wisdom from those who were here before us and who lived close to their earth and land.

Máret Ánne Sara

If we agree that science is a pursuit of knowledge or a way of understanding the world, we can agree that people have done this throughout time. Gregory Cajete points out that while Western science starts with a detached “objective” view where nature is studied as an object which is detached from the human studying it, then on the contrary Indigenous science is born out of lived and direct participation with the natural world. In its core experience, native science is based on the perception gained from using the entire body of our senses in direct participation with the natural world, emphasising our role as one of nature's members.

While Western science accumulates knowledge in the pursuit of control, Indigenous science’s ultimate aim is not to explain an objectified universe, but rather to understand the web of interconnected relationships which form it, in order to better support all life on earth. Cajete describes Native science as a process of discovery or ‘coming to know’, by ‘participating with’ the natural flows of the environment, where knowledge is gained through listening, looking and play. While elders provide guidance and facilitate learning, often through storytelling and rituals, it is the individual’s responsibility to embody the knowledge offered to them.

The chaos theory, derived from the cutting edge of Western science, shows us that systems are unpredictable and largely beyond our control — except in the smallest, most surface-level ways. Nature, in this view, is a complex, ever-changing, and inherently chaotic system. Native science sees the same reality, but from a different angle. It understands chaos — and the creativity that springs from it — as one of the universe’s driving forces.

JOIK Anders Aslaksen Siri recording

Anne Marie Siri

My father Fimben Áillu Ánte, was recorded in 1965, joiking the mosquito. I have used this joik and the poetic lyrics of it in a curriculum book that I am currently writing. I use it as an example of how much knowledge is embedded in seemingly trivial things, like a seemingly entertaining or funny joik. The lyrics are as follows: “The mosquito girl who made the reindeer run, she was the reindeer herder’s helper. How that mosquito girl was chasing them off while the wind boy was steering their direction. The mountain snow patches darkened when the mosquito girl had hummed a few weeks more”.

The lyrics of Čuoikka luohti, the mosquito joik, tell us that the mosquito has great value. It is praised as “the helper of all Sámi”. The reindeer herders know that when the mosquito and other insects arrive, the reindeer start running to avoid them. In this way, the insects cause the animals to gather... This was especially true for the reindeer which had summer pastures on the mainland. The phrase “the wind boy steered the direction” reflects the herders’ knowledge that reindeer instinctively move into the wind — for example, northwards if the north wind is blowing. The reindeer Sámi also know that the reindeer seek out high ground where there are persistent snow patches even through summer, because there it is cooler, windier and less insects. The reindeer like to lie and stand on the snow when the weather is hot — that's why “the mountain snowpatches darkened”. The joik shows that when a person pays attention to their surroundings, for instance nature and wind, they can understand where the reindeer will gather, and where they should go to herd them. Their accumulated knowledge about nature, animals and climate is attuned with a constant analysis of any changes in their surroundings. They activate a different knowledge system and a different way of being and thinking. Becoming almost one.

Asta Mitkijá Balto

Jávredikšun — a simple Sámi term — contains an entire eco-philosophy. In English, we might translate it as “lake-care,” though that doesn’t fully capture the depth of the Sámi concept. Roughly, it means that the lake does not survive on its own; it needs someone to care for it, and in return, the lake gives back what it can. In this sense, the lake is a subject. I think this is a great example of how language reflects philosophy. We humans are not alone in this world, and we do not rule over nature or other life forms. Therefore, we should approach nature with humility and maintain communication with all living things. Mari Boine sings that “The earth is our mother if we kill her, we kill ourselves”. It’s a simple yet profound truth. It connects us to nature in a completely different way. Nature is a subject just as we are subjects. It is not simply a resource to be exploited for our own benefit. This philosophy stands far from the rush to take as much as possible, to become rich, and to spend recklessly. We shouldn’t live that way. That would be a question of morality of life ethics—in Sámi, ollmmožin eallit. Ollmmožin eallit is to live as a responsible human.

Máret Rávdná Buljo

The Sámi language is connected to our lands, work, animals and everything that has a spirit. It is what gathers our life together. It has always been as if nature understood our language in our regions. Spiritually communed with our regions and the life here. In the Sámi lands there are many different dialects and there are also many different designs for clothes. It is as if they were formed from the sounds and appearance of the grazing grounds. The colours in our clothing also belong to our regions, and it is as if the reindeer feels safe when it sees Sámi clothes: happy and filled with comfort. The mountains, too, know our Sámi outfits, coats, bands and the soles of our shoes. From ancient times to today we also change our clothes if we settle in a new place with reindeer. So that the land will recognise its own clothes and language.

Asta Mitkijá Balto

How can we practice listening? Listen with your fingertips — feel the sensitivity. Test your emotional capacity and communicate with your environment: with people, animals, sounds, smells, and so on. Can we regain some of the sensitivity we once had before urban life took over? When we relied on all our senses — seeing, hearing, feeling, smelling, tasting. This, to me, is deeply important: the development of consciousness and using our human abilities to their fullest. I learnt from your work Máret Ánne with smells Du-ššan-ahttanu-ššan The Sami Pavilion Venice Biennale 2022. What is smell? Can people sense fear from scent?

Máret Ánne Sara

I have a strong childhood memory from growing up in a reindeer-herding family in Fala. Fala is our calving area, summer pasture to our reindeer. It’s an island in north of Norway which over time has become a heavily industrialised community that includes the gas field Snøhvit, the Nussir copper mining project and also massive powerlines to sustain the heavy industries. Hammerfest, with its rapid industrial expansions and also a lot of racism towards the reindeer Sámi, has been a tense and difficult area to return to in summers. As a child I sensed this discomfort, even if I was partly shielded from it. Up on the mountains though, I felt safe. My father’s knowledge of nature, animals and the improvisational skills that come with nomadic life made me feel at home and very safe. In reindeer herding, all Sámi knowledge and philosophy is activated.

The particular memory I subconsciously held onto was of the one day my father wouldn’t let me go with him as he was setting out. I begged, and in the end, he let me join. We drove to the police station in Hammerfest and were met by a high-ranking police officer in full uniform. My father was called to the police station in Hammerfest because the reindeer were found eating flowers in the town. There was a lot of persecutions against us when I was growing up, and still to this day, because the majority of the local community doesn't welcome us there. So the reindeer's presence was and still is, persecuted both socially and legally. People press legal charges against the reindeer owners and the politicians and police enforce these.

We sat in this massive brick building, behind a table facing the police officer in full regalia. At that time, I was very young and not big enough to understand the notion of colonial power-supremacy, but I do remember vividly how my father changed in front of my eyes — his posture, his voice and his gaze. But the most unsettling thing —what really stuck with me — was that his smell changed.

When I started working with the concept of gapmu – this intuitive intelligence system centred in the gut, I was reminded of the reindeer when they’re rounded up in the corral. We have a specific word ‘váivahuvvon hádja’, that describes the scent of reindeer when they’re stressed or scared, for instance when they’re herded into fences or to trailers for slaughter. I began thinking of this as a language, and asked: ‘Why is that memory of my father’s smell so vivid?’ I started looking at the mechanics, where scent acts as a form of communication. In the case of the reindeer, it acts as a warning, telling other animals that a place isn’t safe. When the váivahuvvon hádja, the smell of fear has been stuck to the ground, it’s very difficult to get other reindeer to enter the corral. Looking back at this today, in the context of the Turbine Hall work, I appreciate that my memory is an important notion of Indigenous philosophy and science. For me, using smell is a way to tap into that kind of deep instinct and memory, to remind us that biologically, energetically, spiritually, we are still connected and scent acts as one language that naturally operates between us and across species. Understanding this, I could finally make sense of that childhood memory... Humans are also animals. We have that same mechanism and we are connected to other forms of life around us. In that moment with my father, I was given all the information about fear, danger and discomfort, but I wasn’t able to receive it. In retrospect, I acknowledge that we are given information from our surroundings, probably all the time, but as a species, we need to navigate back to understanding it. In the current global, ecological crises, I find it interesting to ask, what is nature telling us about current human ways of being?

Ánde Somby

It is traditional thinking that we live only in this brief moment—a blink of an eye. We have ancestors: great-grandparents. We reflect on how they solved problems and overcame obstacles, and we feel gratitude for their efforts. For example, I am grateful that they preserved languages and joiks, so that I can joik now. That is the honour and work of the ancestors. I am the fourth generation here. Beyond me, there are three generations to come — children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren — and I have a responsibility to care for their place and being.

Máret Ánne Sara

The way I have learned it, Joik is not only about the act of singing, chanting or the act of making the sounds. It is about channelling the energy and essence of what you are joiking, whether it’s a person, place or animal, and allowing that energy to enter you. For example, if I were to joik my son, I would try to connect with his energy and spirit, his personality and his nature, and then try to express that holistically through a joik, a luohti. But I think it’s important to say that we don’t always have to explain the content of what’s happening in Juoigan, in joiking sessions Joik’s role is about sharing information and energy, often beyond words. It’s deeply spiritual.

Mihkkal Niillas Sara

It is a fundamental part of Sámi thinking to consider future generations. This aligns with the belief that wrongdoings can affect your descendants for up to four generations.

This broad perspective is also reflected in many animal stories. For example, when hunting, you might think everything is controlled by your own consciousness. However, in Sámi thought, the environment — including animals and all the life around you — absorbs your thoughts. If you believe too strongly that you control everything, you may fail in your hunt. This careful awareness of your surroundings remains part of daily life. For instance, if you single out a certain reindeer with the intention of slaughtering it later that mindset could be seen as devaluing a living animal, and could ultimately lead to the reindeer being lost.

While it’s not certain whether the reindeer can hear your thoughts, it may perceive them on some level, leading to outcomes different from your original plans. Johan Turi wrote very clearly about wolf hunting and why hunters should adjust their thinking from the very beginning, so their mindset does not bring bad luck to the hunt. This philosophy acknowledges that life extends beyond what is immediately visible. Much exists in the environment that remains unseen, encompassing the present, the future, and the world beyond human perception.

Ellán-Ánte Ánte

I’ve learned that if you’re going to slaughter a reindeer, you shouldn’t talk about it too much beforehand. If you decide too firmly in advance, the animal might be lost—it might not even be there when you arrive.

I experienced this myself once, and it’s the only time in modern times a wolf has entered our reindeer herd. It was about ten years ago. I had firmly decided on one reindeer to slaughter, the biggest ox with the largest horns in the entire herd. It was big and strong, and I had even said out loud that I was going to slaughter it. But the morning I came to the herd, a wolf had been there during the night and taken down that big bull, eating half of it. I’ve also heard similar stories from our people. My late grandfather used to say he knew someone who, if they ever said out loud which reindeer they planned to slaughter it would be lost.

I understand it as the environment being able to hear you — to listen to your thoughts and actions. Háhtešeatni and Njávešeatni also come into the picture here. You have to be mindful of how you think and act because there is something that registers your intentions, thoughts, and actions. This is all part of Sámi indigenous philosophy and understanding of the world.

Máret Ánne Sara

In Sámi, doalli means a path – an instinctual trail that animals recognise and follow. If we agree that we are part of nature, then we are also animals, and then we are also able to navigate instinctual trails. If both chaos theory and native science recognise that everything is connected, that every action matters, and even the smallest gesture can ripple outward in surprising ways. Isn't there a great potential for humans and our “butterfly power”? In our ability to listen, think, create and act? Can we rethink or re-remember the role we play as a human species on earth? And from that, what is our butterfly power to shape a different future?

Audio clip 4

This conversation considers the ecological impact of ‘goavvi’, as herders negotiate the tensions between government herd-management policies and Sámi principles of balance.

Máret Ánne Sara

My first experience with goavvi, was when I was 13 years old. It was spring on the tundra and I remember that my Dad seemed furious, but I didn't know why. His voice was hard. His movements sharp. He wouldn't look at me, wouldn't meet anyone's eyes. And deep down I thought that was okay. Because I didn't want to look into his eyes, into the black fury that I didn't know the depth of. He started the snowmobile and drove out again. It was blowing cold and the sky was heavy. The tundra was packed with hard snow and I was left alone standing there. Something was very wrong, but I couldn't understand what. I don't quite remember what I did after that, while I was waiting for dad that spring day in 1997. But I remember well when he came back. He was even more abrupt as he jumped off the snowmobile and went to the sled that was attached to the back of the snowmobile. He threw severed reindeer heads, picked them up one by one from the sled and tossed them onto the white snow. Dozens of them. Empty eyes, staring at the endless sky. I don't actually remember anything more until I'm back home in Guovdageaidnu, at my mother's, who is trying to explain to me what happened.

- They order us to cut off the heads of the dead reindeer to take as evidence to the authorities she explains. So they'll believe us. Dad has to do it so he might get some compensation, money to live on next year. You see, it's goavvi, a very bad winter, and the reindeer are dying. Even the big and strong reindeer. They can't get food because of the hard snow. That's why Dad is the way he is now. He’s scared and frustrated.

As an adult, I learned that Goavvi is a snow condition that locks pastures, cutting animals off from their food. It’s becoming more frequent today because of the increasingly unstable environmental conditions in Sápmi, where temperatures swing rapidly from minus 30 or even minus 50 Celsius up to several degrees above zero Celsius. We used to have very stable, cold and dry winters, but now the climate is changing and we have wet winters with very extreme fluctuations in temperature. When temperatures rise or when rain falls on existing snow or even on wet ground, it forms crusts of ice on the ground or throughout the snow, which prevent animals, including reindeer, from accessing food on the ground. This leads to starvation of animals. For me, goavvi represents the reality that we’re living in, but it also parallels the extreme ecological situations unfolding globally.

John Andreas Utsi

Goavvi can begin as early as the fall if certain weather conditions arrive. For example, if it snows early and then the weather becomes mild, it causes problems. The ground moistens and then freezes, creating difficult conditions for grazing.

Another cause of goavvi is when snow falls on warm ground. This can create an ice layer, called skárti, at the bottom. Although there may be lichen underneath, the frozen ground makes it inaccessible to the reindeer. The ice traps the lichen beneath the ground, so even if conditions above look good, the reindeer cannot eat.

As winter progresses, if we experience járvá (snowdrifts), it can become čearga — a compacted, layer of ice all the way to the ground. This layer can grow five to ten centimetres thick as it is now, making it too hard for the reindeer to break through. They cannot dig through to reach the food beneath. Because breaking through this compact ice requires more energy than what the reindeer gain from the food, they tend to avoid such areas altogether and start searching for better grazing ground.

If these conditions arrive early in autumn, they affect the reindeer’s ability to fatten up before winter. If it continues, the only way to improve the situation is heavy rain that melts all the snow down to the bare ground. But this is also risky — if the wet ground freezes, it forms another ice layer.

To counteract this, warm winds are needed to dry the earth, followed by dry conditions and deep cold. When dry deep cold comes and it is followed by snow fall, it creates good grazing winter conditions. The snow becomes seatnjut — snow like sugar — which is easy for the reindeer to dig through.

Máret Ánne Sara

Inger Marie Gaup Eira explains that ‘Goavvi is a condition that affects both the livelihood and the psychosocial well-being of herders. In the years following a goavvi, the calf production (miesehis jagit) decreases, the calves born are more vulnerable because the females produce less milk, and the herd is more vulnerable to diseases. There is no word for goavvi in the Norwegian language; a term often used is beitekrise (grazing crisis). The term refers to poor grazing conditions but does not contain an explanation for why the conditions are poor.’

John Andreas Utsi

The problem has increased noticeably. In the past, the bearta, which means wetlands, were quite dry, which was seen as a good sign and called a bearka autumn. For many years, frozen puddles were a major issue — the reindeer couldn’t find water because the puddles froze early, even before the snow arrived. However, the rivers remained unfrozen, so the reindeer could still manage.

Now, with snow coming so early and the inland climate resembling that of the coast, sudden snowfalls of 10–20 centimetres can happen early in autumn. When that happens, you can be sure that a few mild spells will follow during the autumn season. The first is golggot njázut (October warmth), though the exact timing can vary. Then comes hällemas njázut (November warmth), and typically, around Christmas, there is another warm period.

It’s normal for there to be a day or two of warmer weather, but when warmth lasts for a week or more, it severely damages the snow conditions for grazing. Sometimes, a combination of rain and wind can ruin grazing conditions within just two days.

Some years, we’ve been lucky enough to see weather that repairs the goavvi conditions in the snow. The elders used to say that nature will heal itself. But nowadays, with such severe and sudden shifts — warm rain, followed by very cold weather—I don't think that's ever been common before. In my time as a reindeer herder and from what I’ve heard, the weather here used to be much more stable. That stability created good snow conditions for digging and grazing, allowing the reindeer to thrive.

Ellán-Ánte Ánte

In the last five years, more or less every year has been a goavvi year. Last year a large amount of snow fell unusually early. The snow iced over during autumn, almost like spring conditions. Then, all the snow melted and didn’t return until early December. After that, things went well — the ground froze as it should, there were no ice layers, and the snowfall was steady and good.

But then, in the new year, heavy rain began around the twentieth. It rained for several days. In February, it rained again once or twice, and temperatures often stayed above freezing.

Máret Ánne Sara

Reindeer herders say that the ice quality seems poorer nowadays, and it’s hard for animals to predict such circumstances. The reindeers follow their instincts and routes, and herders have to do their best to protect the animals and themselves. Still, we have had several tragic incidents in recent years. Last winter a herd broke through the ice while crossing a lake in Guovdageaidnu, my hometown, and around two hundred reindeers drowned.

Ellán-Ánte Ánte

A large part of the herd was pressured into a dangerous area — between the lake and the fence — where many hazardous streams run. When they tried to cross the lake, the ice broke beneath them. The reindeer fell through and drowned.

When the sudden heavy snowfall arrived, the fences were quickly buried. Then came rain, followed by cold weather that created cuonju — an ice crust on top. However, the lakes themselves did not freeze solid enough to support the weight of the reindeer.

Máret Ánne Sara

Perhaps I was twelve. It was autumn, and we had brought the reindeer from Fála, our summer grazing island, to the mainland. In the fence facility where we mark calves and take out animals for slaughter, hundreds of calves were confined in an enclosure meant for slaughter animals. They grunted incessantly. I knew it was because they were scared, calling for their mothers, who were separated from them. And the smell, that distinct, piercing smell from the animals, summoned an eerie feeling in the air.

Dad says we slaughter bulls — big, fat bulls with large pieces of meat — not calves, unless they are injured or very small and unlikely to survive the harsh winter. A small calf has little meat. Ideally, calves should grow up so we can observe their characteristics, which are important for a strong, resilient herd. So why were all these little calves being slaughtered? Who insists on eating only calves, and why?

During a break from the hard work of vaccinating, marking calves, and pulling out animals for slaughter, we rested by the fire in our lávvu, grilling marrow bones in the dying embers. The marrow melted on my tongue while the calves’ cries filled the air outside, caught between us and the female reindeer — their mothers. They also grunted incessantly, a chorus of longing. Their entire being — the smell, sounds, movements, gazes — everything was so powerfully communicated, but I was yet not ready to acknowledge this language that speaks to my entire being without a word.

“We’ll see how many manage to run away before tomorrow,” Dad said. I couldn’t tell if he thought it was good or bad if the calves escaped before the slaughter trailer arrived. It seemed he was a bit of both, though escaped calves would mean a lot of hard work for nothing.

How would they get out? They are locked in a fence aren’t they? I wondered. “Ohkoladdet,” Dad said. That means that they long too much. Mothers and calves search and call for each other relentlessly, and the mother refuses to leave her calf. Eventually, the calf finds small cracks or holes and crawls out—back to mom and back to life.

“We used to have many strong bulls,” Dad said.

And yes, I do remember from when I was younger, the big, scary, beautiful, and majestic bulls that you had to watch out for in the corral. The strong ones, who dug through the snow in winter when calves and females were too tired to reach the food beneath. It was true — now, we have almost none left. There was longing in Dad’s voice as he spoke, and I wondered why we didn’t just do what was best for the herd’s collective survival — and thus also for us. Dad didn’t answer, and it would be many years before I understood the state reindeer herding agreement from the 1970s, of which the Norwegian state took control over Sámi reindeer herding. About Agricultural models that were imposed on nomadic Sámi herding, with politically controlled meat prices and financial calf subsidies that steered the herd structure toward small, fragile calves in the harsh Arctic tundra instead of mature reindeer. Or a Čáppa eallu as we call it, a beautiful herd.

Nils Oskal

What kind of a term is Čáppa eallu? Is it an aesthetic concept? Is it a moral concept? Or is it something that belongs to the concept of survival? Some kind of economic basis for what is beauty? I think it’s both aesthetic and moral. A herd lacking calves or mature bulls feels unsettling because it signals imbalance and vulnerability. What kind of herd is that? To understand beauty we need to take a step backwards. What is the meaning of beauty, when you say something is beautiful. It's the same as with boazolihkku. What kind of beings are we if we have boazolihkku? A beautiful reindeer herd, what does that tell us about ourselves?

Máret Ánne Sara

From a reindeer herding Sámi perspective, I have learned that a beautiful herd is a strong, resilient and thriving herd. It refers to the mixture of animals with certain personality traits and skills that the herd collectively hold. These traits take time to grow and to be seen — herders cannot see them in calves necessarily, but through interaction over time, these traits become apparent. An important part of a herder’s responsibility is to recognise and nurture these characteristics in the herd.

Today’s government subsidies are being offered for calves, in line with industrial farming practices which seek to generate the highest amount of profit. Due to high living costs in modern society, herders are being pressured to reconfigure their herds, increasing the number of female reindeer to produce calves. A practice that goes in direct conflict with Sámi knowledge and philosophy, which also takes an ethical toll on Sámi herders and the reindeer herding community. Strong reindeer herds are comprised of a mixture of male reindeer, female reindeer and calves, but, since reindeer numbers are strictly controlled by the government, this results in the sacrificing of the bulls, who have the physical strength to break through thick ice in difficult winters to access the food beneath. The result is that the herd is less able to access food and protect itself from predators, making it weaker and more at risk.

Mihkkal Niillas Sara

A beautiful herd reflects not only the reindeer’s condition and overall wellbeing, but also your skill in managing the structure of the herd — your knowledge, commitment, understanding and evaluations, which differ according to the breed of reindeer you have, and can even reflect your history as a reindeer herder and the practices and knowledge passed down to you through the generations.

Ultimately, the responsibility for the herd’s wellbeing lies with you. While it’s possible to accidentally lose reindeer, it would still raise the question of why you lost them. But if your herd is not thriving, you might find yourself subject to commentary or criticism concerning your management. Internal criticism is common within reindeer husbandry. Sometimes you might hear about individuals who ‘collect’ reindeer without adhering to foundational values regarding herd management. That invites scrutiny.

Government policies have also been criticised for influencing the types of reindeer people choose to keep or sell, and for pushing herders towards more homogeneous herds. These policies have often focused on a production-oriented approach, which means maintaining a large proportion of female reindeer to produce calves every year. From this perspective, a rotnu – a female without a calf – would not be considered ‘beautiful’.

However, from the perspective of the Sámi reindeer herder, a rotnu can be very beautiful if it is in good condition — if, rather than producing calves annually, she has been allowed to invest in her own strength and condition in certain years. Such females may develop important features, like large, strong antlers, and hold significant value within the herd. This perspective challenges governmental ideals that define beauty solely based on meat production.

Mari Boine

My songs are born in the conflict between Indigenous philosophy of life and a culture of greed that has eternal growth as its mantra. In my songs I have shared stories about what it's like to be a human being in the middle of this conflict. In my lyrics I continue asking why, while I observe that my people lose trial after trial because among other reasons it is hard to prove that we have been here for thousands of years because our culture and dwellings left few traces. It is an irony of faith that the fact that our culture was sustainable creates problems for my people today. Some claim that in order to succeed in the modern world, we need to leave all the old ways behind. I belong to those who think we should take with us the best from our ancestral heritage. And there to take it with us into the new world of technology and science. My music has always consisted of old traditional elements and modern musical expressions.

My dream is a future where the best of science can meet the best of indigenous knowledge with curiosity and with respect and that together we could build a more sustainable world.

Máret Ánne Sara

As I stood here in August 2025, in The Turbine Hall, this former coal and oil power station; a symbol of the extractivist and capitalist systems that have helped fuel today’s global ecological crisis, I was laying out symbolic goavvi layers with reindeer hides entangled in power cables, while I was watching a livestream on my phone, of my godfather being arrested while demonstrating to stop the Nussir copper mine at our shared reindeer pastures. That mining project is blowing up mountains on sacred calving lands and has, by Norwegian authorities, been granted permission to suffocate a healthy fjord by dumping thirty million tonnes of toxic waste into the sea. The Norwegian state authorities justify it through the language of the climate crisis, claiming the need for minerals to fuel ‘climate-friendly’ consumption. Yet behind this argument lies the same old extractivist logic, the same cycle of exploitation.

Alert to the Sámi philosophical notion that one's mindset can pose a threat to the outcome of a situation, I choose not to argue within the rationality of capitalist awareness. Instead I bring Indigenous science, where innovation is inseparable from respect for life, into this space and time to allow us to reflect from the position of nature, and of life itself. What is power, energy, wealth, or even knowledge, truly?

I have named this work Goavve-Geabbil. The first part, Goavve- refers to those winter conditions which symbolise the severe challenges we face today, due to modern human logic and behaviour. The second part, -Geabbil, invites you to enter into, and attune yourself to the intellect of nature and into Sámi philosophy and the Indigenous cosmos.

Years ago, I read about a study where scientists at NTNU in Trondheim were exploring energy efficiency by studying animals adapted to extremely cold environments, particularly in the Arctic. The study concluded that the reindeer’s nose is a supremely intelligent and efficient structure. In freezing temperatures, it retains moisture and heats inhaled air to around 80 degrees celsius within a second. It’s a powerful example of nature’s intellect, creativity and engineering — and a humbling reminder to modern science and human capacity.

I've chosen to create the internal structure of the reindeer nose into a huge physical maze, which you are invited to enter and explore with your set of tools, meaning your own body and all your senses. This is the context of Indigenous science, where you as a human are not physically bigger than, or superior to the animal’s nose, but where you can get lost, become disoriented or even humbled, or at least experience bodily inferiority in the meeting of natural materials and concepts that transcend language and defy industrial logic.

Gregory Cajete states that: ‘Native science is the collective heritage of human experience with the natural world…while modern humans may have technical knowledge of nature, few have knowledge of the non-human world gained directly from personal experience.’ I would argue that as long as we are still dependent on nature for life, this rare knowledge is highly relevant for all of us, and to preserve it, totally depends upon Indigenous people’s right and ability to live within their lands and ways.

In Sápmi, we say that in order to see outward, one must look inward, and to find the way forward, one must look backward. The perception of Indigenous life as something ‘primitive’ or outmoded is arguably itself outmoded. In our quest for a sustainable future and life, maybe it is time to look backwards and recognise Indigenous knowledge systems as profoundly progressive and essential frameworks for the custodianship and future of our shared world.

Reindeer Herding

In Sámi, the verb eallit (‘to live’) shares its root with eallu (‘herd’). Reindeer herding is more than an economic activity; it is a way of life that connects Sámi people to the rhythms of the land and cycles of nature. It is legally recognised as a protected cultural practice, carrying centuries of knowledge, language, stories, and spirituality.

Unlike industrial farming, which often restricts animals’ movements and controls their feeding patterns, reindeer roam freely across vast landscapes following seasonal migrations routes. Sámi herders dedicate their lives to safeguarding the reindeer and their environment. In turn, the reindeer sustain them by providing food, clothing, tools, and shelter. This partnership is based on balance and respect: taking only what is needed and ensuring nothing goes to waste.

In the 1970s, reindeer herding in Norway shifted from an autonomous practice to a state-regulated sector. Over the following decades, policies were introduced to restrict herd sizes, define grazing districts, and permit industrial projects such as mining and wind power on herding lands. In 2012, the government issued herd reduction orders in Finnmark, Norway’s northernmost county, claiming that overgrazing by reindeer was damaging vegetation. Many herders and scientists disputed this claim, pointing instead to the environmental damage caused by industrial development. Sara’s brother, Jovsset Ánte Sara, was instructed to slaughter nearly 40% of his herd. In 2016, he brought a lawsuit against the Norwegian state, arguing that the culling order violated his human and cultural rights.

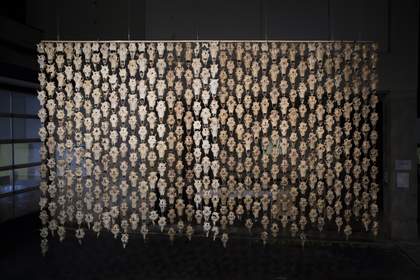

To support the case and raise public awareness, Sara created Pile O’Sápmi, 2016. On the morning of her brother's trial, she stacked 200 reindeer heads from the slaughterhouse outside the court, topping the pile with the Norwegian flag. The work later evolved into Pile O’Sápmi Supreme 2017, composed of 400 reindeer skulls suspended in rows to resemble the Sámi flag. In the centre of each skull was a bullet hole, a physical trace of the state mandated culling. Sara’s brother won two trials, but in 2017 the Norwegian Supreme Court overturned these verdicts. In 2024, the UN Human Rights Committee ruled in his favour, recognising the violation of his rights.

The Arctic is warming at a rate four times faster than the global average. In this rapidly changing climate, reindeer herding is vital for managing vegetation, promoting biodiversity, and regulating the temperature in Sápmi. Guided by generations of knowledge about weather, grazing, and migration routes, Sámi herders help to support ecological balance—one that sustains cultural traditions while safeguarding both the reindeer and the fragile landscapes on which they depend.

Máret Ánne Sara, Pile O'Sápmi, Tana-Deatnu, 2016. (Photo © Iris Egilsdatter)

Máret Ánne Sara, Pile o' Sápmi Supreme, 2017 (Photo © Annar Bjørgli/ Nasjonalmuseet)

Audio Description

Listen to an in-depth visual description of Máret Ánne Sara’s Hyundai Commission, Goavve-Gebbil.

This is an audio description of the 2025 Hyundai Commission: Goavve-Geabbil, [GWAH-vee GYAH-beel] created by artist Máret Ánne Sara.

Sara is a member of a Sámi reindeer herding family based in Sápmi. This is the traditional territory of the Sámi people, today divided between the nation states of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia.

Sara’s Commission takes over the Turbine Hall, the huge space at the centre of Tate Modern. The Hall ceiling stretches high above your head, with a wide central skylight running along its centre. The floor beneath you is a lightly reflective grey concrete, which slopes gently upwards at the west of the Hall towards the main entrance and exit. There is a tall window in the centre of this wall, above the entrance. A wide bridge platform spans the middle of the Hall, providing an elevated walkway between the two sides of the gallery.

You can access this space from different entrances and at different levels. In this audio description we begin at the top of the wide concrete slope, near the main entrance.

At the exact centre of the slope is a tall structure, suspended from the ceiling. It is approximately 28 metres high and 2.5 metres wide. It is fixed to a metal baseplate on the floor. Positioned horizontally from the top to the bottom are irregularly shaped objects, arranged like the rungs of a ladder. There are 72 objects in total, arranged in 27 rungs. They are reindeer hides. Each rung is two hides wide. The gap between each rung varies vertically, but is around half a metre on average. Some of the hides are arranged at a diagonal angle. One side of each hide is covered in thick, bristly hair. Some of the hides are pure white, others a dark brown, some a marbled mixture of the two.

Where visible, the rear of each hide is covered in dark red splotches, resembling the cover of an ancient book or map. Some of the hides are folded in on themselves. Others are hung as a pair of two open hides with their hair-covered sides stitched together, and their leathery skin exposed to the visitor. There is no obvious pattern to how the hides have been ordered.

This is ‘Goavve-’ [GWAH-vee], the first part of Máret Ánne Sara’s artwork. 'Goavvi’ is the Sámi name for a snow condition caused by extreme temperature fluctuations brought about by climate change. Rain and melted snow freeze into layers of ice on the surface of the land. This prevents animals like reindeer accessing the food underneath and is causing widespread malnutrition and starvation among these species.

Through her work, which includes sculpture, installations and performance, Sara aims to raise awareness of Norwegian colonialism on Sámi ways of life. Reindeer herding is a cornerstone of Sámi culture, and materials from this practice, including bones and hides, are a key part of Sara’s work.

As you approach the artwork, you notice a potent smell. This has been created by the artist in collaboration with scent-maker Nadjib Achaibou, and in consultation with Grace Boyle/The Feelies. Sara was inspired by the scent released by reindeer when they are scared, as a biological warning signal. Breathe in deeply. Can you smell fear?

You can walk around the whole structure and get close to the hides, but please do not touch them. Tactile samples of the hides and other materials used to make the Commission can be requested from members of our Visitor Experience team. Please ask a staff member nearby.

The hides occupy the whole of the structure. Hanging vertically, from the ceiling to the floor, are a mixture of white, grey and silver electrical cables, around 2 centimetres thick; heavy metal chains each 3 centimetres thick; stainless steel cables; and long tubes of LED lights. One of these tubes glows a warm, yellowish light. The other two are a bright, cool white. The chains are a weathered blackish grey. The straight vertical lines of the cables, chains and lights weave irregularly behind and in front of the horizontal hides, like the warp and weft of a tapestry.

If viewing the structure from the bottom of the slope, the order of the vertical materials from left to right is as follows:

Steel cable, chain, cool white LED light, white electrical cable, silver electrical cable, steel cable, grey electrical cable, warm white LED light, chain, steel cable, silver electrical cable, steel cable, cool white LED light, white electrical cable and steel cable.

The light from the LED cables catches the fur on the edge of the hides, making their outlines gently glow.

The cables are perhaps a reference to the intensive and continued expansion of mining and energy extraction imposed on Sápmi, but also the wider degradation of land and ecosystems across the world. The hides, however, embody a different form of power, one grounded in ancestral knowledge and spirit.

Move down the ramp and towards the east end of the Hall. Fifty metres or so after the slope ends, you pass under the wide permanent bridge platform at the centre of the Turbine Hall. As you do so, take a moment to listen to the soundscape that fills the space, which the artist has designed in collaboration with Kristine Hansen. There are recordings from the Sápmi landscape as well as examples of joik. This is the Sámi musical practice, which uses voice to evoke the essence of a person, animal or place.