Hyundai Commission: El Anatsui: Behind the Red Moon, Installation View, Photo ©Tate (Joe Humphrys)

Introduction

Each material has its properties, physical and even spiritual.

El Anatsui

Staged as an artwork in three acts, El Anatsui’s cascading metal hangings transform the Turbine Hall. Thousands of repurposed liquor bottle tops and metal fragments were crumpled, crushed, and connected by hand with copper wire into unique compositions. Later, large sheets were pieced together to form massive abstract fields of colour, shape, and line. Despite being monumental in scale, the works are flexible and adaptable to change. Descending from the Turbine Hall’s ceiling, Anatsui’s symphonic sculptures hang in the air and seem to float across the space.

You are invited to embark on a journey of movement and interaction through the hangings, a dance between bodies and sculptures. Anatsui’s free-flowing forms challenge the building’s industrial scale and open up different ways of looking. Viewing the hangings from afar reveals a landscape of symbols: the moon, the sail, the earth, and the wall. Up close, the logos on the bottle tops speak to their social and material life as commodities. As products of a global industry built on colonial trade routes, they connect the overlapping histories of Africa, Europe and the Americas. Revealing the poetic possibilities of his materials, Anatsui explores the entangled relationships and geographies that bind us together.

ACT I: THE RED MOON

Hyundai Commission: El Anatsui: Behind the Red Moon, Act I The Red Moon, Installation View, Photo © Tate (Lucy Green)

Hyundai Commission: El Anatsui: Behind the Red Moon, Act I The Red Moon, Installation View, Photo © Tate (Lucy Green)

The Turbine Hall reminds me of a ship. I was thinking about motion and the idea of the red sail. This work addresses a history of encounter and the movement of ideas and people.

El Anatsui

The first hanging on the ramp resembles a majestic sail billowing out in the wind. Ships have transported people and goods around the world since ancient times. During the transatlantic slave trade, enslaved African peoples were sold and exchanged for gold, sugar, spirits and other commodities. They were then taken across the ocean towards the Americas, with many labouring on sugar plantations that fuelled the alcohol industry. Later, spirits produced in the Caribbean would be shipped to Europe, and from there to Western Africa. The bottle tops used in this commission derive from a trade network of present-day commodities rooted in colonial histories.

This red and yellow sail might announce the beginning of one such journey across the unforgiving waters of the Atlantic Ocean. At the height of the transatlantic trade in the 18th century, sailors would sometimes use the moon to guide their journeys. Its gravitational tug as Earth’s natural satellite also sets the rhythm of the ocean’s tides. Here, red bottle tops form the outline of a red ‘blood’ moon, seen during a lunar eclipse. Elemental forces interweave with human histories of power, oppression, dispersion and survival.

ACT II: THE WORLD

Hyundai Commission: El Anatsui: Behind the Red Moon, Act II The World, Installation View, Photo © Tate (Joe Humphrys)

I use multiple elements to talk about the world: not a world made up of just one culture, but a world shaped by all of us coming together.

El Anatsui

The sculpture in front of the Turbine Hall bridge is composed of multiple layers. They suggest a loose grouping of human figures, suspended in the air in a state of movement. When viewed from a particular position on the bridge, the fragmented shapes converge into the single circular form of the Earth. The circle echoes the red moon of the sail as a fellow celestial body. Anatsui has a longstanding interest in the fragment as a symbol of renewal and restoration. He has said that ‘breaking is not destruction but a necessity for reforming.’

As separate elements, the group of restless human forms might imply dispersion through the migration and movement of people across the globe, both forced and voluntary. When viewed together, the fragmentary circle gestures towards new formations of collective identities and experiences. Anatsui also plays with the tension between transparency and opacity. The ethereal appearance of the figures is achieved using thin bottle top seals wired together to create a semi-transparent, net-like material.

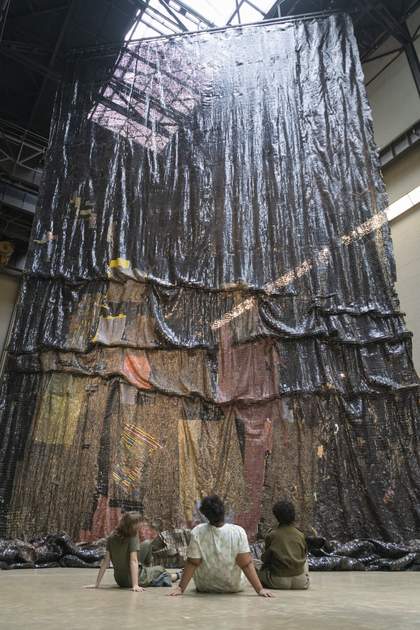

ACT III: THE WALL

Hyundai Commission: El Anatsui: Behind the Red Moon, Act III The Wall, Installation View, Photo © Tate (Lucy Green)

Hyundai Commission: El Anatsui: Behind the Red Moon, Act III The Wall, Installation View, Photo © Tate (Lucy Green)

Tate & Lyle sugar was the only brand we used during my childhood in the Gold Coast. I came to understand that the sugar industry grew from the transatlantic trade and the movement of goods and people. My idea is to play with all these elements.

El Anatsui

In this final act, a monumental black wall stretches from floor to ceiling. Anatsui’s interest in walls is rooted in the ancient story of the earthen wall of Notsie (present-day Togo). Built by King Agokoli to confine and oppress his subjects, a revolutionary uprising by the Ewe people led to the wall’s destruction and the Ewe’s escape. As well as structures that constrain and encircle, Anatsui also speaks of the productive quality of walls as ‘... an attempt to hide things. They provoke curiosity and curiosity might get imagination out to the other side.’

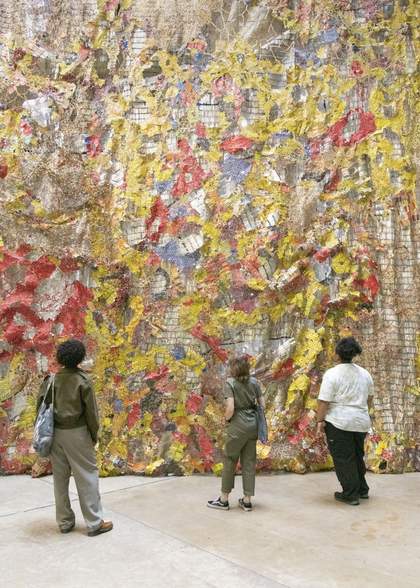

Facing the yellow back of the sail, the wall might suggest an arrival at shore. Metal pools rise from the ground at the base of the wall, resembling crashing waves and rocky peaks. For Anatsui, the use of black refers to the continent of Africa and its global diaspora, charged with the potential of homecoming and return. Moving behind the wall reveals an edifice of shimmering silver, covered in a multi-coloured mosaic. As lines and waves of blackness and technicolour meet, they echo the collision of global cultures and hybrid identities that Anatsui invites us to consider throughout the commission.

ABOUT EL ANATSUI

Hyundai Commission: El Anatsui: Behind the Red Moon, Installation View, Photo © Tate (Lucy Green)

At the centre of Anatsui’s artistic practice is a longstanding interest in humanity’s disruption of the Earth’s natural order. His artworks engage with histories of connection and displacement, transforming commonplace materials into vast sculptural compositions. When working with bottle tops, sourced in Nigeria, the artist reckons with ‘the material which was there at the beginning of the contact between two continents.’

Anatsui is aided in his studio work by dozens of assistants. They work together to stitch and assemble his sculptures by hand. Connections are made organically between materials, shapes and colours as compositions are pieced together. The flexible hangings which emerge embody Anatsui’s idea of the ‘non-fixed form’ - they can appear in different arrangements at each separate installation. Anatsui’s work also engages with global histories of abstraction. ‘When I started working with abstraction, I saw the freedom and the challenge that comes with it,’ the artist has said. ‘You are not contributing to the world by replicating what is there already.’

El Anatsui was born in Anyako, Ghana in 1944. He currently lives and works from Tema, Ghana and Nsukka, Nigeria.

Audio description tour

This in-depth tour has been created with visually impaired visitors in mind, but can be enjoyed by anyone.

Introduction

Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall definitely lets you know that nobody is promising beauty or refinement here. Today, that doesn’t quite apply. I think you will discover some beauty here. Quite a lot, in fact.

The Turbine Hall has taken on an entirely different character with this artwork. The name of the artist invited to present here is two words - the first is spelled E-L, and the second is spelled A-N-A-T-S-U-I (pronounce). This is a name from Ewe - a language used in the southern coastal area of Ghana.

El Anatsui is an artist who has been helped by as many as 200 assistants, whom he refers to as ‘Artists’. I understand that it is people in the area where he works in Nsukka Nigeria that help him to make and assemble the material from which this work is assembled. El Anatsui describes his artworks as ‘hangings’ and also as ‘sculptures.’

The title for the Turbine Hall display is Behind the Red Moon. The material hangs in three main sections suspended separately from the roof at intervals along the entire length of the Turbine Hall. Two of the sections are like sheets each with two contrasting sides - very different in character - and there is a middle section which is a suspended mobile of clustered shapes. There are five main viewpoints for you to discover.

We will be moving three times during our visit, and we begin at the top of the ramp near the main gallery entrance into the Turbine Hall. Now would be a good time to pause this guide and move to the correct location.

Act I

THE RED MOON:

The Turbine Hall reminds me of a ship

I was thinking about motion and the idea of the red sail.

This work addresses a history of encounter and the

movement of ideas and people.

What El Anatsui puts in front of you, when one enters at the top of the ramp, is a huge square red curtain that billows towards the entrance door. It almost fills the height and width of the hall, and tilts over towards you. There is space to walk underneath as we go down the ramp.

A huge circle of warmly glowing Indian red is speckled with gold, and fills the square, spreading out to touch the middle of all four sides. Around the circle the surrounding surface and corners of the square are a deep crimson; a blood red. 35 meters above you, the curtain is tied to a curving metal rail attached to the roof rafters.

Not only is the ball-like bulge of the hanging material a vast red moon, but people with some experience of sailing in boats will immediately think it is like an enormous sail filled with wind and charging towards them.

Materials

And the sail weighs over 1 ton. It was, appropriately, sailed to the UK from Ghanna in separate sheets and joined by a team of experienced fabricators working here in the gallery. And it has taken many people, I understand that as many as 200 people produced these fabrics from over 2 million bottle-tops. The red sail only uses rum bottle-tops, including Elliott Dark Rum and Squadron Dark Rum. And the sail weighs just over 1 ton. Elsewhere you can meet names that include Rexton Dry Gin, Eagle Stout, St Remy Cognac, Seaman’s Schnapps, Action Bitter, Nigerian Guinness, Lord’s Whisky. The whole display here has big broad effects of colour and shape - but it also has these tiny characterful details.

El Anatsui works in Nigeria and in his country of origin, Ghana. He grew up near one of the forty towers that stand along the short south coast. In the towers enslaved people were kept before being taken across the Atlantic by sailing ships. If they survived the crossing, they were set to work in plantations. Workers in the sugar cane plantations of the Caribbean had for the most part been subjected to this brutal treatment. Now, discarded bottle tops and neglected people are discovered to have a capacity for transformed roles.

The red sail is of great significance. By using only rum bottle-tops it has a very direct connection to sugar can from the plantation. The British then used the rum produced in trading and bargaining, and as an inducement to trade.

Backside of Red Moon

If we move down the ramp, we will find we’re looking up at the other side, seeing a different colour effect, and more in close. And so, the sail will be funneling down towards us on the other side. This side of the sail catches daylight and is also illuminated with spotlights and has a radiant bright golden yellow glow. The effect is of a brightly lit field of intense colour that will be seen clearly throughout the hall. There are variations and pale patches of silver and green and light brown, but they merge easily in the overall expanse of brilliant golden colour. In the centre is a large silvery shape like a wonky letter ‘y’ that reflects the light brightly. A mysterious symbol.

I think he wants us to have minds that are played with rather than matter-of-fact in dealing with this work.

We’re going to move further down, so we’re underneath the middle section.

Act II

THE WORLD:

I use multiple elements to talk about the world:

not a world made up of just one culture,

but a world shaped by all of us coming together.

At the bottom of the ramp here, we have now walked down to the lower level. Immediately above us are a cluster of about 30 translucent shapes suspended in the centre of the hall, and they spread 15 meters on a diagonal across the hall. The first impression is of a cloud, or a flock of birds caught in flight when you first look up at them. The cluster of shapes hovers between you and the yellow sail.

The shapes revolve like an abstract mobile made using a metal wire mesh that has an earthy golden glow, but they are not entirely abstract. It is like a series of glimpses of heads and shoulders that merge with each other and dissolve into their surroundings. There are no complete human bodies and some of the smaller shapes do not have any clear identity as body parts. The metallic mesh that is used does look a lot like chicken wire from down here, of the sort used to make animal runs and cages, for rabbits and birds. But here, it is a beautiful golden gauze that varies in how it catches the light.

Final Component

Front

And now, we go towards the far end of the hall furthest away from the main door - And ahead of us is an even taller curtain of material.

(pause in speaking for a time to allow movement to area)

This one does not bulge or billow and it is dark - mainly black. It seems almost solid, like an immense vertical wall. It is angled away from our approach down the hall and it spreads across the floor in swirling folds and heaps of black material. The surface is like a mosaic of small geometric segments and shapes, much of which is dark and glossy, and yet there are also small areas of precious glowing colour. These patches, the size of large jellyfish, swim and float among the folds. In this section of the display, you can get very close to the material, and then it becomes obvious and clear that these areas of colour are made from large numbers of very small parts of tin containers. The same parts have been put together over and over again, so their colour spreads. The names of products are shown repeatedly in each area of colour. Small geometric shapes of glossy colour joined to make a bendy or undulating surface that is lustrous and luminous.

For El, the use of black often refers to the continent of Africa and its global diaspora, charged with the potential of homecoming and return.

High on the side wall there is a third text by the artist - it reads:

Act III

THE WALL:

Tate & Lyle sugar was the only brand we used during my

childhood in the gold coast.

I came to understand that the sugar industry grew from

the transatlantic trade and movement of goods and people.

My idea is to play with all these elements.

The black wall weighs 3/4 ton. Shall we go round to the other side?

Back

Welcome to the grand finale. Contrasting with the mainly black front wall, here you see a background of silver moonlight, up which a seething swirl of glowing colours sprawls and spreads like a wonderful summer garden bursting with energy. Lots of metal tins and bottle-tops have provided the material that is linked together, into the most amazing abstract expressionist explosion of texture and colour. It is full of movement and variation and a terrific sense of release and joy. This mass of surging beauty is climbing upwards towards the silver sky, and now halfway up from the floor to the top looks like it will continue to climb with a life of its own.

One gets the sense that El Anatsui is someone who has enjoyed playing with the massive stage provided by the Turbine Hall. If you position yourself on the river side of the hall and face back towards the bridge and the entrance, the golden curtain at the far end is still clearly visible and light and colour fills the hall as never before.

El Anatsui has advice to young artists: "Just do it. The golden rule is that there are no rules. As an artist I think your worth is determined by how you can operate without rules."