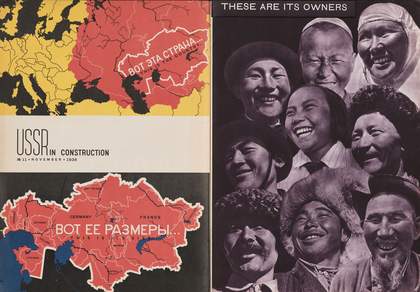

Aleksandr Rodchenko, USSR in Construction, Issue 11, 1935, Journal, Purchased 2016. The David King Collection at Tate

From 1917, the vast Russian Empire was reshaped by communist ideals and power into the USSR, the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics. In the first decade, the people suffered the impact of civil war, famine and the power struggle that followed the death of Communist Party leader Vladimir Lenin. In the 1930s, Joseph Stalin’s totalitarian regime brought economic and industrial advances at the cost of millions of lives. Ordinary citizens as well as eminent figures were killed in political purges. The German invasion of 1941 drew the USSR into the Second World War, termed the Great Patriotic War.

With Stalin’s death in 1953 came the ‘Thaw’, a period of relative liberalisation. Visual culture kept pace with the social revolution. Many avant garde artists believed art and architecture were tools for social change capable of creating a new environment for the new citizen. Art became accessible to millions through prints, posters, journals and photobooks. The resulting imagery appeared across the breadth of the Soviet Union. This shared visual vocabulary came to dominate everyday life, giving rise to a new wave of creative experimentation in the late 1950s.

This exhibition is drawn primarily from the collection of graphic designer David King (1943–2016). The remarkable range of visual material he brought together testifies to the role of the image in shaping history, politics and everyday life for generations of people.

1. Art Onto The Streets

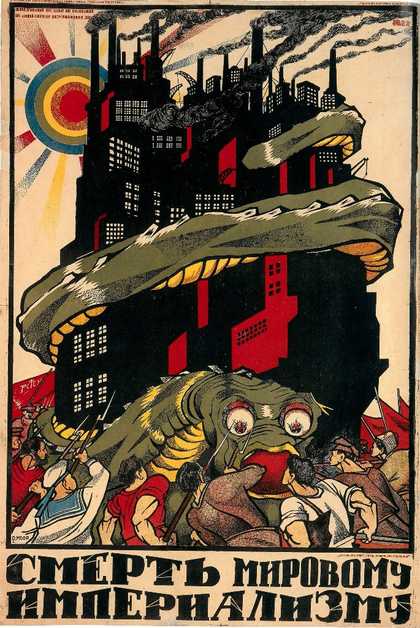

Dmitrii Moor, Death to World Imperialism 1920

Led by Vladimir Lenin, the Bolsheviks swept to power in October 1917. Over the next five years, they struggled to consolidate control over the vast territory reaching from the Baltic Sea in the west to the Sea of Japan in the east. The message that the revolution was putting power into the hands of the working classes was spread around the country through mass media: street posters, newspapers, prints, photographs and the new medium of film.

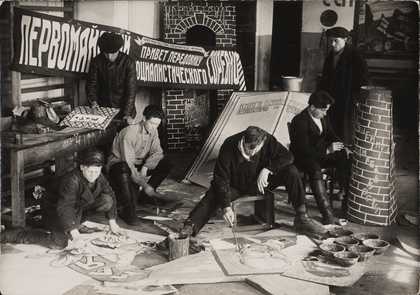

Multilingual posters and proclamations were pasted up on the streets and in railway stations, factories and workers clubs. Political speeches and demonstrations became spectacular events. Agitprop trains, equipped with cinemas, exhibition carriages, mobile theatres and classrooms, brought the message of the new regime to remote regions. At the same time the regime commissioned new monuments that transformed public spaces with memorials and statues celebrating the empowerment of the working class. Foreign governments, fearing for their own stability, watched with hostility and concern.

2. The Future is our Only Goal

El Lissitzky and Sergei Senkin, El Lissitzky's unstoppable photomontage from the catalogue of the Soviet pavilion at "Pressa", international press exhibition in Cologne, Germany, 1928

The mass-produced image – in photographs, posters, journals and books – became the focus of the new artistic culture. Unlike the precious, unique paintings and sculptures owned by the ruling class before the revolution, these formats were widely available. Avant-garde artists led this transformation. This room focuses on artist couples: El Lissitzky and Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, Aleksandr Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova, and Gustav Klutsis and Valentina Kulagina.

Their collaborative practice embodied the spirit of proletarian collective art production. They employed simplified forms and pure colours to forge what they believed would be a truly popular art form. Photography and photomontage – collages from photographs – played a crucial role in maintaining a human presence within the structure of abstraction. The results can be seen here in the array of designs for newspapers, international magazines and photobooks.

These were produced in hundreds of thousands of copies, as well as in more exclusive deluxe editions made for the Communist Party elite. Lissitzky merged image and text into a dynamic visual experience, working closely with Lissitzky-Küppers on book design and production. Rodchenko pioneered new perspectives in photography, transforming the everyday by showing it from unfamiliar angles.

Both Lissitzky and Rodchenko applied their innovative visual sense to exhibition design. Stepanova designed textiles and workers’ clothes as well as vibrant journal layouts. While Klutsis strove to represent political ideals using photography, Kulagina’s allegorical figures emphasised the inherent energy of the manual labourer.

3. Fifty Years Of History

Tsar Nicholas II and Alexandra dressed for the Costume Ball in the Winter Palace 1903. Tate Library and Archive

Zooming in from the epic to the intimate, the fifty turbulent years between 1905 and 1955 can be explored through small-scale objects. From the first rumblings of revolt against the Tsar, through the political, economic and social transformations up to the death of Stalin, these objects offer personal glimpses into the period. Such objects would be found in ordinary homes, each telling an intertwined story of human and national events, from an athletes’ pageant to Stalin’s lying-in-state.

As well as tracing a history, this material demonstrates the complex relationships between politics and art at the time. Reconstructions of significant events, satirical representations of former political leaders and manipulated images reveal how the nation’s story was told differently over time. Beyond mere documents, the objects in this room attest to the role that images played in shaping the history of the period.

4. 1937: A View From Paris

Alexander Deineka, Stakhanovites 1937. Perm State Art Gallery

In 1937, the Soviet Union was prominently represented at the International Exposition of Art and Technology in Modern Life in Paris. Twenty years on from the 1917 Revolution, its national pavilion celebrated and exhibited the country’s recent achievements on the world stage. The pavilion, designed by Boris Iofan, was dominated by Vera Mukhina’s Worker and Collective Farm Woman, a huge stainless steel sculpture that celebrated the solidarity of the urban and rural working classes. Inside, the modernist interior design by Nikolai Suetin showcased innovations in government, science, transport and industry.

The pavilion’s combination of modernist elements and the Party-approved socialist realist style offered a complex response to the challenge of an exhibition dedicated to modern life.

The six halls of the pavilion culminated in a vast mural by Aleksandr Deineka based on Stakhanovites 1937. Deineka’s painting fused reality with aspiration, as his depiction of a parade in Red Square includes the unrealised Palace of the Soviets in the background. The crowd features portraits of Stakhanovite workers, who set records for productivity. Deineka conceived his composition in three parts, with only its central panel being realised as a mural. His accompanying compositions, 1917 and 1937, mapping the historical legacy of the first twenty years of Soviet power, remained in the sketch form seen here. Deineka was awarded a gold medal for his work in the exhibition and the pavilion was visited by some 20 million people.

5. Ordinary Citizens

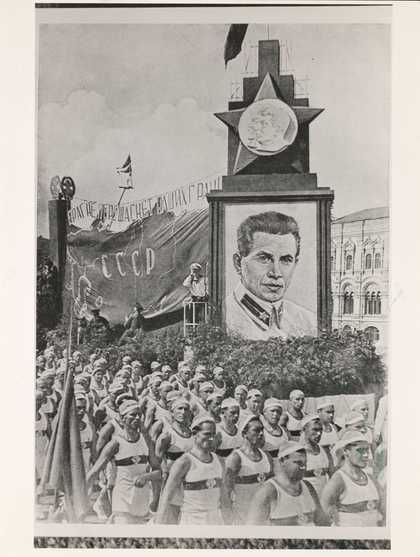

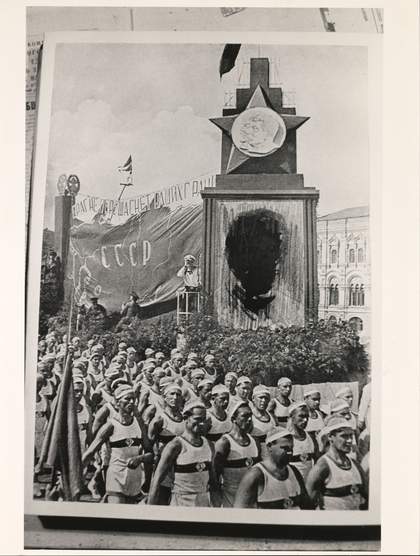

Celebratory procession featuring a portrait of N. Yezhov, head of NKVD in 1936-38 c. 1936-38. Tate Library and Archive

Celebratory procession featuring a portrait of N. Yezhov, head of NKVD in 1936-38. Yezhov's face blacked out c. 1936-38. Tate Library and Archive

The optimistic image projected internationally in the Paris exhibition of 1937 contrasted with the sombre and often brutal reality of life in the Soviet Union. The year marked the peak of Stalin’s Great Terror, during which over 1.6 million people were arrested. Out of these, around 700,000 were sentenced to death and others sent to the Gulag labour camps. This room brings together images that present the official, state-controlled narrative of the period and the intimate stories of some of its victims.

The day-to-day activities of the secret services, OGPU (The Unified State Political Administration), which carried out mass arrests and executions, are uncovered through a sequence of photographs. From 1934 it was incorporated into the NKVD (People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs) and the repressions reached an unprecedented scale. Examples of censored images reveal a massive state-instigated project to eliminate all evidence of the existence of Stalin’s political enemies. Vandalised photographs attest to self-censorship, whereby ordinary Soviet citizens, fearful of repercussions, erased ‘enemies of the people’ from visual material in their surroundings.

The stories of the deaths of three individuals are highlighted: the execution of military leader Mikhail Tukhachevsky as a result of the 1937 trials, the suicide of the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, and the suicide of Stalin’s own young wife, Nadezhda Alliluyeva. At the centre of the room are prison mugshots showing some of the people who suffered in the mass purges. Together they highlight the all-encompassing nature of the Great Terror, in which people of all backgrounds fell victim to repression.

6. The War and the 'Thaw'

Nina Vatolina, I Will Vote for the Candidate's Bloc of Communists and Non-Party Members 1946. The David King Collection at Tate

Following the German invasion on 22 June 1941, Soviet propaganda immediately mobilised citizens into action. The image of Stalin could no longer be expected to inspire unquestioning loyalty and the symbolic figure of the ‘Motherland’ began to replace that of the Leader.

Material featuring patriotic imagery permeated all aspects of life. Viktor Koretsky reworked photographic images into hand-painted designs that were used for poster production as well as postcards, leaflets and even postage stamps. The artists who designed this material came from a generation brought up on images of patriotic resistance created during the Civil War (1917–22), and they drew on this legacy and reinvented it. Nina Vatolina’s painterly poster designs harness the imagery of the empowered woman. The practice of hand-making stencilled posters, also first used at the time of the Civil War, was revived in the TASS window posters (named for the Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union, the nation’s central news agency). Photographers also worked for TASS as army photojournalists. Yevgeny Khaldei’s imposing images were often manipulated to enhance their dramatic propaganda effect.

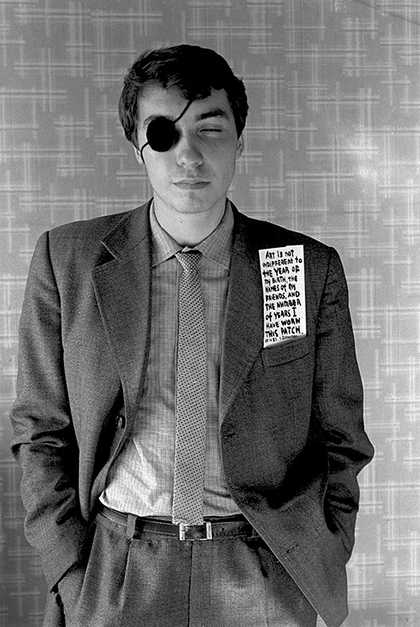

By the middle of the twentieth century socialist realism dominated the visual culture of the USSR – a uniformity which was by turns powerful and overbearing. During the so-called ‘Thaw’ that followed Stalin’s death in 1953, a generation of artists, including Ilya Kabakov, rejected and reworked official imagery in a burst of creative innovation.