Do Ho Suh, Rubbing/Loving Project: Seoul Home 2013-2022

Installation view at Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, Australia. Photography by Jessica Maurer. © Do Ho Suh

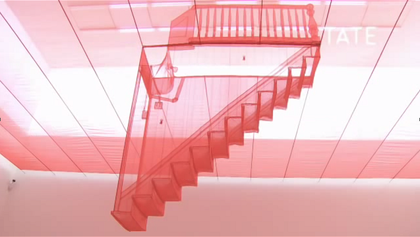

Find out more about our exhibition at Tate Modern

Do Ho Suh, Rubbing/Loving Project: Seoul Home 2013-2022

Installation view at Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, Australia. Photography by Jessica Maurer. © Do Ho Suh

You are in London, standing on the second floor of Tate Modern. Stepping across the threshold into Do Ho Suh’s exhibition, you will soon encounter buildings and spaces spanning multiple time periods. Many of these are places where Do Ho Suh has lived and worked and to which he repeatedly returns through his installations, videos and works on paper. Do Ho Suh: Walk the House surveys three decades of the artist’s practice across Seoul, New York and London – the three cities he has called ‘home’ at different points in his life.

‘Walk the house’ is a Korean expression Suh heard as a young boy from the carpenters who constructed his childhood home in Seoul. The building was a traditional Korean house known as a hanok. These buildings could be disassembled and reassembled in a new location – a process of literally ‘walking the house’. For Suh, the phrase describes how we carry multiple places with us across space and time. The relationship between architecture, the body and memory is central to Suh’s interests. As he says, ‘memory amalgamates in these spaces and memories shape our perceptions of them. Yet, they’re not stagnant. They’re not foreclosed environments in my work. They’re transportable, breathable and mutable’. To the artist, ‘home’ is not a fixed place or a simple idea. Instead, it evolves over time, and is continually redefined as we move through the world.

The exhibition’s open layout encourages moving back and forth through time and place, and meandering through the artworks. Suh’s works remind us that everything is connected – we exist within a network of relationships and experiences. As you explore, you may begin to wonder what spaces and times you carry with you as you move through the world. How does architecture shape and hold our memories? And in a world increasingly defined by movement – voluntary and involuntary – where and when is home?

When the viewer looks up, they encounter a void. As they look down ... the pedestal gives way to many figures – a mass of people that both support and resist its weight.

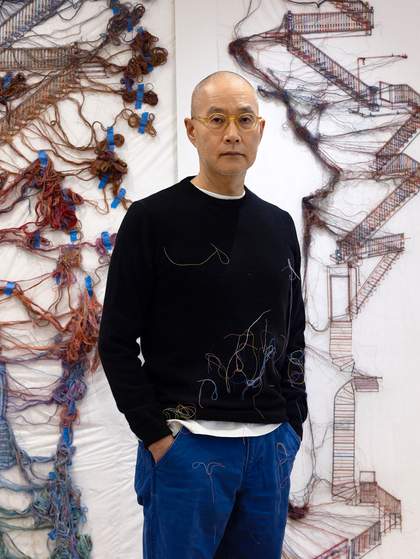

Do Ho Suh

Do Ho Suh’s work examines the relationship between architecture, space, the body and memory. Displayed outside the exhibition, two works in particular explore the tensions between individuality and collectivity, as well as habits of looking and perception.

Who Am We? is a wallpaper made of thousands of tiny portrait photographs. Suh collected the images in Seoul, over many years, from sources such as school yearbooks. The images were scanned and then reduced in size. From afar, the wallpaper looks like a pattern of dots, but closer inspection reveals details of distinct faces. The work explores the relationship and tension between the individual and the collective, and Suh’s interest in what he describes as ‘the minimum differential gap that lets me be what/who I am and not you, or anyone else’. Using wallpaper as a medium plays with the notion of blending in, as the work becomes part of the museum’s architecture.

Suh first made Public Figures 25 years ago. He has frequently returned to the idea of a public monument earned by individuals working together to unseat a celebration of patriarchal authority. After moving to the US, Suh became preoccupied with the role of the pedestal in public monuments and the official narratives it upholds. He says: ‘I was interested in the empty space below the male statues that populated civic squares.’ In Public Figures, the plinth is empty. Instead of commemorating a person or event, small figures below hold the plinth aloft together – a gesture of collective resilience and renewal.

Do Ho Suh was born in Seoul in 1962. He grew up in a hanok, a house based on an architectural style dating back to the early years of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910). Suh’s parents had the house built in the 1970s.

Suh began to explore the idea of home after leaving South Korea in 1991 and emigrating to the United States. Since then, his childhood home has repeatedly emerged through his work. For Rubbing/Loving: Seoul Home, Suh returned to the house and covered its entire exterior in paper. He then rubbed the surface with graphite, describing the technique as a ‘loving gesture’ that is mingled with a sense of loss. For Suh, rubbing is an act of witnessing as well as exploring ‘where memory actually resides’.

The style of Suh’s childhood home contrasted starkly with most of modern Seoul. The city was being rebuilt following liberation from Japan and destruction during the Korean War (1950-53). A rapidly growing population meant low buildings were replaced by high-rise blocks that were rebuilt constantly. The two video works displayed nearby – Robin Hood Gardens and Dong In Apartments – portray parallel stories of community housing blocks in London and Daegu, South Korea. Both had been constructed through similar development efforts during the 20th century and were later slated for demolition. Through the videos, Suh examines the stakes of destroying buildings that are both sites of architectural significance and homes to many individuals.

In the large-scale works on paper near the entrance, Suh explores how the past, present and future inform our understanding of home and identity. Bringing together different times and spaces, he moves away from opposing notions of ‘past’ or ‘present’, and ‘here’ or ‘there’. Instead, the drawings trace a cyclical rather than linear experience of time that has been important for Suh throughout his life. Many also playfully visualise how places, people and past selves are carried within us wherever we go.

Suh moved to the United States to continue his art studies at the Rhode Island School of Design, eventually settling in New York in 1997. During this period, he embraced two of his most central techniques – measuring and rubbing. Physically and mentally taxing, Suh uses these time-consuming processes to create portable versions of the places he has inhabited. Through measuring, he carefully documents a space, paying attention to its exact details. He describes how previously forgotten memories re-emerge as he retraces features by rubbing their surfaces through paper.

In the large-scale work Nest/s, Suh has stitched together a series of in-between spaces and rooms from buildings in Seoul, New York, London and Berlin. He connects them to form one continuous, impossible architecture. Suh calls these works, made using traditional Korean sewing techniques, ‘fabric architectures’. Through this process, Suh can pack up and transport spaces, fulfilling his desire to ‘fit my childhood home into a suitcase’. You are invited to enter the work and consider your own journeys through different spaces, types of architecture, cities and neighborhoods.

Suh’s practice also questions how memories can be embedded in spaces during political upheaval and censorship. His Rubbing/Loving: Company Housing of Gwangju Theater takes up the censored histories of those who experienced the Gwangju Uprising. This was a series of student-led protests which took place in Gwangju, South Korea in May 1980, and were suppressed by the authorities. By creating rubbings of the interior surfaces of buildings in Gwangju, Suh explores how they bear witness to violence and asks what memories they carry against the grain of official histories. Working with assistants, Suh’s collaborative process also becomes a moment of collective witnessing. He says: ‘It was not a performance, but there was a deeply moving sense of ritual, or commemoration, that came from doing things together.’

Do Ho Suh Nest/s 2024 Courtesy the artist, Lehmann Maupin New York, Seoul and London, and Victoria Miro. Creation supported by Genesis. © Do Ho Suh. Photo: Jeon Taeg Su

Early in his career, Suh often used drawing to develop ideas as well as work through technical issues with his installations. The works on paper displayed here date from 1999 to 2024 and trace how Suh’s approach has evolved over the years. They move from immersive to intimate, demonstrating Suh’s sensitivity to scale across his practice. You can see how he continually returns to places, forms and subjects as time passes.

Suh’s artworks have roots in his training in Korean ink painting, which he studied before emigrating to the United States. This practice traditionally uses paper as its base. Suh plays with the principles of ink painting, describing his interest in the artist’s surrendering of control as ink marks expand through the absorbent paper fibres. He initially used ink, watercolour and pencil for his paper-based works, but for more than a decade he has developed his own experimental techniques. In Staircase, shown nearby on the right, Suh has worked with threads embroidered on gelatine tissue paper to collapse a three-dimensional form onto a two-dimensional plane. Like the fabric architectures, which can be packed away like clothing, this process allows Suh to create portable versions of meaningful spaces.

The constant return to spaces, or the feeling of being ‘haunted’ by them, is visualised in the work Home Within Home, on the left. Suh uses 3D printing techniques to merge two buildings in which he has previously lived, one in South Korea and the other a house of rented apartments in the US. This process blurs the distinctions between the buildings, which are at a shrunken, more intimate scale. Suh has talked about the cultural collisions and language barriers he experienced on moving from South Korea to the US. His work explores how, as we move through the world, we constantly reconsider who we are, through contact with the places in which we find ourselves.

There is a deliberate tension in Suh’s work between precision and impression, reminiscing and forgetting, the act of preserving and moving on. His fabric architectures and rubbings evoke the places he has inhabited, but the materials he makes them from resist exact replication. Fabric yields, minutely altering the shape of the buildings it brings into view. Paper cannot perfectly cling to the contours of every detail as Suh rubs over them. He explains: ‘It’s more about capturing enough visual and physical information to evoke a sense of the space as I experienced it.’

Before Suh left New York for London, he rubbed the interiors of the apartment he had rented for two decades, creating Rubbing/Loving Project: Unit 2, 348 West 22nd Street, New York, NY 10011, USA. He moved to London in 2016, and portrays his home in this city in the fabric architecture Perfect Home: London, Horsham, New York, Berlin, Providence, Seoul. The work is based on a 1:1 scale outline of the interior of Suh’s London home, but accumulated within it are fixtures and fittings from multiple places he and his family have lived in over the years. He locates light switches, doorknobs and plug sockets at the positions and heights they would be found in their original geographic location. Suh evokes the almost unconscious rituals that create a sense of familiarity such as opening a door or switching on a light. He has compared the disorienting effects of adjusting to these geographic differences to the physical experience of jetlag.

Suh refers to the fixtures in these two works as ‘specimens’. In the wall-based Rubbing/Loving Project: Unit 2, 348 West 22nd Street, New York, NY 10011, USA, they are still in their original packing, evoking a display case in a natural history museum. In his acts of ‘preserving’ spaces and their memories, Suh describes being flooded with both recollections and apparitions: ‘overtaken by the meditative process of rubbing … I felt as if I was hallucinating.’ The works also remind us that our own memories of any time and place are often partial and fragmentary.

It’s a constantly evolving project, and by its nature unresolved. Borders move or close, global warming causes climate change, families and personal connections grow or shift, people move – whether voluntarily or because they are forced. The bridge has many possible outcomes and manifestations. I don’t have a fixed concept of home – it will continue to evolve.

Do Ho Suh

Bridge Project is a speculative exploration by Suh, begun in 1999, imagining his ‘perfect home’ at the centre of a bridge connecting the three key cities in his life. The notion of a ‘perfect home’ is a provocation – an impossible idea. In Phase 1, Suh proposes four speculative bridge designs that span the North Pacific Ocean, linking Seoul to New York. Phase 2 includes London, where he now lives. Measuring the distances between these three locations, Suh found their midpoint to lie in the Arctic Ocean.

Suh invites us to consider how art can imagine new worlds, even if some will remain unrealised. At the same time, he grapples with real-world social, political and ecological issues. Suh’s ‘perfect home’ would be located over 700 kilometres from the nearest Arctic Ocean coastline. The exact site is under no country’s jurisdiction but has been subject to competing claims from Norway, Canada, Denmark, Russia and the US. The nearest lands are home to the Indigenous Chukchi of the Chukotka Peninsula and the Iñupiat of Alaska. The project raises many questions. Whose land would the bridge infringe upon? What would the environmental impact be? With so many homes under threat, surely the idea of a ‘perfect home’ is contradictory ?

Suh has worked with specialists from architecture, engineering, industrial and clothing design, philosophy, anthropology and biology, to interrogate these issues. The project is also informed by Suh’s own migration experiences and reflections on globalisation. While the work has various outcomes – designs, maps, animations and survival suits – at its core it exists in an imaginary space.

Artist page for Do Ho Suh (born 1962)

Do Ho Suh’s monumental fabric architectures, life-sized works on paper and complex drawings made with multicoloured thread powerfully explore ideas of belonging and connection. Ahead of Suh’s major survey show at Tate Modern, artist Janice Kerbel speaks to him about memory, collaboration and his ongoing quest for the perfect home

A gauzy red staircase floats high up in a gallery at Tate Modern