Was ‘pop art’ a term used by yourself or colleagues or was there a different terminology that referred to a new figurative art movement in the 1960s and early 1970s?

I would prefer to call it ‘nouvelle figuration’ as, at the time, it referred to Latin-American problems and especially to Brazil, a country that was undergoing political restraints due to the military dictatorship that governed. The ‘nouvelle figuration’ or ‘new objectivity’ used a language that was similar to the one used by both the mass media and the messages conveyed by the urban background. We transformed their meanings and suggested images that questioned the social conditions we were going through. We responded to the changes that happened in the arts and especially to the changes that occurred in society and to the new line of thought of the young people. The artworks reached beyond the borders of the fine arts and were exhibited in alternative venues such as public spaces, theatres and trade union headquarters rather than museums and art galleries. We were interested in communicating directly with the public and were eager to follow their responses to them.

Did you ever consider yourself (now or in the past) a pop artist?

The source of the language used in my work, appropriated from the mass media and the urban signals, created a visual similarity with international pop art. My work focused on the social and historical conditions we were going through in our country [Brazil] and my themes referred to our major concerns at the time. I was aware of the huge difference between the works of American artists, who were engaged in stressing the consumerism in their milieu and with the glamorisation of their images, and goods on the supermarket shelves. The choice of alternative spaces to show our works, and the possibility of silkscreen reproductions on a massive scale, enlarged and created a new awareness in an ample and diversified population. From the point of view of image consumerism we established a close link with the proposals of pop art.

Did your work engage with current events in the 1960s and early 1970s?

Most part of the cultural output of the 1960s and early 1970s was intended to denounce the repression and oppression that we suffered under the military dictatorship. At the time I was young and was studying architecture at the University of São Paulo. I also participated in the students’ movement and in clandestine organisations. My work reflected the meeting between art and life. I had a routine that was similar to that of journalists: I used to do iconographic research using pictures I had taken as well as material that was published in the media. Their meaning was then transformed and incorporated to painters’ language.

Claudio Tozzi

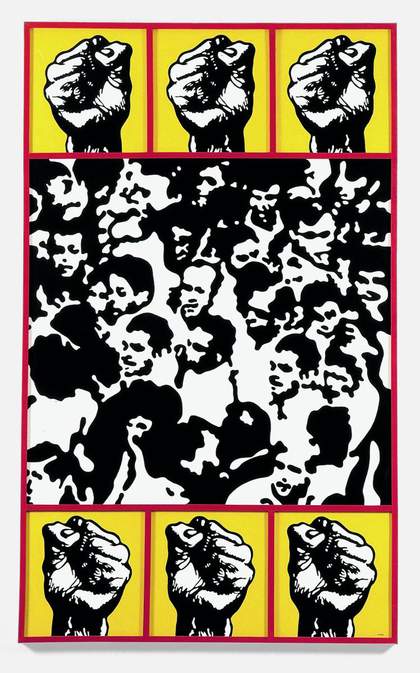

Multitude 1968

Museu de Arte Moderna, São Paulo, Brasil

© Claudio Tozzi

How did you choose the subject matter for your work included in The World Goes Pop?

The images used in the series entitled Crowds were based on photos I had taken and also on an iconographic research I had made based in magazines and newspapers published at the time. There was an interval between the event recorded and the work. The photographic images were treated in specialised labs to amplify the lighting and stress the contrasts. Then, the images were reduced to their main elements through the use of drawing on translucent tracing paper, changing their original scale and reducing the relationship between light and dark so as to convey emotion in the photos by altering their profiles, and through the treatment of the tracings. The working up of the images in the studio led to a specific code which reflected the social and political moment at the same time that it established a distance between reality and the painted image. We started with a spontaneous generation of an image in a photograph and achieved a chosen and predetermined goal in the painting.

Where did you get your imagery from (what, if any, sources did you use)?

The subjects I focused on in my work were suggested by newspaper articles and photos and on daily life: demonstrations, students being arrested, repression, sexual freedom, guerillas, Che Guevara. The use of images based in mass media and on the urban environment reflected the Duchampian concept of appropriation of images. The original meaning of the image was modified and adapted to the circumstances and were used on a wide range of supports that included the traditional canvas as well as experiments with photocopies, screenscreens, Super 8 films and body language which stressed the message. Our main concern was interacting with the public.

Were you aware of pop art in other parts of the world?

Through publications, books, magazines, conferences and debates that took place in the History department of the Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de São Paulo (College of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of São Paulo) I acquired a wide range of knowledge of the new figuration and pop art in different countries. At the São Paulo Biennial there was a pop art exhibition room, which showed works by almost all of the American artists of the time. Some Latin American institutions carried out research and organised exhibitions of the new figuration artworks.

Was commercial art an influence on your work or the way in which it was made?

My work in the 1960s moved away from traditional easel painting. I worked on a horizontal surface and used as a support industrially produced agglomerated plates. The ink I used was the same as that commonly used to make traffic signs and urban advertisements. I started to work with Liquitex, an acrylic resin widely used by pop artists, which had characteristics similar to those used in publicity. Some processes such as silkscreen paved the way to the appropriation of photographic images and their coupling to the painting. The traditional processes of printing using typography and offset allowed the creation of photolithograph with different graphical reticules that were then incorporated into the work.

Was there a feeling at the time that you doing something important and new, making a change…?

These works embodied an in-depth transformation of the traditional language of painting. One of the characteristics of the nouvelle figuration and of pop art in Brazil was the use of specific aspects of the political and social conditions that prevailed during the military dictatorship. The repression and oppression under which we lived conflicted with the feeling of hope in the construction of a fairer and more independent country. Painting played a role in these hopes. Its subjects included references to situations which were pregnant with denunciations and protests about the daily events that were taking place in Brazil. Similarly painting took as its theme the new behaviour of young people contrasting with the way they were expected to behave. The works were exhibited in alternative spaces rather than museums and galleries, which allowed closer contact with the public.

Was there an audience for the work at the time – and if so what was their reaction to it?

The public interested in the fine arts was very restricted at the time. In order to enlarge it we used alternative venues to divulge our work. Silkscreen was widely used to reproduce the images without attributing numbers to the series as is used today and thus keep them far from commercial purposes. We produced images of popular idols on paper, fabrics, T-shirts and other items that transgressed the traditional ones. We organised an exhibition entitled Flags in a public square, which drew a large number of people. Another exhibition focused on stamps with images that were chosen by the audience. Spectators stamped the chosen image on paper and took them home. These were actions that aimed to make people connect and get more used to artworks.

Looking back at these works, what you do think about them now?

It was an avant-garde language in fine art production of the 1960s. The themes were a response to daily life events, with the social criticism and the struggle against the military dictatorship. These characteristics paved the way for their acceptance by the art reviewers and the wider public. We were also very much concerned with the formal structure of the works. Each image was transferred to canvas after an in-depth study of colour, shape and dimension so as to create a dialogue, a relationship between the forms that is the core of the specific universe of painting. Their structure followed a constructive rigour which is still present in my work.

September 2015