Zazi II, ISGM, Boston, 2019

Zanele Muholi (they/them) is a South African visual activist whose work tells the stories of Black LGBTQIA+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Agender, Asexual) lives in South Africa and beyond. Through photography, they raise awareness of injustices and create positive visual histories for under- and mis-represented communities. Muholi also turns the camera on themself, making self-portraits that address the politics of race and the power of the Black gaze. This exhibition charts Muholi’s work from their emergence as an activist in the early 2000s to the present day.

Born in 1972, Muholi grew up during the apartheid regime, a political and social system of racial segregation underpinned by white minority rule. This regime also upheld injustice and discrimination based on gender and sexuality. Apartheid was officially abolished in 1994. Although South Africa’s 1996 constitution was the first in the world to outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation, the LGBTQIA+ community remains a target for prejudice, hate crimes and violence.

Through their work, Muholi speaks to injustice and advocates for change, while also celebrating moments of love and joy. In these images, they reveal the power of togetherness and healing which lies at the heart of their community. Since 2020, Muholi has expanded their portraiture practice into sculpture, reckoning with the relationship between public and private spheres. Several of their new bronze sculptures feature throughout this exhibition.

Room 1

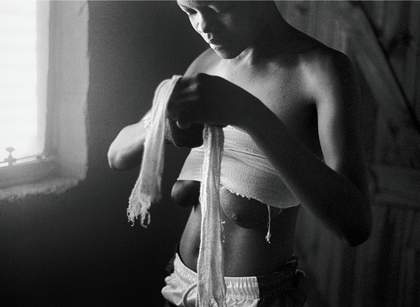

Zanele Muholi, ID Crisis, 2003 © Zanele Muholi Courtesy of the Artist and Yancey Richardson, New York

Only Half The Picture

Between 2002 and 2006, Muholi created their first series of photographs, Only Half the Picture. This project was part of their work with the Forum for the Empowerment of Women, which Muholi co-founded in 2002. It documents survivors of hate crimes living across South Africa and its townships. During apartheid, the government established townships as residential areas for those they had evicted from places designated as ‘white only’. Muholi presents the people they photograph – their participants – with compassion, dignity and courage in the face of ongoing discrimination. The series also includes images of intimacy, expanding the narrative beyond victimhood. Muholi reveals the pain, love and defiance that exist within the Black LGBTQIA+ community in South Africa.

Room 2

Zanele Muholi Lerato Dumse, Syracuse, New York Upstate 2015 © Zanele Muholi Courtesy of the Artist and Yancey Richardson, New York

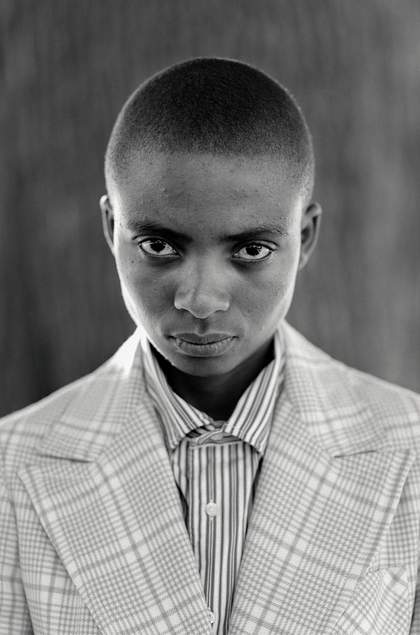

Faces and Phases

It is important to mark, map and preserve our mo(ve)ments through visual histories for reference and posterity so that future generations will note that we were here.

Zanele Muholi

Muholi began their ongoing series Faces and Phases in 2006. The project currently totals over 600 works. As a collective portrait, it celebrates, commemorates and archives the lives of Black lesbians, transgender and gender non-conforming people.

Many of these portraits are the result of long and sustained relationships and collaboration. Muholi often returns to photograph the same person over time. In the title, ‘Faces’ refers to the person being photographed. ‘Phases’ signifies a transition from one stage of sexuality or gender expression and identity to another. It also marks the changes in the participants’ daily lives, including ageing, education, work and marriage. The gaps in the grid indicate individuals that are no longer present in the project or a portrait yet to be taken.

Faces and Phases forms a living archive, visualising Muholi’s belief that ‘we express our gendered, racialised and classed selves in rich and diverse ways’.

Busi Sigasa

Remebmer Me When I’m Gone

For I …

Wrote stories for the nations to read

Stood without fear and told my story

I smiled and greeted without judging

I influenced positive living to the sick

I planted seeds of hope to the hopeless

I groomed and grew

the younger ones whose parents died

I created artistic designs with my hands

I crafted and drew beautiful pictures

I installed education

l reasoned to some

I represented the minority to the majority

I made nations aware

I wronged some and made some happy

I survived against odds

I swallowed my medication even as hard as it was sometimes

I did so to remain strong and true

I lived my life regardless of my status

I fought for women to be taken into serious consideration

by our government

I wrote and said ‘my’ spoken word I fought and showed many that there’s nothing

wrong with being diabetic, epileptic and HIV

I represented many of the HIV infected lesbian sisters

I told the truth never mind the judgements

I lived and I’m still living

I loved and prayed to my GOD

I prayed without hesitation, for

I believe/d I was a big sister to my younger sisters

I listened to my mother’s teachings

I became friends with father

I’D DIE FOR MY FAMILY,

I LOVED THEM SO!

I captured moments with my camera

I brought forth what was unseen to the nations

through the power of image, pen and paper

I struggled to make it live

I was taken for a ride by some whom

I thought were friends

I showed my rapist how strong I was regardless that he poisoned my blood with his HIV

I believed and prayed

I stood low and respected all regardless of their age,

colour and size

I say along with others I had a unique voice

I had a message to deliver and a vision to see

I tried,

I fell and I never succeeded sometimes

I was patient while to some

I was strange

I was loved by some and was hated by some,

STILL I did my thing

I loved and appreciated beautiful women

I loved them more than life itself

Some would say …

I am full of shit!

but spiritually I was full

I was fed with GOD’s glory that’s why I praised HIM

I praised HIM more than I praised friends

I am my mother’s daughter

I made history and marked historical books of this world

SO … REMEMBER ME WHEN I’M GONE!

FOR ... without no doubt

I am in peace with my maker and creator.

Room 3

Zanele Muholi, Katlego Mashiloane and Nosipho Lavuta, Ext. 2, Lakeside, Johannesburg, 2007 © Zanele Muholi Courtesy of the Artist and Yancey Richardson, New York

Being

The portraits in Muholi’s series Being (2006 – ongoing) capture moments of intimacy between couples, as well as their daily lives and routines. Muholi addresses the misconception that queer life is ‘unAfrican’ or non-existent. This falsehood emerged in part from the belief that same-sex orientation was a colonial import to Africa. Same-sex relationships and gender fluidity have always existed in Africa. Each couple is shown in the private spaces they share. Muholi explains how ‘lovers and friends consented to participate in the project, willing to bare and express their love for each other’. Commenting on this series, they say, ‘my photography is never about lesbian nudity. It is about portraits of lesbians who happen to be in the nude’.

The sculpture Ncinda depicts the full anatomy of the clitoris. Referencing intimate pleasure, it also breaks taboos often associated with this organ.

Since slavery and colonialism, images of us African women have been used to reproduce heterosexuality and white patriarchy, and these systems of power have so organised our everyday lives that it is difficult to visualise ourselves as we actually are in our respective communities. Moreover, the images we see rely on binaries that were long prescribed for us (heterosexual/ homosexual, male/female, African/unAfrican). From birth on, we are taught to internalise their existences, sometimes forgetting that if bodies are connected, connecting, the sensuousness goes beyond simplistic understandings of gender and sexuality.

Zanele Muholi

Room 4

Miss D’vine I, Yeoville, Johannesburg, 2007

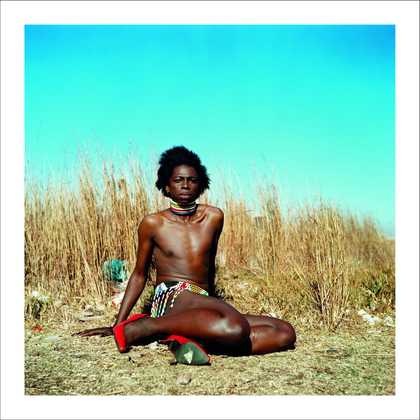

Queering Public Space

Collaborating with Black LGBTQIA+ participants and photographing them in public spaces is an important part of Muholi’s visual activism. This room features portraits of transgender women, gay men and gender non-conforming people photographed in public places.

Several of the locations have important historical meaning in South Africa. Muholi captured some images at Constitution Hill, the seat of the Constitutional Court of South Africa. It is a key place in relation to the country’s progression towards democracy. They photographed other participants on beaches. Segregated during apartheid, beaches are potent symbols of how racial segregation affected every aspect of life. Participants are often shown on Durban Beach, close to Muholi’s birthplace of Umlazi. Choosing to photograph participants in colour is a way for Muholi to bring the work closer to reality and to root them in the present day.

Muholi states, ‘we’re “queering” the space in order for us to access the space. We transition within the space in order to make sure that the Black trans bodies are part of this as well. We owe it to ourselves.’

Room 5

Sazi Jali, Durban, 2020

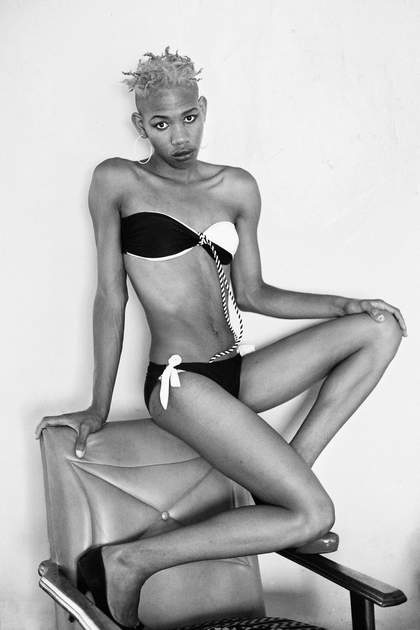

Brave Beauties

Brave Beauties (2014 – ongoing) is a series of portraits of trans women, gender non-conforming and non-binary people, inspired by fashion magazine covers. Many of the participants in this series are beauty pageant contestants. Queer beauty pageants offer a space of resistance for the Black LGBTQIA+ community in South Africa. They are a place where people can realise and express their beauty outside heteronormative and white supremacist norms. Muholi won second place in such a pageant in 1997. They have commented that these participants ‘enter beauty pageants to change mindsets in the communities they live in, the same communities where they are most likely to be harassed, or worse’.

These images aim to challenge queerphobic and transphobic stereotypes and stigmas in the fashion industry. Muholi has questioned whether ‘South Africa, as a democratic country, would have an image of a trans woman on the cover of a magazine’. As with all Muholi’s images, the portraits are created through a collaborative process. Muholi and the participant determine the location, clothing and pose together, focusing on producing images that are empowering for both the participant and the audience.

Room 6

Still from video interview with Zama Shange

Courtesy of the artist

Interviewer, Transcription, Videography & Sound: Thobeka Bhengu

Sharing Stories

From their earliest days as an activist, Muholi sought to record the first-hand testimonies and experiences of Black LGBTQIA+ people. Giving participants a platform to tell their own story, in their own words, has been an enduring goal. Muholi has said, ‘each and every person in the photos has a story to tell but many of us come from spaces in which most Black people never had that opportunity. If they had it at all, their voices were told by other people. Nobody can tell our story better than ourselves.’

In this room, participants share stories of their lives and experiences as members of the LGBTQIA+ community in South Africa. Some feature in the Faces and Phases series in this exhibition. Muholi’s collaborators conducted and produced the interviews.

Some testimonies do not use Muholi’s pronouns: they/them.

Room 7

Zanele Muholi, Jula I, Wild Coast 2020, © Zanele Muholi Courtesy of the Artist and Yancey Richardson, New York

Somnyama Ngonyama

In Somnyama Ngonyama (2012 – ongoing), Muholi turns the camera on themself to explore the politics of race and representation. The portraits are taken in different locations around the world. They are made using materials and objects that Muholi sources from their surroundings.

The images are acts of resistance, referring to personal stories, colonial and apartheid histories of exclusion and displacement, as well as ongoing racism. They question racist violence and harmful representations of Black people. Muholi’s aim is to draw out these histories in order to educate people about them and to facilitate the processing of these traumas both personally and collectively.

Muholi considers how the gaze is constructed in their photographs. In some images, they look away. In others, they stare the camera down, asking what it means for ‘a Black person to look back’. When exhibited together, the portraits surround the viewer with a network of gazes. Muholi increases the contrast of the images in this series, which has the effect of darkening their skin tone. ‘I’m reclaiming my Blackness, which I feel is continuously performed by the privileged other.’

Somnyama Ngonyama is also a homage to the plurality and fluidity of the self. For Muholi, their use of the pronouns they/them goes beyond gender identity. It acknowledges their ancestors and the many facets of their identity: ‘There are those who came before me who make me.’

Room 8

Lerato Dumse, Muntu Masombuka’s Funeral, Johannesburg, 2014

Collectivity

Collectivity lies at the heart of Muholi’s work. Many of Muholi’s large network of collaborators are members of their collective, Inkanyiso. This means ‘light’ in isiZulu, Muholi’s first language and one of 11 official languages in South Africa. Inkanyiso’s mission is to ‘Produce, educate and disseminate information to many audiences, especially those who are often marginalised or sensationalised by the mainstream media’. ‘Queer Activism = Queer Media’ is the collective’s motto.

In 2022, Muholi opened the Muholi Art Institute in Cape Town. This mobile art organisation supports young and upcoming South African visual artists with spaces for studios, exhibitions and events. Posters publicising talks by inspirational speakers that the institute organised are shown in this room.

Self-organisation, mentorship and skill sharing are central to Muholi’s collaborative practice. This room features images that were made collaboratively. Whether documenting public events such as Pride marches and protests or private events such as marriages and funerals, these images form an ever-expanding visual archive. By recording the existence of the Black LGBTQIA+ community, they resist erasure. The images reveal the power of collective voices in protests and social justice movements. They also celebrate the moments of love, care and resistance that are at the centre of Muholi’s community and activist work.

Room 9

In this section, there are several images of weddings and funerals. Religion, spirituality and the Christian church play central roles for many of the individuals featured in this exhibition. The services shown here are often held by pastors from churches founded specifically for and/or by LGBTQIA+ people in South Africa. Organisations such as the Victory Ministries Church International in Durban offer a safe space for worship for individuals who may have been rejected by family, friends or mainstream churches because of their identity.