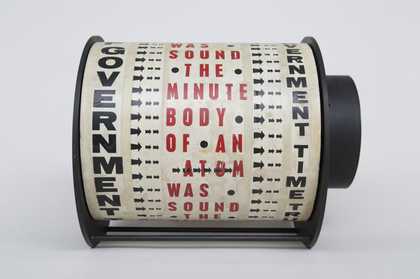

Liliane Lijn, Get Rid of Government Time 1962. Stephen Weiss, London. © DACS/Artimages, London.

Introduction

‘I want to feel alive in my work. I want it to breathe. I want its surface to be as skin, translucent, porous, emitting the fine moist heat of the living’ – Liliane Lijn

Liliane Lijn (born 1939, New York) has been working at the intersection of art, poetry and science for over six decades. This exhibition explores three key themes that span Lijn’s career: kinetic art – initially through motorisation and optical effects; light and energy – giving visible form to immaterial and invisible forces; and feminism and the body – challenging dominant ideas of the feminine in art and technology. Arise Alive is the most comprehensive survey of the artist’s work to date.

Lijn spent her early career in Paris, New York and Athens before settling in London in 1966. In her early works, she experimented with the effects of light and shadow by cutting and drilling into transparent plastic. She then began to incorporate moving light sources, electric motors, lenses, text and sound, becoming one of the first women artists to make kinetic (moving) sculptures.

Lijn explores relationships between the material and immaterial, light and energy. She uses found objects and industrially produced elements including plastic, aluminium, copper wire, and glass prisms, but also natural materials such as feathers and stone, sometimes merging these within one form.

Her multi-faceted work reflects her longstanding interest in Asian philosophies, spirituality, mythology, scientific innovation, and feminist thought. Since the late 1970s, Lijn has increasingly focused on notions of the female, as expressed through drawings, sculptures and her own writings. Her search for a new female iconography culminates in her Cosmic Dramas, large-scale installations whose figures seem part-machine, part-goddess.

Liliane Lijn, Headborn 1986. Tate: Purchased with funds provided by the Denise Coates Foundation on the occasion of the 2018 centenary of women gaining the right to vote in Britain 2019. © Liliane Lijn / DACS 2025. Photograph: Tate

Paris

Born and raised in New York City, Liliane Lijn moved to Paris in 1958. She initially studied archaeology at the Sorbonne and art history at the École du Louvre, but soon interrupted her studies to focus on painting. Paris in the late 1950s was a vibrant artistic centre. Lijn’s time there was one of enormous creativity and adventure, though there were few other women in the circles she moved in.

Lijn became associated with surrealism, an artistic and literary movement exploring the unconscious mind. The influence of surrealists she encountered, including André Breton and Max Ernst, can be seen in her early drawings in this room. She also looked to a range of other sources, from the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch to Chinese scrolls and Zen Buddhism. Even at this early stage, her interests spanned art, literature, philosophy and science, and in Paris she developed a way of seeing the world that would continue to define her practice going forward.

Light and Movement

In Paris and New York in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Lijn started working with plastics. First using melted polymer-based ski wax, she soon began to cut or drill into plastic blocks. These works produce optical illusions of mass through light and shadow, which Lijn terms ‘an architecture of the void’. She later introduced moving lights shining through plastic droplets applied using hypodermic needles. Lijn wanted to suggest photons, the tiny electromagnetic particles that make up light.

This interest in science – especially astronomy and quantum physics – is reflected in her earliest rotating kinetic sculptures made in Paris, Athens and London in the 1960s. In parallel, she began exploring both the cut-up narrative techniques used by Beat poets and concrete poetry, where meaning comes from the graphic arrangement of words. Her Poem Machines introduce text onto moving surfaces, blurring boundaries between language and form. Using lines from her own poems or those by friends and other writers, Lijn wanted to ‘visualise the energy of sound’.

Liliane Lijn, Double Drilling, Inner Space, Yellow Drilling 1961. Courtesy Liliane Lijn and Sylvia Kouvali, London / Piraeus. Exhibition view: Liliane Lijn. Arise Alive, mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, November 15, 2024 – May 4, 2025 Photo: Georg Petermichl / mumok.

Koans

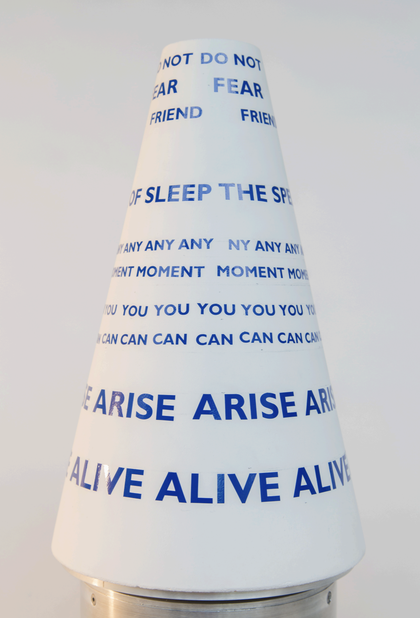

From 1965, Lijn started making cone-shaped kinetic sculptures. These take inspiration from the Greek goddess Hestia who is symbolised by a conic mound of white ash. Lijn titles them Koans, which in Zen Buddhism refer to paradoxical statements or riddles used for meditation. Lijn’s earliest Koans focused on poetry and movement, continuing the ideas of her Poem Machines.

Lijn started to make large-scale Koans in 1969, many of which she remade from 2006–8, including Lost Koan (2006), shown here. With these works, she wanted to create ‘a paradox by dissecting the cone form into elliptical sections and restoring it with planes of fluorescent acrylic that appear on its surface as luminous lines dissolving the materiality of the solid cone’.

Liliane Lijn, Arise Alive 1965. Catherine Petitgas Collection © DACS/Artimages, London. Photograph: Richard Wilding

Drawings and Writings

Drawing has been central to Lijn’s work throughout her career, from her earliest sketches in the late 1950s to studies made for her large-scale Cosmic Dramas in the 1980s. Lijn: ‘I don’t think about what I will draw; I just let whatever medium I use take me somewhere. Drawing is like going fishing in my subconscious.’

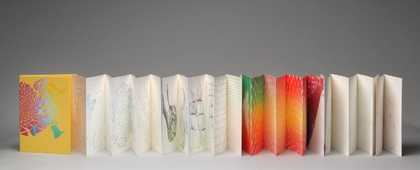

In the 1970s, Lijn worked on numerous drawing series alongside her sculptural practice. These reflect the scientific and philosophical ideas that underpin her work. She also wrote extensively, and both practices were combined in her 1983 illustrated prose poem Crossing Map. A hybrid of science fiction, autobiography and eco-feminist manifesto, it marked a new artistic direction for Lijn as she began to focus on explicitly feminist themes.

Liliane Lijn, Crossing Map 1983–2002. Tate: Purchased 2019. © Liliane Lijn / DACS 2025.

Liquid Reflections and Denslens

Liquid Reflections (1968) were Lijn’s first and most complex works with water and light. Inspired by her interest in astronomy and the physics of light, they were the outcome of five years of experimental work with acrylic polymers, fire, lenses, prisms, light and finally water. The movement of the balls across the discs is governed by laws of momentum, centrifugal force and the pull of gravity induced by the concave shape of the discs. The balls also act as moving magnifying lenses, ‘bringing to life now one area of the disc, now another, with a strange lunar landscape of reflections and shadows’. These works are Lijn’s attempt to contemplate the universe on an intimate scale.

Similarly, Denslens (1974–5) uses a lens to magnify and diffract light reflecting off a wire-wrapped rotating cylinder. When experienced from a certain viewpoint, the motion creates a vibrant spectrum of colours. This work reflects her interest in the Buddhist philosopher D. T. Suzuki, who writes: ‘Buddhists have conceived an object as an event and not a thing or substance.’ Denslens becomes an event governed by space and time, as the observer’s position unlocks the effect and the colours change with each moment.

Liliane Lijn, Liquid Reflections 1968. Courtesy Liliane Lijn and Sylvia Kouvali, London / Piraeus. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024. Photograph: Maximilian Geuter

Conjunctions of Opposites

In the 1980s, Lijn began making her Cosmic Dramas. These works combine technology, science fiction, mythology and feminism.

Taking its title from an ancient nymph goddess Robert Graves describes in his book The Greek Myths (1955), Lady of the Wild Things (1983) is imagined as a protector of nature. The figure’s head is a periscope prism originally made for a military tank, and her wings light up in response to sound. Her counterpart, Woman of War (1986), is based on a 1959 painting Lijn made of a bird goddess she envisioned rising from the clouds at sunset. The sculpture opens her wings and sings with a synthesised version of Lijn’s voice: ‘I’m the Image of Woman / The Image of She / A Woman of War.’

These two works were first brought together at the Venice Biennale in 1986 under the title Conjunction of Opposites. Woman of War sings to Lady of the Wild Things, who responds by transforming sound into light. A red laser connects these ‘goddesses of the space age’, shining through a cloud of artificial mist.

Liliane Lijn, Conjunction of Opposites: Woman of War and Lady of the Wild Things 1986. Courtesy the artist and Sylvia Kouvali, London / Piraeus. © Liliane Lijn / DACS 2025. Photography: Thierry Bal.

Prisms and Female Figures

In the 1970s and 1980s, Lijn regularly introduced prisms into her sculptures. This continued her interest in optical effects and the relationship between light and shadow. Prisms refract light into its constituent colours, and have many scientific applications. Lijn became interested in their use in spectroscopy to reveal what stars are made of, making invisible matter visible: ‘I do not wish to use prisms to see in a particular preplanned way, but to allow the prism to show me the unexpected’.

Lijn used prisms as heads for her sculptural series Female Figures, her earliest loosely human-shaped works. They portray powerful female figures, each with their own distinct character. Lijn based them on ideas drawn from mythology, literature, philosophy and science. Aiming to create ‘a different image of the feminine’, the figures challenge dominant ideas around femininity.

Liliane Lijn, Queen of Hearts, Queen of Diamonds 1980. Courtesy Liliane Lijn and Sylvia Kouvali, London / Piraeus. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024. Photograph: Maximilian Geuter

Electric Bride

The work in the next room is one of Lijn’s Cosmic Dramas. Electric Bride (1989) was inspired by a visit to a power station. Lijn perceived the huge transformers as being in cages, ‘with their outstretched arms sparking electricity into the darkness appearing to me as icons of the great goddess of our time’. While machines have often been associated with masculinity, this work gives a feminised reading of technology.

Lijn also drew on mythology, combining references to the Gorgon monster Medusa of Greek mythology and Inanna, ancient Mesopotamian goddess of love, war and fertility. The ‘bride’ has a flashing glass head, 16 arms stacked with mica, and is connected to a steel mesh enclosure with red-hot wires. She whispers a poem in Japanese that Lijn describes as ‘an encounter with mortality and a giving in to its overwhelming power only to emerge as light’.

Liliane Lijn, Electric Bride, 1989. Tate Collection. Courtesy Liliane Lijn and Sylvia Kouvali, London / Piraeus © DACS/Artimages, London. Photograph Thierry Bal.

Bride's Song

I am the bride.

Whirling wind woman.

I am she who goes willingly to darkness.

I am the bride.

Fragrant moon flower.

Look upon me to give to the world.

I am lady of the nether region.

White bride and mistress of death.

My fruit is dark and pitted.

I spin a web of fire.

Shrouded in veils

I am the many layered one.

I am the bride.

I am she who goes willingly to darkness

Transforming it to light.

Translated into Japanese and whispered by Japanese pop singer Takako Shirai for the installation Electric Bride, first exhibited in 1989 in Nagoya, Japan at the first Artec Biennale. Subsequently exhibited at Les Artists et La Lumiere at Le Manege, Reims in 1991, and at Andata e Ritorno at Palazzo Bonacossi, Ferrara in 2004.

Portraits

The 1980s was a period marked by significant upheaval in Lijn’s life. Focusing on self-reflection and aiming to capture the essence of the female psyche, she developed series including Inner Portraits and Fierce Archetypes. Lijn made these semi-abstract drawings using imagination and movement rather than planned composition. They are titled after legendary women or female archetypes such as ‘bride’ and ‘mother’.

Many of Lijn’s works from this period focus specifically on heads. In her Net Heads drawings, heads are formed using nets or meshes, which for Lijn relate to veils and webs. These studies led to her Torn Heads, glass forms that appear ripped open. Lijn writes: ‘My idea was that it was torn, that my head was torn apart but also – it was like a wound – and also it was like hair.’

Liliane Lijn: Arise Alive is organised by Haus der Kunst München and mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, in collaboration with Tate St Ives.

Liliane Lijn, Flower Bride 1987. Courtesy Liliane Lijn and Sylvia Kouvali, London / Piraeus. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024. Photograph: Maximilian Geuter