Many, perhaps most, of the great art writers are famous enough that enterprising young scholars know of them. A few, however, attract only small readerships, and so the story of their discovery by such students deserves recounting. In 1968, when I was a graduate student in philosophy at Columbia University taking an interest in aesthetics, I was very lucky – Richard Wollheim was a visiting professor and his Art and its Objects, which had just been published, became my introduction to the field. 1 The book was dedicated to Adrian Stokes and in the bibliography Wollheim wrote:

There is little in the literature of aesthetics that can be recommended in an unqualified way. I can enumerate the works that I have found most valuable or suggestive: they are Kant’s Critique of Judgment, the Introduction to Hegel’s Philosophy of Fine Art, Alain’s Système des Beaux-Arts, Ernst Gombrich’s Art and Illusion and Meditations on a Hobby Horse, and the essays of Adrian Stokes.2

The other writers, all famous, were known to me, but who was Adrian Stokes? It took me some time to answer that question. This was how I learned about him.

At that time, when I first read Stokes, I did not know anything about art history. Nor had I seen most of the art he described. My concern, as a philosopher, was to understand and critique his aesthetic theory. And so I did my doctoral thesis (1972) on Stokes, on Gombrich and on Nelson Goodman’s Languages of Art 1968, which then was a very influential new treatise on aesthetic theory. Gombrich and Goodman dispute the nature of perspective as convention; and Gombrich and Stokes offer very different psychoanalytic interpretations of visual art. But since it was impossible to synthesise the claims of these three very diverse writers, my thesis was not really a success. What is Stokes’s place within the history of aesthetics and art history? That question was not easy for me to answer. At Columbia I took one art history class, a survey discussion of the origins of abstraction by Meyer Schapiro, who by then was very renowned; his large class was very crowded. Schapiro, famously widely read, had of course studied Stokes. When I asked him for advice about my thesis, he gave me a clever one-liner: ‘Stokes stands to art history as astrology stands to astronomy’. Howard Hibbard, an eminent art historian who had a personal interest in psychoanalysis, was on my thesis committee. He supported my thesis, though politely indicated that he had no interest in Stokes.

How you read and evaluate Stokes’s writings depends upon where you are coming from. ‘My’ Stokes, now as in 1968, is very much a philosopher’s Stokes. No doubt it took me a long time to understand some elementary things, which an art historian would have grasped quickly. But it is also true that had I studied art history in graduate school then, very likely – so Schapiro’s statement and Hibbard’s response to my thesis suggest – I would not have seriously read Stokes. I had to learn some art history on my own, become myself an art writer and see the art that Stokes wrote about before I was prepared to provide an assessment of his books.

In the 1970s, when teaching philosophy in Pittsburgh, I read art history and travelled in Italy. By stages I learned enough to understand how exotic a writer Stokes is. And then in the 1980s I began to write art criticism myself. I did not often quote Stokes, but this practical experience gave me new insights into his writings. How do you find the right words to do justice to visual art? And how can a work of art be expressive? An art critic needs to answer these questions. You learn a lot about the theory of art writing, I found, by engaging in the practice yourself.

In this period I also read and wrote about art history. Writing as a philosopher, I studied the methodology of art history, focusing on the literature dealing with Piero della Francesca, Caravaggio, Manet and other European old masters and modernists. My Principles of Art History Writing (1991), a summary of that research, discusses two interrelated themes: the historical development of interpretation and truth in interpretation. Stokes does not play a role in that history (even when he wrote about much discussed artists, like Piero della Francesca, his accounts were generally judged to be eccentric in relation to normal art history writing).

Why, I asked myself, did art historians generally not take Stokes seriously? Wollheim notes that Stokes develops the English tradition defined by John Ruskin and Walter Pater. These art writers, all famous for fine writing, are hard to place in relation to art history. They are not doing, in an early, rudimentary way, what now scholars do in a more accurate way. Ruskin, who was appointed Slade professor, was a very eccentric professor of art; Pater, a classicist; but Stokes, because he was never a professor, remains harder to classify. Nowadays some distinguished art critics are outside of the academy, but few writers on old master art are able to sustain that role. Ruskin, Pater and also Stokes published autobiographies. This was one way in which they are highly personal scholars, more like creative writers than most present-day art historians. In my anthology England and its Aesthetes: Biography and Taste (1987) I gathered these materials, which I discussed in the introduction.

As my own practice as an art critic developed, I wrote a book about Charles Baudelaire, another creative scholar who is much admired by art writers.3 I was interested in reconstructing his aesthetic theory. Baudelaire’s criticism is an important resource for modernist historians, but they read him as a creative writer, not as a scholar. To praise an art writer for being creative can be backhanded praise – it is sometimes a way of saying that we are not especially interested in the plausibility of claims made in that person’s writing. But ‘my’ Baudelaire was a philosopher of art, a writer whose aesthetic I compared to Danto’s. Writing about his art criticism thus helped prepare me to analyse Stokes’s. Some important aesthetic theorising is not produced by art historians, and scholars interested in visual art should take seriously the contribution of such writers as Baudelaire, Danto and Stokes, who in very different and challenging ways rethink fundamental issues.

Let us proceed, then, by analysing Stokes, also, as a creative writer. This present analysis is inspired in part by Paul Tucker’s instructive comparison of Michael Baxandall and Stokes, published in the 2007 volume edited by Stephen Bann.4 In general, the practice of art writing proceeds without much close analysis of how it works. But just as we can better understand creative prose by identifying its linguistic qualities, the same is true for Stokes’s art writing. I have urged that we give close attention to the specifically literary qualities of writing about visual art in two books; both discuss Stokes.5 Here, extending that commentary in a more focused way, I analyse and then compare two of his descriptions of works of art. And I show what lessons this account reveals about Stokes’s development as an art writer.

The literature presents four ways of interpreting Stokes’s writings. Wollheim, who worked out the first detailed commentary, treats Stokes as an aesthetician, a philosopher of art who has a theory of the media of visual art.6 Alternatively, as Richard Read and Stephen Kite have demonstrated, Stokes can be understood in the terms of cultural history, by reconstructing his reading to grasp his theorising.7 Thirdly, we may compare Stokes with those art historical colleagues of his who also discuss the art that he interprets. Fourthly, and finally, we can read Stokes as a psychoanalytic thinker, a philosopher of art who develops the ideas of his personal therapist, Melanie Klein. At present these are all the obvious options. These approaches, which are ideal types, are not mutually exclusive. Wollheim discusses Stokes’s uses of psychoanalysis; and so, too, does Read.

It is instructive to chart briefly the comparative advantages and disadvantages of these interpretative strategies. Presenting Stokes as an aesthetician links him to philosophy, but does not show how to connect him with art history. And since nowadays art historians are unlikely to read aesthetics in the analytic tradition developed by Wollheim, this approach probably will leave him intellectually isolated. (So far as I know, Wollheim’s prominent defence of Stokes did not lead art historians to study him.) Treating Stokes in the terms of cultural history reveals the sources of his aesthetic, but it does not necessarily tell us how to evaluate his claims. What ultimately matters, it might plausibly be argued, is not how he arrived at his ideas, but what he said. Contrasting Stokes with his peers in art history allows comparison of interpretations, but it does not place him historically. And since he is in some ways very much a figure of his period, early modernism, this way of thinking does not reveal what he has to say to the present. Finally, right now when psychoanalytic art history is, fairly or not, marginalised within art history, presenting Stokes as a psychoanalytic aesthetician may not be a service to his reputation. Nor is it clear, at least to me, whether understanding his claims in relation to the theorising of Klein is the key to revealing the meaning of his books. One’s choice of interpretative strategy is in part personal – a reflection of one’s intellectual training. As I have indicated, my particular background heavily influences my writing about Stokes. And so I certainly do not want to pretend that my ways of thinking about these issues are more objective than they are.

I believe that right now Stokes is best understood by analysing the literary structures of his writing, and thus learning his aesthetic theory. Here I defend that sweeping claim by posing and answering a narrow question. Why was Stokes a mediocre art writer in 1926 and a great one in 1934? My goal is to compare and contrast two descriptions of works of art – I explain why one text is mediocre, and the other extraordinary. In my discussion of this question, I offer no evidence from his personal life, though I would certainly welcome speculation. My real concern is to explain and evaluate the change in his published writings.

Some writers and artists are great from the start, while others need time to develop, and so it is instructive to study their earlier creations. The historian needs to understand why sometimes it takes time for a writer or artist to find the right entry point, that moment when that person’s talents will lead to wide recognition. To cite a famous American example: Andy Warhol arrived in New York City in 1949 but only entered the art world in 1962. To understand his career, then, it is important to understand what went on during the thirteen years when he was an illustrator. Stokes, too, took some time to get going. He published The Thread of Ariadne (1925) and Sunrise in the West (1926), books that he did not want reprinted, before his first masterpiece, The Quattro Cento (1932),8 appeared. (Wollheim, who was his intimate friend, calls that ‘Stokes’s first book’. 9) What happened in the meanwhile? Why, I am asking, did Stokes’s writing improve so drastically?

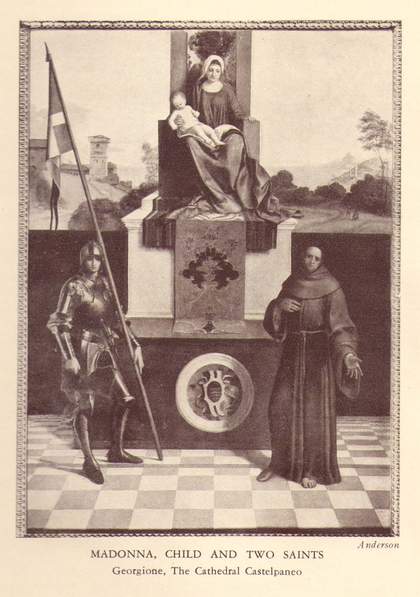

Fig.1 Giorgione’s Castelfranco Madonna (Duomo, Castelfranco) in the frontispiece to Adrian Stokes’s Sunrise in the West (1926)

The Castelfranco Madonna (1505; fig.1) is one of the few pictures attributed without controversy to Giorgione. Owing to the fact that this painting is in a small Veneto town, it is not as well known as some of his pictures. The Madonna and Christ are enthroned on a brilliant carpet, with two saints standing below. In his history of High Renaissance Italian painting, Sydney Freedberg compares and contrasts the painting with Giovanni Bellini’s altarpiece in S. Zaccaria, Venice.10 Where Giorgione connects his parts ‘into an arbitrary smoothed pattern to make a purified and artificial whole’, Freedberg says, Bellini is more concerned with illusionism – ‘the achievement of a counterpart of nature remains primary among his goals’. Contrasting similar-looking Venetian paintings of the same date with related subjects is a familiar art historian’s procedure. It offers a good way of identifying the distinctive features of the Castelfranco Madonna.

Sometimes art criticism presents a work of art as an expression of some abstract play of ideas. Stokes’s account of this Giorgione in Sunrise in the West does just this. It starts with an invocation of names of sculptors, who will play a key role in Stokes’s next book, The Quattro Cento: Francesco di Giorgio, Agostino di Duccio, Luciano Laurana.11 He then imagines the thoughts of the four figures in the painting: The Virgin, The Christ Child, St. Liberalis and St. Francis. ‘Unknown to each other’, Stokes writes, these figures ‘search the future, in communion only by bond of the simultaneous launching on blue-visioned voyages’. The description of the Virgin’s thoughts may carry conviction: ‘trusting thoughts lie deep within her sad eyes, yet she stares downward and traces the pattern of her faith upon the marble floor’. But the longer, more elaborate contrast of the saints’ musings is, in my judgment, less successful. St. Liberalis ‘has taken trust, not through the persuasion of doctrine, but from the ardour of blue skies, and his pagan figure and perfect armour rebut the slow curves of St. Francis’ Franciscan robe’.12

It might be instructive to identify precedents for his procedure, interpreting a history painting by articulating the thought of the individual figures. Although not short, his commentary has an oddly flighty feeling. We are not encouraged to focus on the picture as a work of art. Using the painting as the frontispiece is apt because Stokes is treating it as a condensed presentation of his larger argument. His aim, Stokes says in the Preface, is ‘to explain our present position as one stage before the apotheosis of Western Civilization’.13 The Greeks found a way to balance their lives, and in our very different culture we moderns can do the same:

We have discovered prose and poetry, the means to an end, the end in itself, and the supreme rule of their relationship, the sacred source of life itself and the secret of its everlasting youthfulness.14

In a sweeping history, from the Greeks thorough to medieval Catholicism, we come to the world of modern science, which has ‘discovered new facets of consciousness’ and ‘a perfection inconceivable to old Egyptian, Indian, Chinaman’.15 If I understand this speculative analysis, which is obscure, the stance of St. Liberalis is taken to anticipate art of the future. The book’s larger contrast between Prose and Poetry, which motivates the entire discussion, is not a way of thinking which has survived; nor is it either clear or in itself plausible. Stokes mentions this painting in his later books, but never again offers a sustained analysis.

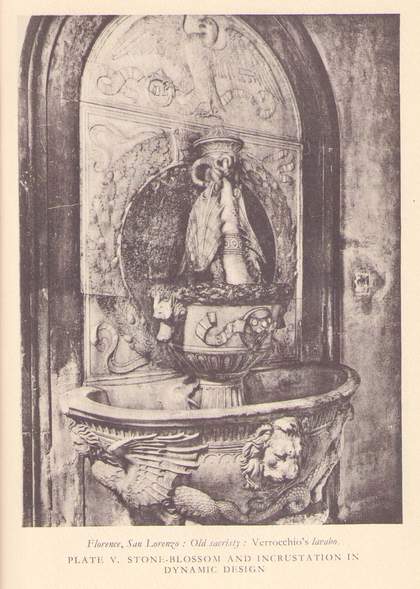

Fig.2 Andrea del Verrocchio, Lavabo, Old Sacristy, S. Lorenzo, Florence, reproduced as plate V in Adrian Stokes’s The Quattro Cento (1932)

Ten pages of The Quattro Cento are devoted to Verrocchio’s lavabo (1465), which is found in the old sacristy, San Lorenzo, Florence (fig.2).16 Unlike the Castelfranco Madonna, this is generally thought to be a minor work of art; Stokes’s claim that it is a masterpiece has not influenced commentary. The most recent full book dealing with Verrocchio, by Dario Covi, devotes only six pages to it.17 (And the long Wikipedia entry gives just one line to the lavabo.18) Stokes focused on the question of whether two artists had been involved in making the lavabo, an idea he rejects. Covi does not mention Stokes and indeed shows no awareness of the problems discussed by Stokes. In the 1970s, Marianne Novy, my wife, and I went to Florence with a Xerox of Stokes’s account and looked closely at length; no other art tourists interrupted us, either then or on subsequent visits. Few visitors not under the spell of Stokes’s account attend at length to this work. At the start, Stokes offers a subtle, highly condensed description of how he will understand the design of the sculpture. And at the conclusion, he links its balance with the objectivity of death, in which timelessness is perfectly achieved. He thus explains why he thinks this sculpture a masterpiece. For my present purposes, discussion of the interpretation itself is a large enough task, and since The Quattro Cento is readily accessible, I shall not here quote it at length.

Stokes begins by describing the falcon carved at the top and the decorative elements surrounding it. The lavabo is a container for holy water: and so associations to its contents inflect description of the carving. His next book, Stones of Rimini (1934), with its elaborate accumulation of lore about stone and its formation with water, enriches this reading. But this description is finer because it is so lovingly detailed; and because it does not depend upon the controversies surrounding the history of the Tempio.

After a very long paragraph of description, Stokes asks us to reflect on the use here of marble as a container for water. And then, in an admirably subtle transition, he describes the dynamic qualities of this relief sculpture. We learn about the Medici emblem; the boars and falcons and the vegetation represented; and the associations of these marine animals with water and the creation of stone, from which they are created, which here blossoms. Then Stokes stops, as it were to catch his breath – a good procedure, for we have had a lot to take in. After a brief note about the claim dating from Vasari, which Stokes dismisses, that this sculpture is the product of two artists, Stokes turns to reconsider it in terms of what he calls ‘stress and strain’. Our attention refocused, we look again. Earlier we moved almost effortlessly between description of the represented forms, their stony source and the function in a washing basin. Now, returning to the falcon, this time we are looking at the composition. The two griffins thrust one against the other, Stokes argues, so that the depicted forms achieve ideal balance. Perhaps the relationship of the represented forms initially appears to be stressful, but in fact they form a perfect whole.

Nothing in Sunrise in the West has prepared you for the sudden magnificence of this account. If you surrender to the spell of Stokes’s description you will feel that you can hardly look long enough at this sculpture. A detailed interpretation devotes many words to a single work of art. Judged by that standard, this account of the lavabo is a very full interpretation. Other art writers, it is true, offer extended interpretations: but whereas such accounts tend too often to use the art under scrutiny to stage some larger historical thesis, Stokes keeps our attention focused on this small sculpture. Drawing attention to art historical anticipations or parallels would take us away from close visual scrutiny.

Verbal descriptions of ideal wholeness generally are inherently problematic, for in order to describe unity a writer needs to identify the parts of that whole. Art writing, it follows, can never come level to the artefact described; but it can at least reveal its own ultimate limitations. Here I am hardly even beginning to summarise this super-subtle description, which demands that its reader walk around this sculpture. Art historians frequently describe the literary fantasies realised in visual works of art, but they are unaccustomed to speak, as Stokes does, of fantasies associated with the media of art. Even after many re-readings over four decades, I do not entirely understand Stokes’s interpretation. We read about the figurative significance of the sculpture; learn of the history of its medium, stone; and are reminded that a lavabo is a basin for hand washing. Since he praises Quattro Cento art for being present all-at-once, there is an obvious tension in his analysis. And at the end, I grant, the lavabo, for all of his sustained focus on its particular qualities, is the subject of generalisation: ‘What else’, Stokes asks, ‘is civilisation but a converting of formless power to organised show, to outwardness?’

Sunrise in the West sets the Giorgione in a shaky intellectual framework, using the painting as a staging point for a history of ideas. Quattro Cento gets us to look very closely at a sculpture, with the broad conception of carving set in the background. When Stokes moved from the abstract play of ideas of his earlier books to this focused close looking, he became a great writer. Even if you do not agree with his interpretation, or understand it completely, you are compelled to look closely. And he causes you to reflect on the linguistic recourses available to an art writer. You can stand in front of some important art and remain caught in digressive thoughts. When travelling in Italy, for example, it is hard sometimes to make the transition between driving or walking on busy streets and contemplating art. But when you do focus on that art, then you are taken out of yourself. Stokes admires the stillness of Quattro Cento carving. But, perhaps paradoxically this at-one-ness can only be identified using a great many words.

When I first encountered Stokes’s writings, I was too young to understand how reputations are formed. But I have learned about this process watching (and participating in) the development of commentary on other figures I have written about, Arthur Danto, Ernst Gombrich and Clement Greenberg. For a scholar’s writings to survive, he must attract commentators. (I say ‘he’ because all of these examples are male. But I have published a book about Rosalind Krauss – and soon one will be discussing other female scholars.19) Survival typically involves a struggle amongst rival interpreters. Who has the best reading – who, that is, is the legitimate heir? Such conflicts reveal that a scholar’s writings live. If you do not attract commentary, then it is hard for your books to survive. If an artist survives, his or her works are displayed; and essays and books are written about them. Scholars survive, analogously, because their claims get taken into the literature; others, Greenberg and Gombrich for example, because their successors take issue with their arguments.

Stokes was too far outside the art history world to survive in these ways. His interpretations are not much taken up in the literature; his style of argument was not influential enough to inspire emulation or critique. Some years ago, when I wanted to write a short intellectual biography of Stokes, I could not find a publisher. Thames & Hudson, who had published me, declined on the grounds that if they could not sell their three-volume edition of Stokes, they could not sell Carrier on Stokes. I have become sceptical about Stokes’s relevance to art history and, also, to my own practice as a critic. I was entirely misguided, I now realise, when I tried to relate him to art history. He is not where art history is coming from – nor where it is going. His early books sent me to Italy, and they prepared me to experiment with my own art writing, ultimately in terms which turned out to be very different from his – for I write about a great deal of contemporary art. But in that discussion, the relevance of his writings is as yet unclear.

In my opinion, the problem with focusing on a close-up reconstruction of Stokes’s life is that gathering of information does not necessarily explain why rather suddenly with The Quattro Cento he became a great art writer.20 And that is what needs to be explained if Stokes is to continue to attract readers. But this is often the problem with biographies: they do not tell us what most matters, why in our crowded art world a writer legitimately attracts our attention.21 Now Stokes’s visual culture has become distant. And his ways of understanding psychoanalysis have perhaps also become dated. Yet every time I return to his writings I am in awe of their originality and suggestiveness. Very few writers pay rereading in this way. I was very happy to see that this workshop was devoted to him. My utopian desire is that his writings become a living force. How can our present discussion contribute to that end? I have no answer to that question, which raises issues that deserves discussion by future scholars.

Notes

1. Richard Wollheim, Art and its Objects: An Introduction to Aesthetics , New York, Evanston and London 1968. I also studied with his colleague Arthur Danto, who, however, taught other subjects. At that time, he had published only one essay about aesthetics; not until later did he produce his now famous writings about the philosophy of art.2. Ibid., p.135.3. High Art: Charles Baudelaire and the Origins of Modernism , University Park, Pennsylvania and London 1996.4. Paul Tucker, ‘“Inferential Muscle” and the Work of Criticism: Michael Baxandall on Adrian Stokes and Art-Critical Language’ in Stephen Bann (ed.), The Coral Mind: Adrian Stokes’s Engagement with Architecture, Art History, Criticism, and Psychoanalysis , University Park, Pennsylvania 2007, pp.161–88.5. Artwriting , Amherst l987 and Writing About Visual Art , New York 2003.6. Richard Wollheim, ‘Introduction’ in The Image in Form: Selected Writings of Adrian Stokes , Harmondsworth 1972, reprinted as ‘Adrian Stokes’ in On Art and the Mind. Essays and Lectures , London 1973.7. Richard Read, Art and Its Discontents: The Early Life of Adrian Stokes , Aldershot 2002 and University Park, Pennsylvania 2003; Stephen Kite, Adrian Stokes: An Architectonic Eye : Critical Writings on Art and Architecture , London 2009.8. Republished, with a Foreword by Stephen Bann and Introductions by David Carrier and Stephen Kite, in The Quattro Cento and Stones of Rimini , Aldershot 2002 and University Park, Pennsylvania 2002.9. Wollheim [1972] 1973, p.317.10. S.J. Freedberg, Painting in Italy 1500 to 1600 , Harmondsworth 1971, pp.79–80.11. Stokes 1926, p.45.12. Ibid., pp.46–7.13. Ibid., p.x.14. Ibid., p.168.15. Ibid., pp.48–9.16. Stokes 2002; all my quotations come from ‘IV. Verrocchio’s Lavabo’, pp.58–67.17. Dario Covi, Andrea del Verrocchio: Life and Work , Florence 2005, pp.50–6. 18. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrea_del_Verrocchio accessed 1 February 2013.19. Rosalind Krauss and American Philosophical Art Criticism: From Formalism to beyond Postmodernism , Westport, Connecticut 2002.20. See my review of the biography by Richard Read, Art and its Discontents , in Burlington Magazine , vol.145, July 2003, pp.525–6.21. My own writings on Stokes are: ‘Adrian Stokes and the Theory of Painting’, British Journal of Aesthetics , vol.13, no.2, l973, pp.133–45; review of A. Stokes, The Critical Writings , Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism , vol.37, no.2, 1979, pp.243–5; ‘Adrian Stokes and Recent American Painting’, PN Review 15 , vol.7, no.1, l980, pp.50–l; ‘The Presentness of Painting: Adrian Stokes as Aesthetician’, Critical Inquiry , vol.12, no.4, l986, pp.753–68; the introduction to my England and its Aesthetes: Biography and Taste , London 1997; ‘Introduction to The Quattro Cento’ in Stokes 2002, pp.1-12; ‘The Art Historian as Art Critic: In Praise of Adrian Stokes’ in Bann 2007, pp.151–9; ‘Adrian Stokes: Art Writer and Painter’ in Adrian Stokes: Paintings , exhibition catalogue, Salander-O’Reilly Galleries, New York, 2–12 July and 12–30 August 2002.