This blog will focus on some of the items that have been digitised as part of the Archives and Access project; a broader selection will be displayed at a Show and Tell in Tate Library and Archive Reading Rooms on 4 December. Defining ‘Irish identity’ or ‘Irishness’ can be a vexed and tiresome business. On 20 July 1903, Hugh Lane, putative founder of modern art in Ireland, wrote to leading portrait artist John Lavery, soliciting support for his planned municipal gallery in Dublin (archive no. TGA 7245/230). Lane notes that many of the leading British artists of the day were in fact ‘quite Irish’. Lavery himself, for example, was born in Belfast, reared in Scotland, spent most of his working life in London with long periods in Dublin, travelled extensively, and died in Co. Kilkenny. This blog and accompanying Show and Tell will use Lane’s concept of ‘quite Irish’ – meaning Irish artists working abroad, or second generation Irish artists – to identify material relating to Ireland and Irish art held by Tate Archive.

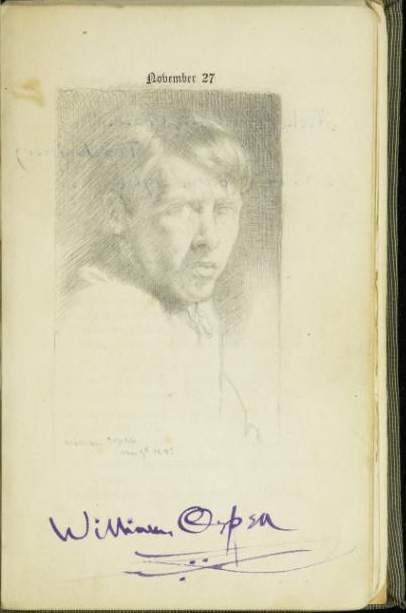

William Orpen, self-portrait sketch and signature, c. 1902Photography © Tate, 2015

In order to create his gallery, Lane needed the support of diverse social, cultural and political notables from Ireland, Britain and beyond. The milieu that sustained Lane is preserved in one of the more unusual collections in Tate Archive. Anita Bartle was an Irish journalist who wrote a column, This is my birthday, for the Daily Chronicle. On each day of the year a celebrity past or present would be commemorated by a series of quotes often humorously or ironically applied to the subject’s public persona. Two volumes of these columns were published in 1902, and Bartle used two copies as upscale visitors’ books; guests would mark their birthday with a signature, an inscription, a quotation, a bar of music or a picture. Donors to and supporters of Lane’s gallery contribute to Bartle’s volumes, such as artist George Clausen, poet W.B. Yeats, and playwright George Bernard Shaw. Lane’s great friend, travelling companion, and distant cousin William Orpen, whom he would task to finish a series of images of famous Irishmen for the gallery, sketches a haunting self-portrait in pencil. Lane pops up in other collections held by Tate Archive, most notably the diary of Henry Scott Tuke (another donor to the Municipal Gallery), who records several dinners with Lane, including a tantalising ‘long talk with Hugh P. Lane on his Irish adventures’ in 1903. Tuke presented To the morning sun to Lane’s gallery.

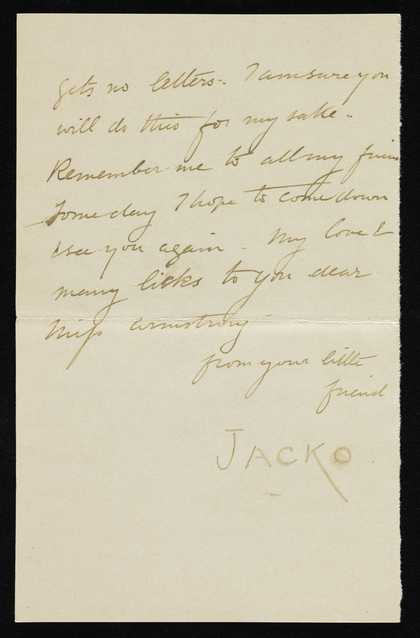

Letter by Stanhope Forbes, in the persona of his dog Jacko, Penmaenmawr, Wales, to Elizabeth Forbes, 15 August 1887© Estate of Alexander Stanhope Forbes. All Rights Reserved 2015 / Bridgeman Art Library

The core of the Municipal Gallery came from the collection of late railway magnate James Staats Forbes. Staats makes several appearances in the letters of his nephew, painter Stanhope Alexander Forbes to his fiancée and future wife, the Canadian artist Elizabeth Armstrong. Forbes was a pioneer of open air painting in British art, applying the lessons he learnt in Paris and Brittany to the Cornish coast. It is not always remembered, however, that he was born to a prominent Irish family and painted his first portraits in Dublin. His letters are among the joys of Tate Archive. A founder member of the New English Art Club, Forbes’ accounts of meetings and exhibitions are a major source for that pioneering movement in the history of modern art in the UK. He casts Walter Sickert and his ‘clique’ as villains of the piece, accusing them of imposing a ‘progressive’, formalist aesthetic at odds with the genteel academic naturalism of Forbes and his friends in the Newlyn School, who included fellow Irishman Norman Garstin. These friends are the subjects of many brilliant pen-portraits and set-pieces in the letters, and Forbes’ insatiable sociability finds him one night taking a carriage ride with Mr and Mrs Oscar Wilde. Forbes’ funniest letters record a trip to Wales with his parents. Here he portrays himself as a hapless sophisticate blundering about the Celtic landscape. On successive fishing trips he catches nothing, slips into the river, and attempts to rescue an apparently drowning dog who disdains his help. In one brilliant comic coup he writes to Elizabeth in the guise of Jacko, Forbes’ own beloved dog.

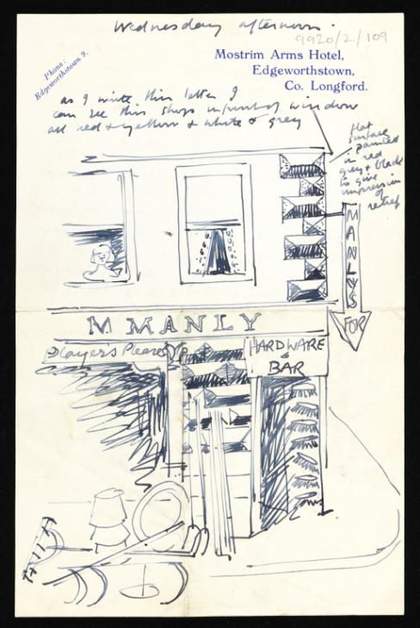

Letter from Kenneth Armitage to Joan Moore, Edgeworthstown, Co. Westmeath, 1941© The Kenneth Armitage Foundation

There is a lot of material in Tate Archive generated by the children of Irish migrants. One who engaged consistently with his heritage was sculptor Kenneth Armitage. Armitage’s disastrous upbringing by his Irish mother did not affect his feelings for her birthplace, and throughout his life he insisted on his Irish identity. One of the most engaging letters in his archive describes a fanboy letter he wrote to legendary naturalist, librarian and memoirist Robert Lloyd Praeger, arranging to meet him in Connemara to source marble for sculpting. This trip – planned in 1939 – was presumably cancelled at the outbreak of war, but a fascinating series of letters documents Armitage’s trip to Emergency Ireland in August 1941, on leave from the Royal Artillery. His descriptions of Dublin, Longford and Connemara, and in particular of the huge meals produced by his Aunt Elsie bely the dreary austerity with which this period is usually remembered in Ireland, and characterises the war-torn Britain Armitage has briefly escaped.

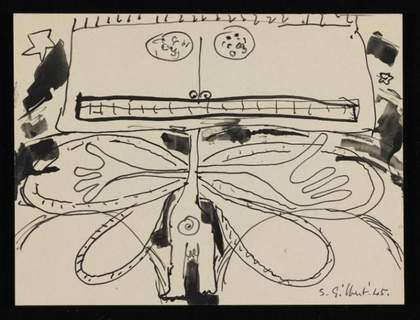

For centuries, artists travelled to Ireland, and in particular the West of Ireland, to search for a way of life they believed represented a simplicity and spirituality increasingly lost in a mechanised, modern world. This habit continued well into the 20th century, as items in Tate Archive confirm: Keith Vaughan’s 1954 drawings of currachs in Kerry, or Cecil Morris’s letters written in 1936. The Welsh baronet stayed in a ‘peasant’s cottage’ in impoverished Connemara, among ‘charming’ but ‘lazy’, ‘priest-ridden’ Irish natives who ‘never wash’ [archive no. TGA 8317/1/4/104-105]). A more original, surrealist-inflected response to Ireland is found in Ithell Colquhoun’s damply erotic watercolours of Donegal bogs. Stephen Gilbert was a different kind of British visitor to Ireland, seeking refuge as a conscientious objector during World War II. There he became a member of the White Stag Group, arguably the most influential movement in history of Irish modern art, and produced violent drawings of hybrid monsters.

Stephen Gilbert, Drawing of an abstract figure, 1945© The estate of Stephen Gilbert

Marie Seton’s letters to sculptor Ronald Moody in 1966 initially adhere to the Orientalist vein, her descriptions of friendly locals, bright cottages and picturesque ruins reading like a tourist brochure. Seton, however, was a lifelong socialist, biographer of film-makers Sergei Eisenstein and Satyajit Ray, a key figure in the early history of African-American civil rights, and intimate of the Nehru family. Where Morris could only find beauty and bad weather, Seton saw that the Irish landscape, ‘dotted with English fortifications and vast late period castles “writes” the history of domination and fear in vivid terms’, or was made desolate by countless famines and emigration; unsurprisingly she ends up in a Carrick pub singing IRA songs into the morning.

Letter from Marie Seton to Ronald and Helene Moody, Athlone, Co. Westmeath, and Dublin, 29 July-8 August 1966© The estate of Marie Seton

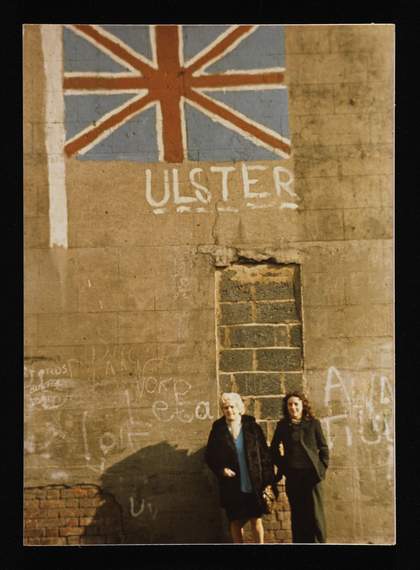

Seton’s 1966 letter ominously notes the growing sectarianism in Northern Ireland. This erupted into the Troubles in 1969, a cycle of violence and horror that would, alas, define most Britons’ experience of Ireland and the Irish for the next fifty years. Most material in Tate Archive relating to the conflict was produced by English leftists. Seminal among these is the image bank amassed by Conrad Atkinson for his controversial 1975 exhibition in Belfast, A shade of green, an orange edge. Atkinson’s archive comprises photographs of protest marches and sites of violence, and of the material culture produced on both sides of the conflict, from graffiti and murals to posters and textiles. However, Atkinson’s apparent even-handedness in collecting and exhibiting this material should be taken with a pinch of salt; he was active in producing work supporting the nationalist and socialist Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association.

Photograph acquired for Conrad Atkinson exhibition, A shade of green, an orange edge, Belfast, 1975© Conrad Atkinson

Landscape and political violence are predictable focal points for a discussion of Ireland and Irish art. More intriguing is the secret history of Irish homosexuality that can be traced through the writings of Walter Sickert (the fall-out of the Wilde scandal), Keith Vaughan (furtive assignations in World War Two London) and Francis Bacon (sunny, angst-free missives from gay coteries in North Africa). Or the influence of Irish artists on British art, as demonstrated by Duncan Grant’s wonderful account of an abortive pilgrimage to the famously elusive post-impressionist painter Roderic O’Conor. Items illustrating these stories, those mentioned above, and anything else that comes to light in the intervening two months will be on display at the Show and Tell in December. I look forward to meeting you all there.