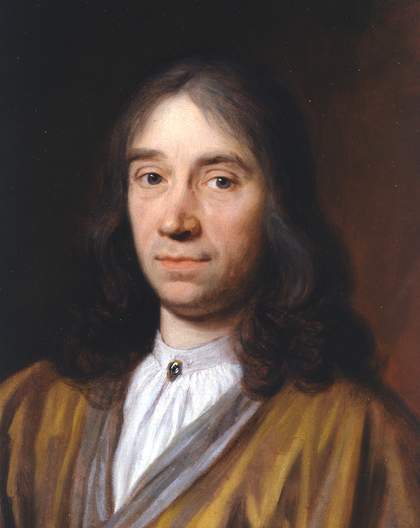

Fig.1

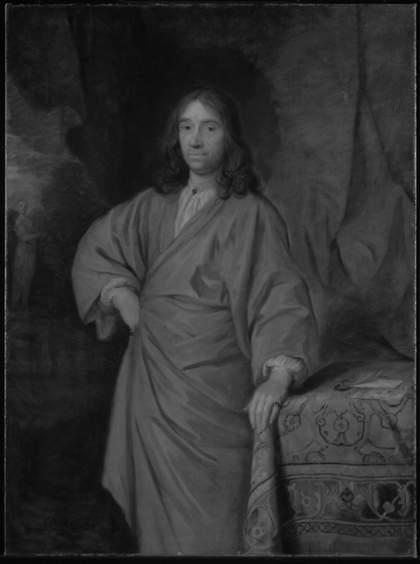

Sir Godfrey Kneller 1646–1723

Portrait of John Banckes 1646

Oil paint on canvas

1372 × 1016 mm

T05019

Fig.2

Detail of head and background of Portrait of John Banckes 1646

Fig.3

Detail of the banyan and hand of Portrait of John Banckes 1646

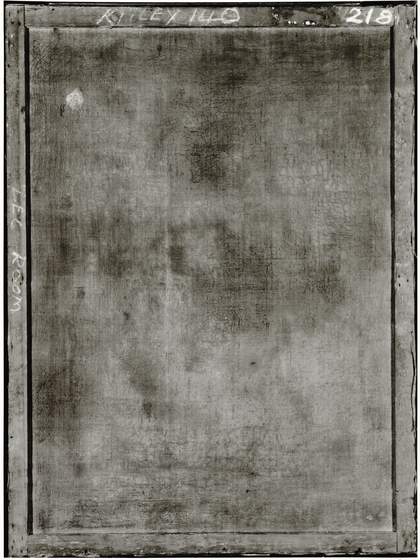

Fig.4

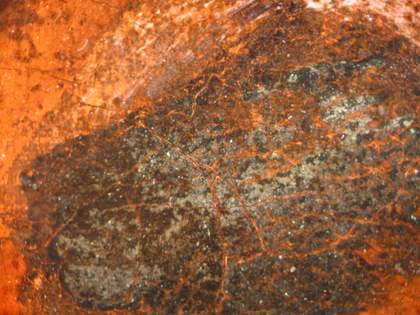

The reverse of Portrait of John Banckes 1646 when still on its original strainer

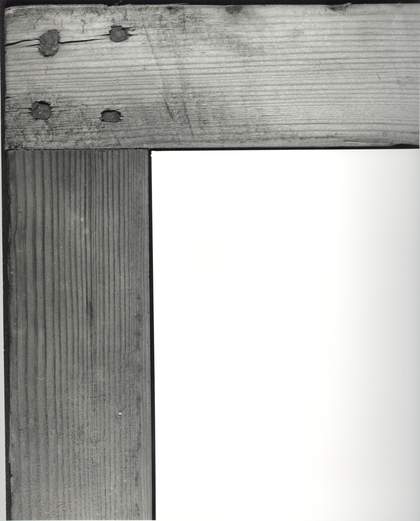

Fig.5

Detail of the top left corner of the original strainer, viewed from the front

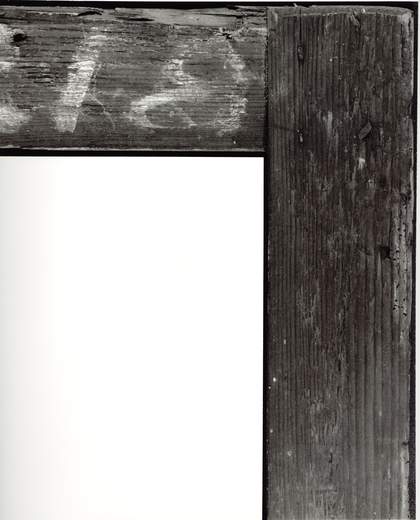

Fig.6

Detail of the top left corner of the original strainer, viewed from the back

This painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 1372 x 1016 mm (figs.1–3). The plain woven, linen canvas has a thread count of 15 vertical and 12 horizontal per square cm. The threads are of variable thickness and contain slubs. The painting is unlined and, until conservation treatment became necessary in 1990, was attached to its original strainer with original tacks (fig.4). The strainer, which has been retained in the conservation archive, is a simple four bar rectangle of pine. The bars are 47mm (2 in) wide and 15 (5/8 in) thick. Each half-lap corner joint is secured with four iron nails driven in from the front face to form four corners of a square (figs.5–6). The inside edges of the front face of the bars are slightly chamfered. The strainer is very lightweight and has suffered from extensive woodworm damage.

The portrait was probably originally painted laced to a loom, and then cut out of it and tacked to the strainer after completion. The cusping that is visible on all four edges must relate to the loom, as it does not tally with the tacking-points on the original strainer.1 Continuous paint on all the tacking margins indicates that the loom was slightly bigger than the strainer, although not by much or we would have lost more of the cusping.

The canvas was first prepared with substantial coat of animal glue size, which was allowed to dry before the ground was applied on top of it. The pale grey ground, although chalky-looking in cross-section, does not stain positively for protein with either acid fuchsin or amido black, so may be presumed to be oil-bound. Besides chalk and lead white, it contains opaque red and yellow particles, brown and black.2 Cross-sections show that it varies in thickness from hardly anything at the edges to 150 microns under the surface of the painting.

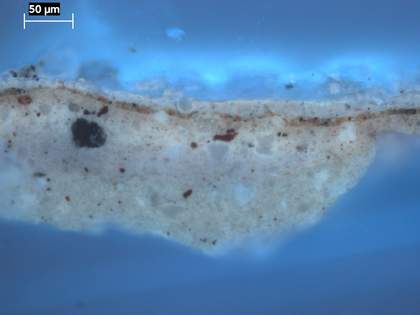

Fig.7

Cross-section taken from red curtain, 15mm in from the right edge and 522mm from the top edge, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom of the sample upwards: grey ground; pink priming; opaque tan-brown underpainting of curtain; red glaze on curtain (its fluorescence in ultraviolet light (fig.8) indicates a resinous or oleo-resinous binding medium); varnish

Fig.8

The same cross-section as fig.7 photographed at x320 magnification in ultraviolet light

The oil bound priming that covers the ground is dark pink (figs.7–8). It was deliberately left unpainted in parts of the banyan (the garment that Banckes is wearing) to help create the effect of shot silk but elsewhere the paint covers the priming entirely. The thickness of the priming in the cross-sections varies from 25 to 130 microns. It contains lead white, marine chalk, lead white, yellow and red earth colours, Cologne earth and charcoal black.

Fig.9

Infrared photograph of Portrait of John Banckes 1646

Fig.10

Detail with infrared photography of the head and background of Portrait of John Banckes 1646

Fig.11

Detail with infrared photography of the right hand and sleeve of Portrait of John Banckes 1646

Fig.12

Detail with infrared photography of the background statue in Portrait of John Banckes 1646

No undrawing is visible with the eye or by using infrared photography (figs.9–12). Some areas were laid in with underpainting, as follows: the head and probably most of the figure were sketched in with dark grey and brown paint, which was eventually left visible to form the dark shadows of the face and neck (fig.2); the curtain was underpainted with thin opaque paint in shades varying from brick red to dull brown to create the folds; the carpet was first painted with shades of bright opaque red paint; the left foreground was laid in with thin grey paint, applied with broad, sweeping strokes which were not directed to form any illusion of form. This grey colour forms the basis for the dark brown paint applied later to delineate the space.

Other parts of the picture were painted directly onto the priming, wet-in-wet. For example the linen, sky and foliage are densely built up with brushstrokes with no detectable preparatory work underneath nor glazing on top. The banyan was created with two shades of opaque yellow and grey, applied thinly with dashing brushwork, wet-in-wet but without much intermingling. The pink ground was left visible as the mid-tone of the shot silk. No subsequent glazing is evident. The baluster pillars are depicted as ‘negative’ space, in that they are defined only by the dark gap between them and they are not modelled tonally at all.

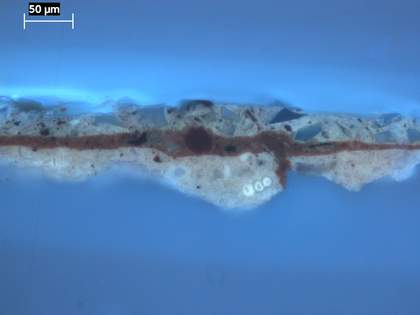

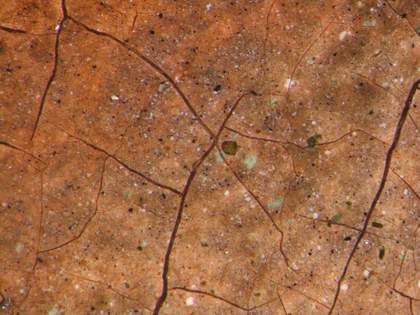

Fig.13

Detail at x8 magnification of a grey scumble over green carpet decoration

Fig.14

Cross-section through the area of carpet showing a grey scumble similar to that shown in fig.13, photographed at x 320 magnification. From the bottom: pink ground; opaque red of carpet; scumble of paint containing smalt

Fig.15

The same cross-section as shown in fig.14, photographed at x320 magnification in ultraviolet light

The red carpet appears first to have been glazed with crimson translucent paint (since faded) before opaque colours were applied to create the patterned border. The dark greenish blue areas of patterning were finally scumbled with a crusty layer of smalt to give the illusion of carpet-pile (figs.13–15).

Fig.16

Detail at x40 magnification of blue smalt in the yellow costume

Fig.17

Detail at x25 magnification of the greenish toned half shadow below the chin

Most of the colours contain smalt, probably to function as a siccative for the oil and, as a very transparent pigment, to transmit light into the paint film. Charcoal black is also present in most of the mixtures, including the flesh tones. The sky was mixed from lead white with smalt, charcoal black, cologne earth, chalk and vermilion. Foliage was mixed from smalt, charcoal black, lead white, green earth, cologne earth, burnt sienna and chalk. Shadows in the yellow areas of the banyan contain blue smalt, lead white, very fine yellow ochre, black, sienna and yellow lake (fig.16). Large particles of green pigment, probably terre verte, are visible at low magnification in the cool shadows of the face (fig.17).

Fig.18

Detail at x 15 magnification of microcissing in the paint of the white letter

The curtain was originally given a final glaze of translucent crimson paint, which has faded except where protected from light by the frame. The colour of the glaze would have been tempered by the brown underpaint, giving an overall russet colour rather than crimson. Otherwise the painting has not changed much. The pink priming is rather more visible in the banyan than it would have been originally because the paint is slightly worn there, but it was always intended to be seen there. There has been similar thinning of the paint in the sky, trees, red curtain and left arm of the gown. An interesting feature is the presence of microcissing in certain areas, for example the white paint of the letter (fig.18). Microcissing, which takes the form of minute craters and drying cracks in the paint, occurs when the paint contains a very high proportion of lead driers.3

The painting was given treatment at the Tate in 1990 to remove old varnish and old restorations and to reduce deformation in the support, after which it was strip-lined with Beva-371 film and polyester sailcloth and stretched over an aluminium-honeycomb support covered with a de-acidified canvas. The varnish is a modern synthetic resin.

September 2020