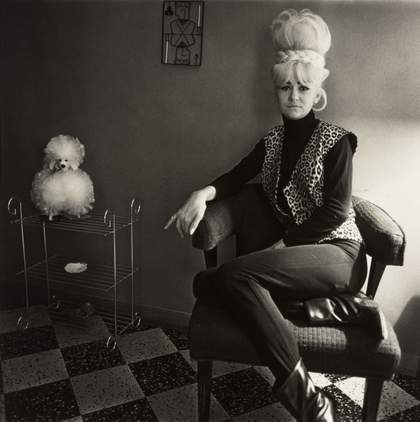

Lady Bartender at Home with a Souvenir Dog, New Orleans L.A. 1964

Diane Arbus, Lady Bartender at Home with a Souvenir Dog, New Orleans L.A. 1964 1964, printed after 1971

The Estate of Diane Arbus LLC

This photograph of a female bartender is composed like most portraits. The woman sits elegantly in her chair – not stiff, but clearly posing. The traditional aesthetic of the portrait photograph is subverted by the poodle ornament placed on the opposite side of the frame. The poodle is proportionally the same size as the woman’s hair. It does not feel as if Arbus is making fun of the hair-do, or of the woman’s taste in souvenirs. She merely picks out a joyful, quirky detail which asks us to re-evaluate our initial impression of the subject. This reflects the gap between intention and effect which Arbus found fascinating and often sought to capture in her work:

Our whole guise is like giving a sign to the world to think of us in a certain way but there’s a point between what you want people to know about you and what you can’t help people knowing about you… I mean if you scrutinize reality closely enough, if in some way you really, really get to it, it becomes fantastic. You know it really is totally fantastic that we look like this and you sometimes see that very clearly in a photograph. Something is ironic in the world and it has to do with the fact that what you intend never comes out like you intended it.

Diane Arbus Aperture Monograph

A Jewish Giant at Home with his Parents in the Bronx, N.Y. 1970

Diane Arbus, Jewish Giant at Home with his Parents in the Bronx, N.Y. 1970 1970

The Estate of Diane Arbus LLC

Photographing people in their homes is something which Arbus did frequently. It lends an intimacy to her portraits, which is almost voyeuristic. This image of a ‘Jewish Giant’ with his parents demonstrates a moment of interaction which is both humorous, due to the mother and father having to look up to speak to their son, and sensitive. The vignette created by the dark edges of the image seems to freeze the moment in time, as though we are peering in to a story book. This makes the image feel very familiar and normal, but at the same time sensational. As always, the photograph also reflects Arbus’s signature wit. Her photographs have been interpreted as disrespectful of these ‘freaks’, but others have seen them as a humanistic triumph. Arbus spoke about her admiration for the unusual people she photographed:

There’s a quality of legend about freaks. Like a person in a fairy tale who stops you and demands that you answer a riddle. Most people go through life dreading they’ll have a traumatic experience. Freaks were born with their trauma. They’ve already passed their test in life. They’re aristocrats.

Diane Arbus Aperture Monograph

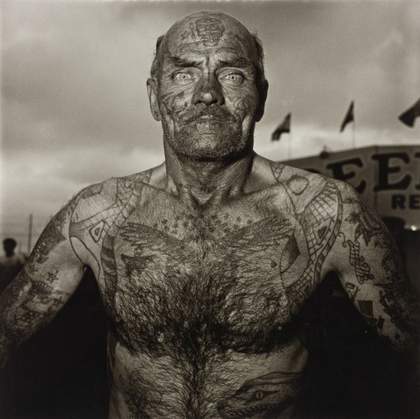

Tattooed Man at a Carnival, Md. 1970

Diane Arbus, Tattooed Man at a Carnival, Md. 1970, printed after 1971

The Estate of Diane Arbus LLC

Tattooed Man at a Carnival shows us Arbus’s flawless photography skills. The hyper definition picks up every tattoo, hair and wrinkle of the man, while retaining the grain of the film. The clarity lends itself well to the intense expression on the man’s face, enhanced by his pale irises and the closeness of the shot. By focusing solely on the man and letting the carnival in the background almost entirely disappear we are confronted with him as a powerful individual, rather than as a circus performer. Here Arbus explains her transition from love of grain to love of clarity:

In the beginning of photographing I used to make very grainy things. I’d be fascinated by what the grain did because it would make a kind of tapestry of all these little dots and everything would be translated into this medium of dots. Skin would be the same as water would be the same as sky and you were dealing mostly in dark and light, not so much in flesh and blood. But when I’d been working for a while with all these dots, I suddenly wanted terribly to get through there. I wanted to see the real differences between things… I began to get terribly hyped on clarity.

Diane Arbus Aperture Monograph