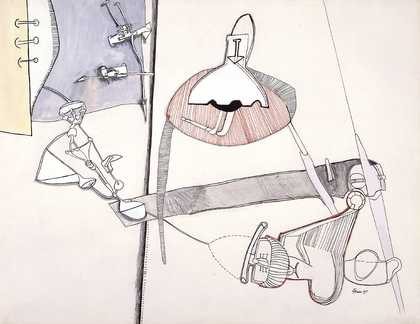

Stephen Korbet, portrait of Eva Hesse c.1959

Photo: Stephen Korbet

Simon Grant

The first and obvious question Helen. What was Eva like when you were growing up?

Helen Charash

That is the infamous question. What was it like to grow up with a genius? We were very ordinary children. We had a park near to where we lived and we played together there. And I don’t even remember whether a grownup would take us there. Life was very different then. There weren’t all the dangers that are real or perceived today. We were very different personalities. I was much more serious. My father, who kept a journal, always wrote that Eva was like an imp. We were both good students, but she was, even from the beginning, much more of a risk-taker.

Simon Grant

Much has been written about the kind of trauma of your childhood and the effect your mother, who committed suicide in 1946, must have had on your lives. Do you think that’s the real reason she was drawn to become an artist?

Helen Charash

No. I think the art was very much a part of who she was. My mother was very creative – not only with drawing and sculpture, but sewing, cooking and many other things. That said, I’m sure that our background had an impact on us. I mean, we both had baggage. And Eva had a real issue of abandonment.

There were traumatic things that happened to us when we were very young. As my father wrote in the diaries, she was under three, and I was a little older, five, when my parents left us on this train station with the Gestapo dressed as Customs officials. He wrote that they didn’t know if they would ever see us again. As I don’t remember it, what I know from the diaries, that a twelve-year-old girl was put in charge of us on our train journey. We were supposed to go to my father’s brother in The Hague, but the Nazis didn’t allow that, and so we were put in an internment camp and were quarantined. I didn’t understand that sort of thing. And I do remember several incidents. It was going to be Eva’s birthday – which was January 11th. She was sick but they wouldn’t let me see her. I always thought it was a nunnery, but it wasn’t, it was an internment camp, probably staffed by nuns. I remember that they wouldn’t let us out, and were very strict. Eva had been toilet trained, but she regressed and they spanked her. I don’t remember them at all as being cruel. But to be without your parents at that young age…Eva, of course, writes about it later on in her journals. Then my mother dying, of course, was another abandonment for her.

Simon Grant

At one point Eva wrote: ‘Maybe I’m not as smart as the men, not intellectual enough. Maybe emotion is just as good as intellect.’ How do you think Eva managed in the male-dominated art world of the 1960s?

Helen Charash

Well, she felt very strongly about that, and she expressed herself vehemently. She believed that her work was as good as theirs and was as cutting edge for that time as the male artists, and she was very upset about not being in the important galleries such as Leo Castelli.

Simon Grant

She went on to say: ‘I’m so insecure, yet I know I can make great art. All my life I’ve been either the cockroach or the Queen’. What did she mean by that?

Helen Charash

Well, you know, Eva was ambivalent. She knew she was a great artist, but she was…so young, remember. And there was such a short time from the time that she came back to the States from Europe until she took sick in her early thirties. Whenever you pushed forward, especially women, and especially at that time, were pulled back a little bit in the sense that they needed to say again, ‘I can do it!’ But it was so difficult for her in that environment. Her marriage broke up too. But they really probably weren’t right for each other from the start. They were both very passionate people.

Simon Grant

However fairly early on she had good supporters in the form of artists like Robert Morris (who included her in a group show Nine at Leo Castelli warehouse in December 1968, as well as Sol Lewitt and Donald Judd. Sol LeWitt wrote a very nice line to Eva: ‘Don’t worry about cool; make your own uncool.’

Helen Charash

Yes, absolutely. Shortly after she died, Sol did a big wall drawing for her (called Wall Drawing # 46: vertical lines, not straight, not touching, uniformly dispersed with density covering the entire surface of the wall) at the Galerie Yvon Lambert, Paris. They had a very close relationship.

My feeling today is, with all her ambivalence and all her problems, the positive force was always the art. Sol, as an artist, understood this, and understood how great she was, and that she just needed to push through. But Eva was not a quiet unhappy person through all of this. I have a vignette that will give you an idea of this. When I was seeing the man who would become my husband, he came to our house. He was a young, dashing, good-looking guy. Eva opened the door in a miniskirt, and black, stockings. He said, ‘Oh my God, I think I have asked the wrong sister.’ So that’s the way Eva was – she was extraordinarily attractive and she was fun-loving. And she had a lot of guys. So it wasn’t a dark picture. You can feel the energy in her work. She and her husband Tom must have had a very passionate time. Then they got married and had the problem of work… of life. Of two artists working together… I have always felt that she sublimated her work to Tom’s in the first year of her marriage.

Simon Grant

She was obviously serious about her work, but did she find humour in it as well?

Helen Charash

There was humour, but whether she found that to be…you have to think so. Can you make work that is so…you know, that has that has this twist to it and not feel it? I don’t know.

Simon Grant

Tate has several of Eva’s works. I’d be curious to know what you think of them.

Helen Charash

I think they are fantastic. In them I see the dangers of life. Different parts of our personality, of our being. The drawings are like journeys or processes. In he processes of some of her drawings, they get less and less detailed and finer and simpler. Drawing was always her favourite medium. As she explored each theme, she always came back to the drawing. Did Eva always draw? I can’t remember. My daughter…I mean, she didn’t do anything in art, but she always drew and always doodled.

Simon Grant

Do your children like Eva’s work?

Helen Charash

Oh yeah, both my kids. You know they have grown up with it. Even though they were children when Eva died, but they’ve gone to see most of Eva’s exhibitions to most of these exhibitions. The whole family was here at Tate show in 2003. They are part of this journey, and the younger generation know that Eva did work of that kind, and that she is an important artist to a lot of people around the world. Wherever I have been in the world over the years, I have come across so many people who have a connection or bond with her work. People have said – I’ve learnt so much from her, she’s so important. and so relevant. It doesn’t matter what age they are.