Paul Klee

Burdened Children (1930)

Tate

Paul Klee did many things in many different ways. A great artist, he was also a sympathetic teacher, fine musician, and persuasive writer. His work was diverse. Even paintings and drawings that he was working on at the same time could be very different in style and technique one from the next.

Within all the variety of his output, Klee also liked order. So, in that spirit, this A-Z will list some of the things that made him remarkable, and some of the circumstances that contributed to him being one of the most significant artists of the first part of the twentieth century.

A is for Ambidextrous

Klee was ambidextrous. He wrote with his right hand and painted with his left. This means that his watercolours were painted with one hand, but signed and titled with the other. This ability must also have helped, and been maintained, by his gifts as a violinist.

Klee taught at the Bauhaus, the modernist school of art and design between 1921 and 1931. There is a story that he began his first class by avoiding eye-contact with his students, and simply approaching the blackboard and drawing two arcs at the same time with a chalk in either hand. The result magically came together as a fish.

B is for Bears

Klee was born in the town of Münchenbuchsee outside Bern, the capital city of Switzerland, on 18 December 1879. Within a year after his birth, the Klee family left the municipality and moved south to the Swiss capital. Featuring on the city’s coat of arms, bears are the symbol of Bern and there is a sculpture of a bear in armour in the main street known as the Zähringerbrunnen or Zähringen Fountain. Built in the 1500s as a memorial to Berthold V, duke of Zähringen, who founded the city in 1191, the story goes that a bear was the first animal killed by Berthold V in the founding year of the city. This legend is said to be the source of the city’s name and, to this day, bears still live in a special enclosure near the city centre.

Klee’s youth was spent entirely in the Swiss capital, and the bears (both live and sculptural) may have helped to fire his imagination. However in 1898 he moved to Munich to go to art school. After marrying the musician Karoline Stumpf, known as Lily (more on Lily below), and settling in Munich in 1907, he frequently holidayed in Bern. This family connection allowed him and his wife to retreat there in late 1933, when the Nazis stripped him of his teaching post in Germany. He did not leave Switzerland again.

C is for cats

Throughout Klee’s life cats were part of the family. They appear in his letters and his photographs, and even as subjects of his works. Fritzi the cat was ever-present in the 1920s, whilst Bimbo was central to the later Bauhaus years, followed by a second Bimbo who moved with them to Switzerland.

One particular anecdote of the painter’s feline-fondness came from the American art collector, Edward M.M. Warburg, who visited Klee (and his cat) to look at some works on paper. He recalled seeing the cat start to walk across a still-wet watercolour and tried to stop him, afraid that he would leave a paw-print. But Klee is said to have simply laughed, and told him to let the cat wander as he liked. ‘Many years from now, one of your art connoisseurs will wonder how in the world I ever got that effect’, he explained. Whether or not this account is true, it shows Klee’s openness to unexpected developments.

D is for diaries

Klee began to keep a diary as a student and maintained one until 1918 – but at that point, made a concerted effort to go back and edit them. He not only imposed order on his sometimes lengthy entries, but also added sections and cut out others that he presumably regretted writing. So you can come across a bit of the diary from 1908, but it was actually written in 1918 – and there are places where he writes in his current present tense, which is rather confusing.

Although he supplied passages to three authors who wrote the first monographs on his work published in 1920–1, he doesn’t seem to have planned to publish the diaries as a whole. His son, Felix Klee, produced an edition in 1964 that was widely translated into English in 1968. They are the best sources of Klee’s early ideas, but not entirely reliable because of his process of revision - so they’rebetter seen as autobiography rather than chronicle.

E is for Egypt

Egypt had been a place of fascination throughout the nineteenth century, combining the attractions of the ancient monuments with the lure of the exotic. Klee seemed to have wanted to go there since his brief trip to Tunis in 1914, and in 1922 a new wave of Egyptomania had been initiated by Howard Carter’s discovery of the untouched tomb of Tutankhamun. Eventually, Klee spent a month in Egypt at the end of 1928 and early 1929, taking the tourist trail from Cairo – where he saw Tutankamun’s treasures in the museum – to Luxor and the Valley of the Kings.

Klee produced sketches in Egypt and some more work when he went to Tunis, but really it’s the legacy of this period that is important. Some of his later paintings, such as Fire in the Evening and Steps, contain an echo of Egypt, although they’re not explicit paintings of pyramids and the like. And later in his career Klee did depict sphinxes in a number of works.

F is for Fishes

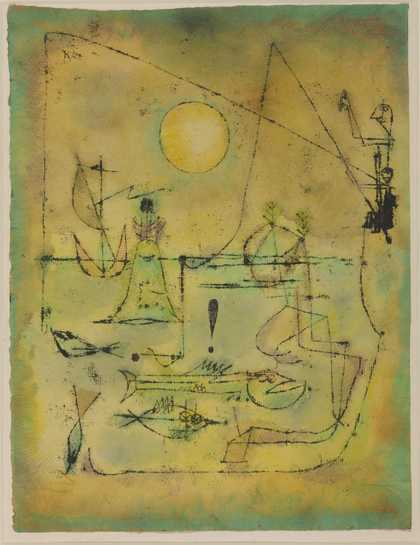

Paul Klee

They’re Biting (1920)

Tate

The German painter and watercolourist Paul Klee had an aquarium in his house, and was fascinated by the movement of his fish in three dimensions. He would discuss this with his students and it became the subject for several paintings through the 1920s. Where Around the Fish shows a meal, the teaming world of fish is explored in Aquarium. In the aptly titled Fish Magic, the presence of the creatures seems to cast a spell like Papageno’s music box on the birds in Mozart’s The Magic Flute, with curious people appearing at the margins as if mesmerised by this entrancing world.

G is for German

Throughout his life Paul Klee was a German citizen. Though he was born and died in Switzerland (and spoke ‘Schweizerdeutsch’ at home), he inherited his father’s nationality. This reflected a fluidity across Central-European borders as part of a sense of a shared culture in the later nineteenth century. The consequences were otherwise.

As a German, Klee was conscripted into the army in the middle of the First World War (although he served behind the lines). Klee found himself applying for Swiss citizenship on his return to the city of his childhood in 1933. The rules required a five-year residency before nationality could be considered and conferred. Klee’s application in January 1940 was being processed as his health declined and notification of its success arrived shortly after his death in June that year.

H is for Hans

Hans Klee, father of Paul and Mathilde, appears to have been a domineering character. He was a lasting presence in the painter’s life, dying at the age of 90 only months before his son, who died at the age of 60 in 1940. Hans Klee’s career as a teacher of music teachers at the Cantonal Teachers’ College made him an influential figure on generations of Swiss musicians.

Growing up in a musical household clearly had a significant effect on Paul Klee, also an accomplished violinist whose love of music often leaked into his work – as well as his social life. Nicholas Fox Weber, a friend of the artists Josef and Anni Albers, recounted how the pair would go to the Klee household for a social visit, in which the artist would spend the evening not talking but entertaining them with Mozart and Bach on the violin, accompanied by his wife, Lily, on the piano.

Hans Klee seems to have been sceptical of his son’s career as a painter, but evidently proud of the results. In 1917, the poet Hugo Ball recorded his arrival in Zurich, just as a lecture on his son’s exhibition was finishing: ‘An old man of nearly seventy. I would have liked the lecture to begin again, and the audience to be called back by telephone… But he was very pleased to see his famous son’s pictures.’

I is for Ida

Ida Frick, the mother of Paul and Mathilde, was a singer, and – along with Klee’s father, Hans, a music teacher – inspired the musical atmosphere of the Klee household at Obsterweg 6 in Bern. In contrast to her gregarious and forceful husband, Ida was rather sickly, and died quite young of a debilitating illness almost twenty years before Hans. While in Weimar, Paul Klee recorded being visited by her in his dreams when she died in Bern in March 1921.

J is for Jena

In January 1924, Klee delivered a carefully prepared lecture at the Kunstverein – the public art gallery – in Jena, a city in central Germany. He made a case for the artist’s need for freedom of the imagination. This was a familiar theme, but one that he articulated with especial clarity. It is typical that he pointed out that, while everyone would recognise that there is a relationship between the buried root system and the visible crown of a tree, no one would expect them to be identical. In much the same way, Klee argued, artists act as interpreters of the worlds that feed their art but should not be expected to be identical with the visible. The lecture was published after his death, in English simply as Paul Klee on Modern Art.

K is for Kairouan

Of the stories that gathered around Klee perhaps none is more powerful than the one that he encouraged about his visit to Kairouan. ‘Colour and I are one’, he wrote in his diary, in response to his stay in the Tunisian town in April 1914. Though this comment may have been written later, the sentiment that Klee encouraged was that he ‘broke through’ from his skill as a draughtsman into colour during his North African trip. He even hinted that his Swiss mother might have had ancestors from the region, so powerful was the adventure. What is clear is that the experience of Kairouan, visited with the painters Auguste Macke and Louis Moilliet on the eve of the First World War, fuelled Klee’s work for years to come.

L is for Lily

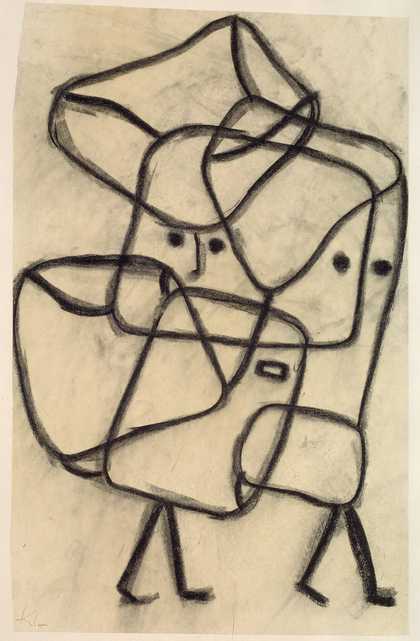

Paul Klee

Walpurgis Night (1935)

Tate

Karoline Stumpf, known as Lily, met Paul Klee at a concert in 1899. Throughout their lives together, music underpinned their relationship. An accomplished musician, Lily evidently had a rebellious response to her father’s dismissal of Klee’s attentions. They met in secret, were secretly engaged and, in 1906, were married in Bern rather than her family home. When they settled in Munich it was Lily’s piano lessons that sustained the household.

Once Klee was appointed to the Bauhaus, Lily was able to afford treatment for her precarious health at spas in Germany and Switzerland. Her tenacity was seen in the role she played in transferring the household to Switzerland in 1933 and, after Klee’s death in 1940, in establishing a public legacy for his work.

At a crucial moment following Klee’s death, as Lily was very old and unwell, an agreement was made in Washington allowing the allies to sequestrate German assets abroad, and as both Lily and Paul were still German citizens, she feared that the Klee’s work would be seized and distributed randomly. In the moments before she died, Lily signed an agreement securing Klee’s work as a collection with a charitable purpose, and it was assigned to a number of public collections in Switzerland.

M is for Magic

One of the most frequently used descriptions of Klee is that he was a wizard or magician. This is especially common at the Bauhaus, where he was contrasted with artist-engineers, like László Moholy-Nagy, who were his colleagues. Klee fed this impression. He insisted on the hand-made nature of his work, making paint, glue, mounts, even brushes, himself.

He kept his Bauhaus studio locked while he worked, only admitting colleagues and students on their agreed knock and at specific times. One colleague called it ‘the wizard’s kitchen … the place where real magic potions were brewed’.

N is for Nazis

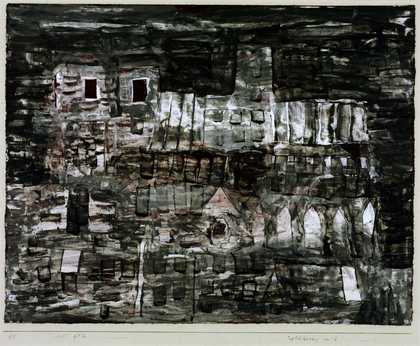

Paul Klee

The Castle Mountain of S. (1930)

Tate

In 1930s Germany, the National Socialists fixed on what they perceived as a corruption of culture in the Weimar Republic as a target for attack. It was an excuse for anti-Semitism, anti-Communist, repression. When Hitler become Chancellor on 30 January 1933, a devastating assault on the plurality of German culture ensued.

As a modernist, Paul Klee was dismissed from his teaching post at the Dusseldorf Academy. His works were removed from public galleries, his collectors were hounded and his dealer Alfred Flechtheim forced out of business as a modernist and a Jew. More fortunate than many colleagues, Klee could return to Bern where he settled in late 1933, as the cultural world in which he had lived was systematically destroyed.

O is for oeuvre catalogue

Klee was a meticulous, methodical artist who listed all of his artistic endeavours in an ‘oeuvre catalogue’. Klee began to list his works in 1911. Each ad the year and a number, with these being inscribed on the front of drawings and watercolours alongside the title. He kept up the listing until the end of his life. As well as the allotted number, he kept a record of the technique and any sales.

In the earliest catalogue volumes sales are extraordinarily scarce. Even after he began to show regularly in Berlin and Munich, his productivity outstretched his circle of admirers. As well as revealing a highly systematic approach to monitoring his own work, Klee’s oeuvre catalogue offers an idea of sequences of paintings made alongside each other in the studio and shown alongside each other in his exhibitions.

P is for Paul Klee

Born on 18 December 1879. Klee came from a generation that would shape the modern world. Albert Einstein (who published the Theory of Relativity in Bern in 1905) was born in March 1879, Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso in 1880 and 1881 respectively.

Anni Albers told the story of the celebrations at the Bauhaus for Klee’s fiftieth birthday in 1929 (as recounted in Nicholas Fox Weber’s In The Bauhaus Group: Six Masters of Modernism). Hiring a Junkers aeroplane, manufactured locally in Dessau, she and other students parachuted an angel-shaped package of gifts onto the roof of Klee’s house. Much as inspiration seemed to fall from the sky, so did praise; one collector at the time simply called him ‘our greatest German artist.’

Q is for quantity

Klee showed his work in surprising quantities. In 1920 he included 362 works in his first solo exhibition at the Galerie Neue Kunst Hans Goltz in Munich. It had a remarkable impact and established his reputation. His later exhibitions continued the pattern. At the Nationalgalerie in Berlin in 1923, Klee included 270 works, and two years later showed 214 at Goltz’s. Art dealer and collector Alfred Flechtheim showed 150 Klees in Berlin to mark the painter’s fiftieth birthday in 1929. On returning to Switzerland, Klee selected 273 works for the Bern Kunsthalle in 1935, and a further 213 in his final lifetime show – Paul Klee: New Works – in February 1940 at the Kunsthaus Zurich.

Given such striking statistics it is perhaps not surprising that Klee’s dealers became concerned that he might compromise sales by seeming to be over-productive. Rather than reducing his output or the size of the exhibitions, Klee introduced a letter code to his numbering system that disguised his productivity.

R is for Reputation

Once his public standing became established in the mid-1920s, Klee, like many artists of his generation, was often compared to and contrasted with Picasso.

The Czech writer Karel Teige remarked on the impossibility of describing Klee’s paintings, concluding: ‘We can merely say that, together with the works of Picasso and de Chirico, they represent the most poetic values of contemporary art.’ In 1934, another reviewer suggested: ‘Both Klee and Picasso stand, as it were, on the very edge of consciousness … eager to catch a glimpse of the ultimate frame of existence.’

Perhaps the greatest impact of Klee’s work came soon after his death, when the scope of his production was revealed in memorial exhibitions. ‘A realisation emerges, perhaps a little unexpectedly’, wrote the New York critic, Sidney Janis, in 1944, ‘[that] if there is any artist after Picasso, the character of whose work runs through twentieth-century American painting … like a recurring theme, it is Klee.’

S is for Satire

Although Klee’s early prints failed to secure him work on the Munich satirical paper Simplicissimus, satire was a mode that persisted throughout his career. It may be seen to re-surface in the ‘oil-transfers’ of 1920–2, such as Memorial to the Kaiser (whose abdication coincided with the end of the First World War) or the ironic self-portrait Ghost of a Genius (1922). It flavours the humour of Fish Magic 1925 and Puppets 1930. It may even soften the threat of the late paintings of witches, who stand for the nightmarish collapse of European values.

T is for titles

Klee inscribed allusive titles on his drawings and watercolours for all to read. A cubistic structure from 1913 is called When God Considered the Creation of the Plants (suggesting there were other options), while a gradation of 1922 is called Hanging Fruit. More fantastic are the narratives augmented by such titles as Primeval World Couple.

In the period of crisis in 1933–4, with his enforced return to Switzerland, his titles became bleaker. A work acquired by his former colleague at the Bauhaus, the architect Mies van der Rohe was called The Man of the Future; whether optimistically or ironically is difficult to discern. Bewitched – Petrified (1934) brilliantly summarises the anxieties of the period, just as Outbreak of Fear captures Klee’s sense of mortality in 1939–40.

U is for underlining

Once Klee had completed a drawing or watercolour, he took care to mount it on card. This sometimes involved extensions of coloured paper at the edges, that (as in the case of the red addition to With the Rainbow) could transform a composition.

A further touch came with the fine ink line drawn below the work on the backing card. Sometimes echoed at the top, the underlining provided additional balance and became the margin around which Klee located his number, title and (often creeping onto the work itself) signature. It was part of finishing. Even when the title slipped below (in the early 1920s) and required a further line of its own, the effect was to provide stability and it continued as part of Klee’s practice until almost the end of his life.

V is for violin

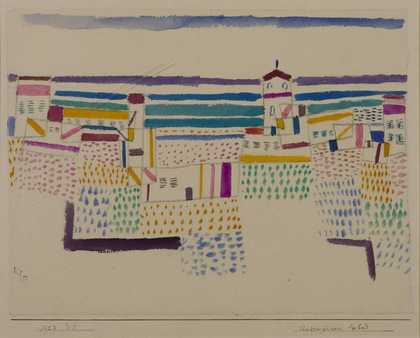

Paul Klee

Seaside Resort in the South of France (1927)

Tate

Klee was an accomplished violinist, playing in quartets and in an orchestra in the Swiss capital Bern, touring to neighbouring cities in 1902–6. The quartet’s repertoire included Beethoven, Brahms, Mendelssohn and Mozart. Once he was married to pianist Lily, they played violin and piano pieces together and even gave concerts in support of the Bauhaus in the 1920s.

Both Klee and Lily lived rich musical lives, regularly attending performances across Germany in Munich, Weimar, Jena, Dessau and Berlin, as well as on their holidays. Although appreciating contemporary composers (such as Paul Hindemith) and performers, many of whom he met at the Bauhaus, Klee seems to have believed that his own talents were suited best to the classical repertoire learnt in his youth. Mozart remained his measure.

W is for writings

Klee kept his published texts on art quite short. His Creative Confession that appeared in 1920, opened with the famous assertion: ‘Art does not reproduce the visible, rather, it makes visible’.

Originally published at the Bauhaus in 1925, Pedagogical Sketchbook condensed his early teaching notes. The title shows how it combined educational importance with artistic exploration. He began: ‘An active line on a walk, moving freely, without a goal. A walk for a walk’s sake. The mobility agent is a point, shifting its position forward.’ This is followed by a sketch of a serpentine line that one can imagine Klee drawing on the blackboard in his classroom. By suggesting that the line makes its own decision about taking a walk Klee introduced his audience to more methodical and theoretical concerns. Pedagogical Sketchbook remains in print as one of the most influential books on the creative method.

X is for 'X Above Left'

One of Klee's 1915 watercolours is known as With Green X Above Left. This simple description nevertheless draws attention to the artists use of alphabetical, mathematical or other symbols. In this particular piece, the X anchors the nearby planes of colour and helps to emphasise their flatness.

Elsewhere a ghostly X floats above the more definite T in a work titled Picture with Letters painted in 1924. They sit as if laid-on the surface, though are too evidently hand-painted to pass for the stencils or collage of cubism.

Y is for 'A Young Lady's Adventure'

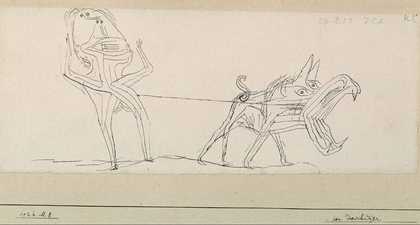

Paul Klee

A Young Lady’s Adventure (1922)

Tate

A tale seems to unfold in A Young Lady’s Adventure, but quite what it is remains obscure. There is a magical atmosphere. The ‘Young Lady’ and her long-jawed dog encounter a bird in a darkened forest. The red arrow may mark the path or suggest a threat, or both.

Although the space is different, much the same may be said of the contemporary Main Scene from the Ballet ‘The False Oath’ also from 1922, in which a shadowy arrow is outplayed by the huge exclamation mark. It descends on the performers. In these works Klee showed how he could hold the balance between narrative and open-endedness.

Z is for Zoo

Klee was, presumably, stimulated by the visual variety of nature brought together in zoos. On 27 December 1928, for instance, he was in Cairo and visited both the treasures of Tutankhamen at the Cairo Museum and the city’s zoo (the setting of which he admired).

In March that same year he had been on more familiar territory. The day after the opening of his exhibition at the Galerie Flechtheim in Berlin, he went to the zoo before going on to see Charlie Chaplin’s hit film The Circus, and then to visit his friend, the critic, Carl Einstein. The day summarises some of Klee’s many interests: nature, popular entertainment and intellect.