Introduction

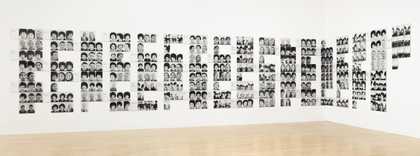

In From Tarzan to Rambo... artist Sonia Boyce explores her own sense of self in relation to media images of blackness and whiteness. The work explores the complex interweaving of black history with classic Hollywood narratives and other mass cultural forms. Boyce creates powerful stereotypes of white male supremacy, while presenting black people as foolish 'natives'.

The full title of the work is From Tarzan to Rambo: English Born ‘Native’ Considers her Relationship to the Constructed/Self Image and her Roots in Reconstruction. Sonia Boyce is the 'English born Native' of the title. In the work she explores her desire to understand her own sense of self, in response to the images and roles offered by a predominantly white-controlled media.

What does the work represent?

Sonia Boyce, From Tarzan to Rambo... detail 1987 © Sonia Boyce

Sonia Boyce From Tarzan to Rambo... 1987, detail © Sonia Boyce

In an interview with Tate curator Emma Dexter, Sonia Boyce discusses some of the works imagery and themes in detail.

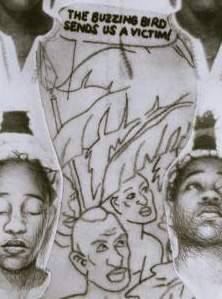

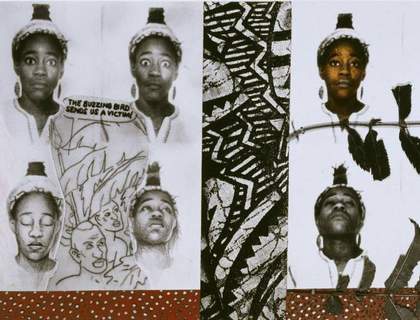

The buzzing bird

Sonia Boyce, From Tarzan to Rambo... detail 1987 © Sonia Boyce

What does the 'buzzing bird' text mean in the speech bubble added to 'From Tarzan to Rambo'?

SB: With the From Tarzan to Rambo piece, there is a speech bubble in which what look like natives say, ‘the buzzing bird sends us a victim’. The speech is complete gobbledygook, and I suppose that one of the things I’ve realized since then, is that these black characters occupy a sort of almost underworld space – they are inarticulate and any forms of articulate speech come from white characters – the main characters. And then just to talk a bit about the Tarzan figure and the so called natives in the jungle – they were taken from jungle adventure comics from the 1940’s, as a source material, to fit into these narratives and to have, in a way, some kind of relationship to photographic images of this female figure. As I mentioned before, the natives’ (I can’t think of calling it anything else I’m afraid) speech bubble makes completely no sense.

ED: So, we’ve got jungle adventure story references and somebody saying something – is that constructed to make these people appear in a certain light?

SB: That comes directly from the comic in which it was used and, in its original context, there was basically an airplane in the sky and the natives called it a buzzing bird because, of course, they had no real relationship to the modern world.

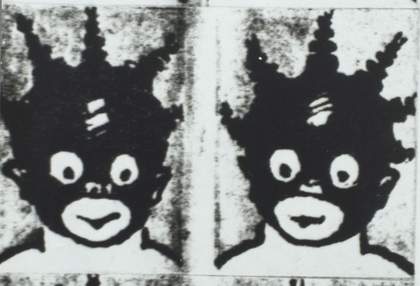

Cartoon figures

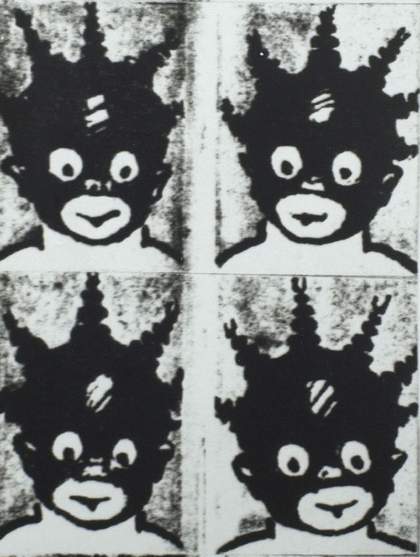

Sonia Boyce From Tarzan to Rambo... 1987, detail © Sonia Boyce

Down one side of the work, a strip of faces taken from a 1930s stereotypical cartoon of a black child frame the work...Sonia Boyce explains their significance:

SB: The figures that are in sequence on the far left are what became popularly known as golliwog figures of pickaninnies, and were taken directly from a children’s book – I’m not quite sure which one. They were common currency – that imagery was common currency – not only for me growing up as child, but before then. These images have come from the 1930’s – one doesn’t see them as readily now but I suppose they shout out a stereotype – the kind of parodying of the black body, the black figure. Again, the eyes are wide with just a dot for pupils. I’m not sure why the mouth became this almost doughnut shape, which was white but very cartoonish – very much a parody of black features. And I think there was equivalence between the supposedly benign quality of these comic children’s stories and the films. What I was doing in this piece, was to appropriate material that was already out there in a way. And its sequence as a series of six images suggests the filmic, the frame – framed on many levels really.

Tarzan - Rambo

Sonia Boyce From Tarzan to Rambo... 1987, detail © Sonia Boyce

Boyce discusses the symbolism of Tarzan and Rambo in her work:

SB: The Tarzan figure, drawn and then painted over with whites and pinks, is almost invisible – but the title suggests that Tarzan is the main figure. At the time, not just at the time of making this piece but when I was a child, I was always puzzled by Tarzan, as to why he would want to be there. It seemed like this was a choice that he had made – that he would go and live in the jungle and live with these animals and that he would become lord of that environment. And I suppose since making this piece I’ve realized that he is this kind of mythic white figure and in some way, if one looks at those 1930’s and 1940’s films which invoke the jungle, that he usurps what he believes to be the mythic qualities of the black male – being infused in some way with the beastly, and being the king of the animal kingdom.

Also, that this white figure supersedes the black male. But it has taken a long time, since making this piece, to actually understand fully what that figure might represent. At the time, it was a curiosity to me as to why this figure wanted to be in this place and I didn’t automatically assume that there was a mastering narrative.

ED: Because you could see Tarzan, in quite a stereotyped reading. As you say, as a mythic figure representing colonialist impulses and the contradictions that that also implies; because of the desire to control, dominate and master but at the same time, as well, tacit acknowledgment of the exotic, of all sorts of projected ideas about libido and other kinds of black mastery as well. Can you talk more about how you actually present the image of Tarzan – why is he being very faint, painted out?

SB: I think, because I couldn’t quite figure how he fitted in? I mean what it actually consisted of, in terms of the making of it, was drawing him in and then painting over – and as I painted to try and fill him in, he became washed out in the process. I’ve since thought about this in relation to some of the things that Richard Dyer has talked about, in terms of whiteness being everything and nothing. As an idea, it can be almost like an ethereal gas that doesn’t evaporate but is everywhere in some way, even though in the Tarzan films, his physicality is very present. And, I think, I had quite a struggle with him, as a figure in this piece – in relation to the repeated black female.

ED: So is there an element of finding that, as you were trying to draw him in, you started actually thinking ‘No I can’t do this’. Then there’s also the fact of the white male – certainly at the time that you were making this and also the cinematic time that the piece refers to – being so dominant and prevalent. Why does he even need to be seen because we know that he’s there all the time so why should he be given this sort extra bit of promotion?

SB: But the piece hinges on the title itself – hinges on his presence but not necessarily his visibility, in a way. And so he had to be there but yes, I was struggling with how, physically, he appeared there. And in fact that was the only bit of making of the piece that was a struggle. I suppose in a way, I was trying to think about the relationship between the black female within those films and also within the question of the presentation medium. Because there are points in the first set of images of her – I mean it’s repeated – where she almost disappears as well and then she becomes much stronger and more visible, as an image, in the second stage. But I think that this kind of struggle that I had was all in relation to Tarzan – in terms of their relationship to each other, within the same frame.

...

ED: So, can you then also talk about the other white male figure, referred to in the title as Rambo – because between Tarzan and Rambo, they constitute a frame that your figure almost oscillates between, in a way. So Rambo isn’t represented at all?

SB: Visually not represented but then this piece was made at the same time as the Rambo / Sylvester Stalone films had come out and he was just kind of a replica.

ED: Can you tell us a bit more about who Rambo attacks?

SB: Rambo is like a sort of guerrilla, in the political sense.

ED: Guerrilla, yes – he’s a one-man army.

SB: I mean he is part of a team, but really he works on his own and the battleground is the jungle – he goes in there with a gun and bandanna and a few bits of rags…He goes in there and he is a survivalist in that environment. I think I’ve only seen one of those films and I was shocked at the way in which Tarzan was really being re-packaged.

I think I’m still caught up with this – its bizarreness as an extremely popular narrative. Recently, over the last few months, I went back to thinking about it and did a search about Tarzan on the web, and found a huge fan base for this narrative.

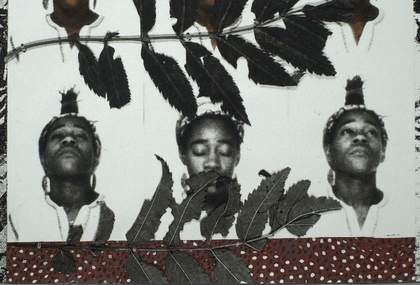

Woman's face

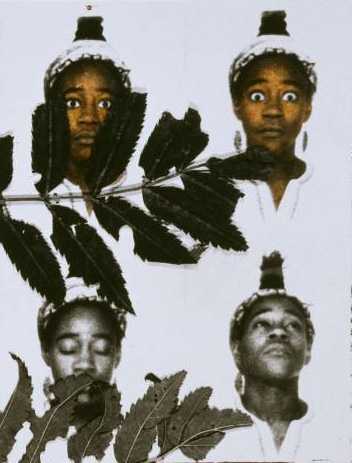

Sonia Boyce From Tarzan to Rambo... 1987, detail © Sonia Boyce

A woman's face – a self-portrait of the artist – is repeated across the artwork. Boyce discusses why she chose to include herself in this way in the work:

ED: So, Sonia can you tell us a bit about the most obvious thing in From Tarzan to Rambo – the fact that there is a woman’s face repeated on it twelve times and it’s a portrait of you – it’s your image. Can you tell us why you put yourself in the picture in that way?

SB: I suppose, what had been the starting point for me, to picture myself in this way, was thinking about films of the 1930’s and 1940’s, particularly the jungle adventure films or films where black people seemed to have been most obviously represented.

I suppose what I was thinking about at the time, was the way in which, as a child watching these films, these images became almost like a mirror in which I would see myself mimicking them – as if they were some kind of true representation of what black people were supposed to be like. And when I was making this piece, I was thinking about the irony of these representations – as being not just a model for white people to think about black people but for black people to think about themselves.

And so, the sequence of images has me looking in certain ways – in particular – there’s one image where my eyes are extremely wide open, recalling a particular actor, whose name I don’t remember, who was known, in the 1940’s, for his comic expressions of wide-eyed Negro. And then there are other symbolic gestures – of appearing to be in some form of trance – you know my head going back and my eyes closed. And in trying to think about each one of those looks as a kind of symbolic gesture, I was looking at a number of other artists who used the portrait in that way, in particular, some of the work of Susan Hiller, where she was using the photo mat / photo booth as a vehicle for creating her own image.

I was also looking at the work of Rasheed Araeen, who made a series called How to Paint A Self Portrait that seemed very in tune with what I was attempting to do – the idea of a self-portrait that isn’t a portrait at the same time, but is a kind of an ironic portrait. And the surrealists had always been crucial in my making images – I’m looking back and thinking of a group-photograph of all the male surrealists where their eyes are closed. I think this composite image was used for the cover of the surrealist magazine, where it looks as if they’re in a kind of semi-conscious state. So, I was using these three examples as a kind of model, in some way, for talking about consciousness and unconsciousness and about this sort of trance-like state – which was a favourite image of Hollywood at that time – the image of the black person as mystical in some way or as not fully conscious – under the spell of something – voodoo or something other-worldly.

How was it made?

Sonia Boyce, From Tarzan to Rambo... detail © Sonia Boyce

From Tarzan to Rambo is composed of photographs, collaged fragments, patterns and textures. Boyce has used collage techniques in previous artworks but in making this work she developed a new approach to materials and processes.

In the interview with curator Emma Dexter, she describes how she used collage, photography and drawing in the work.

SB: The question of collage was always implicit in the drawings that I’d done beforehand but I’d reached a stage where I knew that I couldn’t draw in the way that I had – you know, I’d come to a full stop in terms of making images in that kind of drawing / painterly sort of way. And so reverting to original sources and using cloth and pattern was the sort of thing I was already doing but then I brought in the things from comics and the images from film. So I suppose, I imagined myself to be doing the same sort of thing – I just wasn’t drawing any more. I was bringing these elements together but I wasn’t trying to make drawing the vehicle through which they became a piece. The photographs were done in a photo booth and I then did collage bits around it – the leaf that’s on the right-hand side was a leaf which I just sewed on and the fabric was photocopied and cut into strips. It was really a case of making a composition with various bits that were taken from various places and then the figure of Tarzan and of the natives (sorry I can’t find a better way of saying that), were literally traced from the comics and then laid on. Then, the whole piece was photographed and I worked on top of that with paint.

ED: So the whole thing is a photograph?

SB: Yes, it’s a photograph – then I painted on top of some bits of it.

ED: So, originally there’s a kind of pre-piece which you’re making, which is a collage, and then you photograph this collage. Then the large print from that was done as a sort of hand-worked piece – colouring things on top.

SB: I think what I did with the photograph before it was re-photographed – where this female figure appears – was to draw on top so there were several levels of work on top – several layers.But there was, in the final print, a point where I became really unhappy with the Tarzan figure itself, because the figure was very clear when it was first re-photographed.I didn’t feel comfortable with it so that’s where the sort of layering worked. And then I think there might have been bits where I used colour ;– but very muted colour – not strong. I was also very aware of the fact that the works I’d done before were very colourful – the pastel drawings that I’d done often required lots of layers of colouring. Knowing that I’d made a kind of break with drawing in that way, the shift to monochrome palette also took place at same time.

ED: It does also feel like a drawing at the same time. I think it’s quite interesting that it’s drawing and collage that you’ve used, one way or another, to create a piece about cinema and cinema history. So, not only have you got this almost cinema-scope, wide screen but also the use of these serial images that are very reminiscent of the way in which cinema is made up of a series of still frames. Then you’ve got those other frames which you’ve also divided up using pieces of fabric design. From that point of view, it’s quite an unusual work. One can’t really imagine many pieces which refer to another art form in such a dense sort of way, yet use very different kinds of processes and materials.

SB: I would obviously do this very differently now, given the proliferation of film and video in visual art practice. I was looking at the work of Susan Hiller who worked on top of photographs she did in photo booths – I love those works actually, because of their quality. It feels like you’re immersed in water, in some way, when you look at them or as if the film is immersed because of the marks she made on top, with water and lighting – so that they’re indecipherable but also highly readable in a way. It also makes me think of Shirin Neshat – the drawing on top of the photograph and the marking of the body was the thing that drew me to Susan’s work. Susan Hiller has talked about her relationship to the Primitive, through surrealism, so I was very intrigued by her methods of exploring that relationship.

What do the critics say?

Boyce’s work offers a reconfiguring of the iconography of race. The pickaninny that wouldn’t be out of place in Tintin’s African adventure is still there. The jungle savages of Hegel and Rice Burroughs remain. But Boyce herself is also in the frame as the subject, the architect of her own representation, no longer the object, and the victim of racial myth.

Ekow Eshun

Journalist and broadcaster Ekow Eshun shares his thoughts about From Tarzan to Rambo.

When I first saw Sonia Boyce’s piece From Tarzan to Rambo, I was aware of a faint itching somewhere at the back of my head. I knew I was trying to remember something but I couldn’t think what. Images from her work stayed in my mind: the thirties-style pickaninny child; the mohicaned savages in the bush; Boyce’s own face, by turns startled and reflective, sketched on paper and shot on film. A few days later the scratching in my head turned into what felt like a swarm of angry bees buzzing and clamouring for attention. Drawn back to the artwork I started to think about what Boyce had inscribed beneath the surface of the canvas. Two ostensibly disconnected names came to mind: Hegel and Tintin.

In 1822, towards the end of his life Hegel wrote his Lectures on the Philosophy of World History. In that work, a grand survey of the history of the world’s nationalities, he argued that Africa had never produced a culture or civilization worth speaking of. In comparison to Europe, it was a place of unredeemed barbarity and primitiveness. ‘Anyone who wishes to study the most terrible manifestations of human nature will find them in Africa. It has no history in the true sense of the word’, he concluded with a flourish, ‘we shall therefore leave Africa at this point and it need not be mentioned again’.

If there’s apparently little to unite Hegel and the plucky boy reporter created by Herge, then think of the 1931 adventure Tintin in the Congo. Here, Herge’s hero goes among the benighted savages of the Dark Continent: their skin a glistening black; their houses made of mud and thatch, their eyes liable to roll back in baffled fright at the sight of a car or a camera. Quickly he wins their trust. So much so that by the end of the book, they have come to worship him as their god, spinning legends about the great white man from Europe and even kneeling before a statue of Tintin and his dog, Snowy.

Of course, Hegel and Herge are just two random instances of how blackness, and it locus in Africa, is taken to represent little beyond savagery and simplicity. The same can be said of Edgar Rice Burroughs in whose books brutish Africans are only ever the backdrop upon which to demonstrate the blood and innate good breeding of the young Tarzan, whose name, in the local African language of the books, means White Man.

I think the buzzing in my head when I first saw From Tarzan To Rambo was a thrill of recognition. The multilayered imagery, even the acute consciousness of the sub-title English Born `Native’ Considers her Relationship to the Constructed/Self Image and her Roots in Reconstruction put me in mind of the strategies of resistance that black people have to undertake every day to avoid feeling submerged and degraded by the pervasive racism of Western culture. Boyce’s work offers a reconfiguring of the iconography of race. The pickaninny that wouldn’t be out of place in Tintin’s African adventure is still there. The jungle savages of Hegel and Rice Burroughs remain. But Boyce herself is also in the frame as the subject, the architect of her own representation, no longer the object, and the victim of racial myth.

This film file is broken and is being removed. Sorry for any inconvenience this causes.

In this film, curator Gus Casely-Hayford talks about From Tarzan to Rambo... as one of two Tate collection works that satirise nationalistic stereotypes.

What do you think?

Look at this selection of questions and prompts to help explore the ideas behind From Tarzan to Rambo.... They explore context, subject, object and the personal, and present different approaches to thinking about the work.

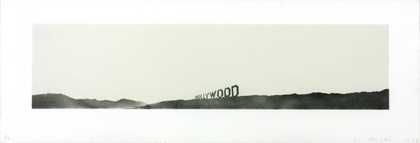

The context – hollywood and art history

Edward Ruscha

Hollywood (1969)

Tate

From Tarzan to Rambo was made in 1987, and one of its themes is the lack of a black presence within the Hollywood star system. It is also particularly about the absence of black women as positive role models. As Boyce has pointed out, despite being surrounded by black women in various states of undress Tarzan is only ever attracted to Jane, a white woman who, like himself, should not really be in this part of the world – the existence of the black women is effectively denied.

Discussion

While there has been a relatively small black presence in film for most of its history, is that still true today?

think about the following facts:

- It was only in 2002, fifteen years after Boyce made From Tarzan to Rambo, that Halle Berry became the first black actress to win an American Academy Award (Oscar), as Best Actress in a film. This is what she said:

This moment is so much bigger than me. This moment is for Dorothy Dandridge, Lena Horne, and Diahann Carroll. It’s for the women that stand beside me – Jada Pinkett, Angela Bassett and it’s for every nameless, faceless woman of colour that now has a chance because this door tonight has been opened.

- On the same night Denzel Washington became only the second black man to win the award for Best Actor, nearly forty years after the first, Sidney Poitier in 1963. In its 74 year history only five black actors (including Washington in 1990) have won the award for best supporting actor.

- Of the actresses who Berry mentioned Lena Horne was one of the few black actresses to have some degree of success during the period of the Tarzan films. In 1942 she was the first black actress to sign a long-term contract with a major Hollywood studio – MGM – in over 30 years. As part of her contract she stipulated that she would not appear in stereotypical ‘black’ roles.

The title is a good place to start thinking about the subject. It is long, and reflects the fact that behind this single work there are a large number of complex ideas. Sonia Boyce is a black artist born in England. In this work she considers herself and her self-image in relation to her ‘roots’ – her African heritage. The work was made in 1987 – at the time the Rambo films were being made – and looks back to the Tarzan films of the 1930s and 1940s.

Boyce is responding to the images of Black people in films – images she saw as a child. These ‘constructed’ images of black people – marginalised in their native habitat, while a white hero becomes ‘King of the Jungle’ – fed into her own self-image. She herself, though, is a ‘native’ of Great Britain, but through the portrayal of black people in films such as Tarzan – and of other ‘outsiders’ in more recent films such as Rambo – is made to feel an ‘outsider’ in her own country.

Discussion

We learn about people from the images that are presented of them in the media, but this is also the way in which we learn how to behave – from the examplse of others. Think about the ways in which the people are represented:

- What is the most important aspect of the work visually?

- What expressions do the photos have? What emotions do you think these represent?

- Do any of the photographic images relate to any of the drawn images in the picture?

- Who are Tarzan and Rambo? What do they have in common? Are they both represented in the image?

- Are the photographic faces more closely related to the pale image of Tarzan, to Rambo (who is not present) or the stereotype images of black people also represented?

- Is this a positive image of black people?

- How do you, or how would you feel if you were represented like this?

- Is a stereotype an adequate representation, or are there other ways of seeing people?

From Tarzan to Rambo is a large-scale black and white photographic work which the artist has worked into using drawing and painting to create different effects. It is a multi-media piece – neither a photograph, a painting nor a drawing. These different techniques are deliberately used as part of the meaning of the work.

Discussion

- What different things can you see in the image? Who or what do you think these things are?

- How are the images arranged?

- What is the connection between the faces on the left, and the ones on the right?

- What is the same, and what is different about the two sides?

- How are the faces made to look different?

- How many different ways are there to represent people in this work?

This work is about issues of race and colour, but also about image. How do we see ourselves and how are we seen by others?

Discussion

- What are your first reactions to the work?

- Why do you think or feel this way?

- Are there any images in this work which are more (or less) familiar to you than others?

- Does anything you see relate to your own personal experience, or is it about ‘someone else’?

Have a go

Inspired by how Sonia Boyce has addressed her sense of self in From Tarzan to Rambo..., here are some ways you can approach self-portraiture inspired by her work.

- Multiply an image of yourself using black and white photocopying, and use them as a base to create new identities for yourself. Draw or collage new clothes or hairstyles etc., either physically by drawing or digitally using photo editing software.

- Research images in magazines, newspapers or on the web of people expressing a variety of emotions. Take photos of yourself mimicking these expressions - if possible, select emotions you associate with. You could do this in a photo-booth, as a selfie or get a friend to shoot them.

- Choose some objects or possessions you think help define ‘you’ – photographs of your favourite people, flag colours or team logos etc. Use photography, photocopying or drawing to make 2D versions of them. Used the 2D versions to collage a symbolic ‘self-portrait’.

- What do you think people think about you? How might you be stereotyped? Can you find visual imagery to symbolise this? This can be added to work created from the above suggestions exist as a separate piece.