Public curiosity into how art is made, researched, displayed and conserved is increasing and museums around the world are moving towards opening up their collection care activities, offering more glimpses ‘behind the scenes’ for audiences to see. At Tate, collection care research projects are an important part of creating and sharing knowledge that contributes to the preservation of cultural heritage.

Tate believes in the importance of making art widely accessible and enjoyable for current and future generations, but there is still an aura of mystery around the field of conservation. Even as an intern in the Learning and Research department at Tate, much of what the Collection Care and Conservation teams do seemed strange and unfamiliar to me. With time, my experience there made things a lot clearer and I was able to grasp just how fascinating this field can be.

It was especially interesting to learn that while, at first glance, art conservation may seem to be a straightforward practice that employs long-established, foolproof methods to clean artworks and return them to their original state, the situation is actually a lot more complex. Often, conservation does not aim to reverse the effects of time, but to present an artwork as close to its originally intended appearance as possible, while respecting both the artist’s vision and the natural ageing process of objects. This can involve combining regularly updated artistic and scientific knowledge to inform aesthetic and ethical choices about how to better manage, preserve and enable access to artworks. There is no universal, all-encompassing set of clear instructions to follow, as different artworks and types of media present particular challenges to the practice of conservation.

Oil paintings are a good example of a medium widely affected by chemical and physical deterioration that takes place inside museums. With so many well-preserved oil paintings displayed in museums, one might assume such artworks are well understood and that cleaning them is relatively simple. However, there is a lot more to them than meets the eye. Some oil paintings made in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries are changing over time and many have, rather unexpectedly, become sensitive to water. This means some common conservation practices such as using a dampened cotton swab to gently clean the painting surface could remove pigment or paint. Therefore, to properly care for modern oil paintings, it has become very important to establish the causes of certain behaviours in order to understand which cleaning methods are most appropriate to care for them.

Fig.1

A Winsor & Newton Artists’ Oil Colour swatch dating to 1957, shown in tungsten and ultraviolet (UV) light. A collection of swatches was donated by ColArt UK to Tate for research purposes in 2011.

Photo by Judith Lee © Tate

This was the central purpose of a three-year collection care research project that began in 2015, called Cleaning Modern Oil Paints (CMOP). The project was carried out in collaboration with several partner organisations, each contributing specialist knowledge to answer questions around how modern oil paints were formulated and manufactured, elucidating the chemistry and physical characteristics of sensitive oil paints and paintings through analytical surveys, archival samples and over fifty works of art. Some of CMOP’s extensive findings tell interesting histories about artists’ palettes. For instance, from the nineteenth century onwards, paint manufacturers started to use different ingredients and additives to make paints chemically stable enough to be mass produced, distributed and stored. These different formulations were found to be a significant factor in causing paints to be more sensitive to water-based cleaning solutions. With that knowledge, museums are now better able to understand and respond to the behaviour of paintings in their collections.

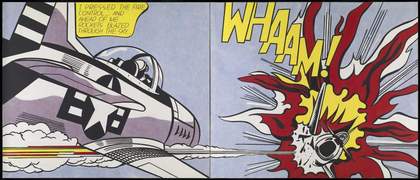

Conservators take a range of different approaches to investigating how to better care for collections. For instance, the NANORESTART project aimed to examine specific works of art in order to develop new and innovative ways to treat them. The project focused on developing a range of materials based on nanotechnologies to support the long-term protection and access to valuable works of art. Tate’s contribution to NANORESTART involved a series of in-depth investigations. As a non-expert, or outsider to the field, reading some of the project summaries felt similar to watching a crime scene investigation on television: the subject of each case study was investigated and analysed in great detail by a conservator and a team of conservation scientists, all working together to consider the work’s unique conservation needs and challenges. The selected artworks had presented conservation challenges in the past, but new technologies since introduced to the conservation toolkit made it possible to treat these pieces for the first time. In fact, one of the case studies, Roy Lichtenstein’s iconic Whaam! 1963 (fig.2), went back on display in January 2018 after successful cleaning thanks directly to cleaning methods developed as part of this project.

Fig.2

Roy Lichtenstein

Whaam! 1963

Tate T00897

© Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

Whaam! was painted with different kinds of paint, including acrylic, alkyd and oil. Although these paints look almost identical on the finished surface, they each have different chemical properties and therefore react differently to cleaning solutions. Some, like the ones studied in the CMOP project, also had particular sensitivity to water-based cleaning solutions, while others were sensitive to solvent-based systems. It was important to understand the characteristics of these materials, assess when they had been added to the artist’s palette and research how they had been applied by the artist. Fortunately, Lichtenstein described the process of creating Whaam! in detail. This information was combined with scientific analysis to recreate Whaam! as a series of test paintings. These were made, artificially aged, had artificial soil applied to them, and then tested with various cleaning options (fig.3). After choosing an appropriate cleaning system (in this case a gel made as part of the NANORESTART project called PG6), the accumulated dirt was successfully lifted from the surface of the work over the period of several months. The work was restored to its industrial appearance, a key feature of the pop art aesthetic of newness that the artist intended to present.

Fig.3

The finished mock-up panels, including (on the right) blue oil paint applied through a stencil to recreate Ben-Day dots

Photo © Tate

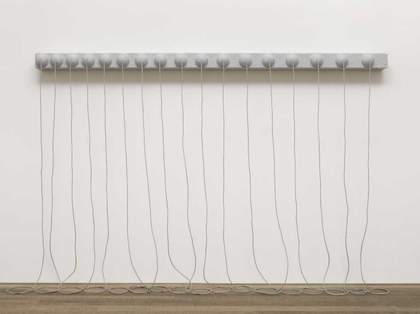

The creation of mock-ups was an important part of the conservation process for all the case studies. Whether a painting or a sculpture, mock-ups need to be as similar as possible to the artworks in treatment, both in terms of appearance and chemical composition, so that cleaning methods can be tested without risking any damage to the original pieces. For Eva Hesse’s Addendum 1967 (fig.4), the process of creating mock-ups was particularly complex because this large sculptural installation includes multiple elements in different materials, such as papier mâché, wood, paint and cord.

Fig.4

Eva Hesse

Addendum 1967

Tate T02394

© The estate of Eva Hesse, courtesy Hauser & Wirth, Zurich

It was necessary to first take tiny samples and conduct scientific analysis at Tate as well as consult specialists in Hesse’s work, including art historians, Tate curators and other museums and galleries that house the artist’s work. This was done to gain a better understanding of which materials the artist might have been using at the time and important details such as the order in which different paints and coating layers were applied to the papier mâché and ropes. Then, Tate’s NANORESTART team created a series of mock-ups imitating the topography of the original work, created from scratch by soaking newspaper in water and shaping the material to resemble the elements and surface texture of the sculpture (fig.5).

Fig.5

Newsprint being broken down into pulp

Photo © Tate

Fig.6

Grey acrylic emulsion paint was applied to hemispheres covered in papier mâché, created using bowls as moulds

Photo © Tate

These pieces were all painted with carefully chosen paints that went through colour and tone tests to achieve the exact shade of grey used by Hesse (fig.6). Finally, the mock-ups were aged in an artificial light-ageing chamber to reach the same level of degradation as the original sculpture at the time, and soiled in the same way as described for Whaam!. After extensive testing, Addendum was also cleaned with a gel produced as part of the NANORESTART project, which was designed to wrap around the ropes and remove the years of accumulated dirt. These are just a few examples of all the different strategies conservation professionals employ to research, investigate, recreate, evaluate and care for artworks.

Museums face a variety of challenges in terms of collection care and conservation, and many different approaches may be taken. CMOP and NANORESTART involved retracing past actions, retrospectively reproducing the conditions in which materials and artworks were created, as well as considering the consequences of the time that had passed since their making. The legacies of these projects will have an impact on expanding and disseminating knowledge about art, and on our experiences of viewing them. Not only do we now know how these artworks were made, but we can also use that information to conserve these and other artworks, and experience them, as closely as possible, in the way that was intended by the artists.

Imagine, then, what working collaboratively with an artist could achieve. Museums are constantly looking into new ways of doing this. Working with contemporary artworks, for instance, allows conservation to be carried out in collaboration with artists and in parallel with an artwork’s early life. Exciting initiatives such as a new research project at Tate are developing innovative models that take into account the latest technical developments within the field of conservation, as well as the social impacts of conserving artworks to make possible the sharing and wide enjoyment of cultural objects. At the heart of this initiative is a desire to open up the museum and make visible the invisible lives of these artworks as they unfold within, and in dialogue with, the museum.